Cumberland County Place Names

Cumberland County place names under the following lists: named after the founder or an early settler, geographical/geological features, and miscellaneous.

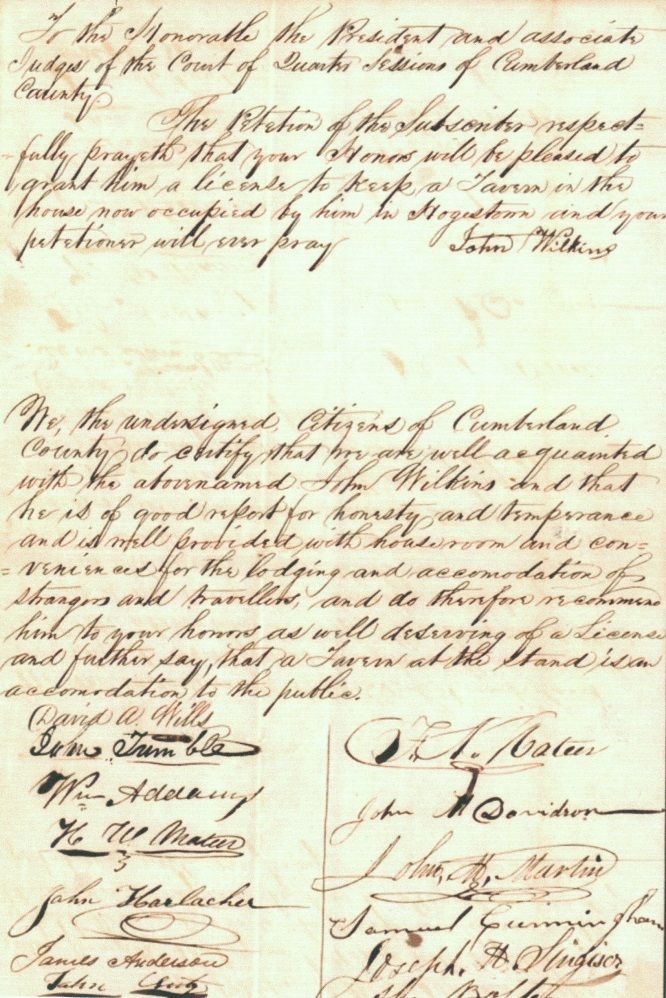

Top: John ‘Black Jack’ Wilkins’ 1844 petition to keep a tavern in Hogestown with the signatures of local men who attested to his ability to do so. Clerk of Courts, Tavern License Petition 1844.060.1-2. Cumberland County Archives.

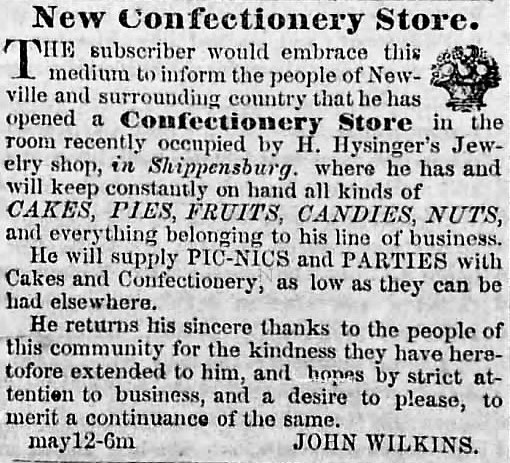

Bottom: Advertisement in The Star and Enterprise, Shippensburg, May 12, 1859.

"'Black Jack’ was a famous cook,” wrote Jeremiah Zeamer, editor of the American Volunteer newspaper. “He had a great reputation as a cook and caterer. Whenever in that part of the county there was a wedding, a dance, or a party of any kind for which a feast was to be prepared, ‘Black Jack’ was sent for to superintend the cooking and set the table, and so well did he do this that he was always in high favor with people who had appetites.”1

Born on September 1, 1805, John Wilkins was the slave of Thomas Fisher.2 Fisher operated several mills and farms in East Pennsborough Township that provided employment to many, including “colored people.” One of them, “a Wilkins, had a son named John who was afterwards long known in the neighborhood as ‘Black Jack,’ although he was a mulatto.”3

“Jack was the smartest (of Wilkins’children) and Fisher took a fancy to him, and I think, gave him some schooling…. He sent him to Harrisburg to learn the business, and I think gave him money to start with.”4 Fisher wrote his will in 1834, and he left money to Wilkins noting, “I give and bequeath to my man John Wilkins, $500. He has lived in my house all his life time. He is now in the twenty-ninth year of his age and never departed from my employment, not even for a day without liberty.”5

Frederick Breckenmaker, who boarded at Wilkins’ hotel in Hogestown in the 1840s, described John Wilkins as “a respectable man, honest and upright, decent and polite to everybody, made use of no vulgar language, and had a fairly good education. He could read and write well, was a good singer, but had a fine female voice. He was rather religiously inclined and would sometimes walk down to the Silver Spring Church…”6

Jack “first started in business in a little house which stood a little to the south of the mill and west of the bridge, but did not stay long there until he went to Hogestown.”7 “For some years (he) kept a cake and candy shop in Hogestown….His shop was a favorite place for all the youngsters in the neighborhood…” 8

“Jack’s hobby was cooking and baking, and in that he could not be excelled,” wrote Breckenmaker.

“Whenever there was an upper crust wedding about, Jack was called upon….He was famed for making big ginger cakes. He used to make a drink called mead and root beer which was fine….Why, with two glasses of that and two or three of his big ginger cakes, a man wouldn’t want anything more for the next twenty four hours. He also made the finest kind of candies. Why, on Saturday nights and Sundays he couldn’t supply the demand and whenever he was sold out—which was generally about Sunday noon---he would shut up the shop.”9

Wilkins was licensed to keep a hotel in Hogestown from 1841 through 1846.10 In the winter, “parties would come down from Carlisle,” Breckenmaker wrote.

“I saw as many as twenty five and thirty couples come. They would spend the night dancing and having a good time. All of the upper crust of Carlisle would come. They would let him know when they would come so he could prepare and did prepare. He would have the supper about midnight and I wouldn’t pretend to name half he did have, but he had everything (a) heart could wish and gotten up in first class style. It couldn’t be surpassed.”

‘“…in time Hogestown got too small for ‘Black Jack’ so he went to Newville where he did well,” wrote Breckenmaker. Wilkins was licensed to keep a hotel in Newville from 1847 through 1851. The 1850 U. S. Census of Newville records that Wilkins was a 46-year-old innkeeper, while 23-year-old Jacob Loy was his bar keeper, and 53-year-old Elizabeth Alexander was his domestic.

From Newville, Wilkins went to Shippensburg where he was licensed to keep a hotel from 1852 through 1854.11 After he quit the hotel business, he kept a boarding house. The 1860 U. S. Census of Shippensburg shows that Elizabeth Alexander was still his domestic. Seventeen-year-old Nancy Coffey was also a domestic, and there were five boarders in the house.

Wilkins died on June 30, 1860. "He was buried on Sabbath afternoon at 4 o'clock, in the Presbyterian grave-yard, and was followed to his grave by a large and respectable concourse of citizens." His obituary, in the July 5, 1860 edition of Newville's Star and Enterprise, also said that "his reputation and fame as a caterer and keeper of a public house is almost unbounded. At the time of his death, he occupied Criswell's building and was entertaining quite a number of boarders. The house is closed, and in a few weeks his household effects will be offered at Public Sale--and all that will be left of "Old Jack," will be the memory of his departed worth." The Carlisle Herald also wrote about Wilkins' death in their July 13 issue. "John Wilkins. This well known caterer for the public, died at Shippensburg on the 30th inst. aged 55 years. His death was sudden and unexpected, produced it is thought by a disease of the heart. But a few minutes previous to his death, he was kneading bread when he remarked to an elderly lady in his employ that "he felt strangely at his heart." She handed him a chair and requested him to sit down. Scarcely had he been seated, and before medical aid could reach him, he expired. Jack's proficiency in the culinary art was proverbial, as those who have been his guests at Hogestown, Newville and Shippensburg will readily admit; but his unsuspecting nature made him the prey of others, and it's probable that pecuniary difficulties aggravated the disease which carried him off so suddenly."

Cumberland County place names under the following lists: named after the founder or an early settler, geographical/geological features, and miscellaneous.

[1] “Historical Reminiscences. A letter From a Friend and the Reveries It Aroused,” American Volunteer, May 23, 1900. John Wilkins was licensed to keep a tavern in Silver Spring Township for 1841-1845. He likely leased the tavern (Hotel) and did not own it.

[2] Cumberland County Clerk of Courts. Slave and Slave Owners Register. “Record of Negros and Mulatos born after 1 November 1780.” Section 2: No. 186. Thomas Fisher of East Pennsborough Township returns and enters one male Mulatto child named John, born on the first day of September 1805. Cumberland County Archives, Carlisle, PA.

[3] American Volunteer, May 23, 1900.

[4] “More Silver Spring History,” Fred Breckenmaker, American Volunteer, June 27, 1900.

[5] Cumberland County Register of Wills, Will of Thomas Fisher, Book K-403-4. (Microfilm)

[6] American Volunteer, June 27, 1900.

[7] William Sprout in a letter to editor Jeremiah Zeamer, American Volunteer , June 12, 1900.

[8] American Volunteer, May 23, 1900.

[9]American Volunteer, June 27, 1900.

[10] Cumberland County, Clerk of Courts, Tavern License Petitions: John Wilkins 1841.055. Cumberland County Archives, Carlisle, PA.

[11] Cumberland County, Clerk of Courts, Tavern License Petitions: John Wilkins 1852.050. Cumberland County Archives, Carlisle, PA.

[12] “More Silver Spring History,” Fred Breckenmaker, American Volunteer, June 27, 1900.