Biography

Mrs. Phyllis (Krouch) Hershey was born on July 29, 1925, in Mt. Carmel, Pennsylvania. She grew up in Mt. Carmel and was graduated from Mt. Carmel High School in 1943. During the war, she worked at the Middletown Air Service Depot selling war bonds, collecting premiums for Blue Cross, and as a teletype operator. She was married in 1946 to her husband Harry R. Hershey who she met at Middletown during the war. She and her husband had a son and a daughter. After the war, she continued at Middletown and then she went to work for the Navy Depot in Mechanicsburg until 1950. She currently is widowed and lives in Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, in the house she and her husband built with war bonds they had saved working at Middletown.

Abstract

Mrs. Hershey started the interview by talking about her senior year in high school when the war broke out. The high school students participated in the war effort by patrolling the community during the blackouts and air raids and by conducting civil defense drills. She then described how after graduation she moved to Middletown with her cousin and worked at the Middletown Air Service Depot where she sold bonds and collected health insurance premiums for Blue Cross. She described her work and the wartime atmosphere at the depot which she found exciting and interesting—including a time when an airplane crashed into the cafeteria. In discussing Middletown, she described the different facilities of the base and how German prisoners of war were used to clean the depot each night. She also talked about dating at the depot. Mrs. Hershey then described her work as a teletype operator proofreading messages sent to bases around the world. She continued by discussing her life after the war with her husband, the lack of housing, their life together in a former barracks until 1949, and the challenges of daily life in the postwar years. Mrs. Hershey talked about buying their new home in 1949 with the bonds they saved during the war. She described her reaction to the end of the war and how she celebrated in Harrisburg and by restating how the depot was an exciting place for a young girl to work.

Methodology

The following transcript is based on a tape-recorded interview that is available from the library of the Cumberland County Historical Society located in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. The project’s intent in transcribing the interview was to create a clean, readable text without sacrificing the original language of the interview. Because written English differs from spoken English, the project adopted conventions to deal with the variations. No words have been added or changed, and no changes have been made in grammar or sentence structure. Words or short phrases added to clarify the text always appear in brackets; longer explanations will be placed in footnotes. Likewise, descriptions of non-verbal signs, such as nods of the head to indicate agreement or disagreement, have been

noted in brackets. In preparing the text, the transcriber omitted false starts and filler words such as “ you know” or “um.” The transcript does not include language from the interviewer that is purely procedural (such as references to turning over the tape) or language that repeats or rephrases a question. No attempt was made to preserve the dialect or pronunciation of the interviewee since the original tapes are available for those interested in those aspects of the interview. (based on the methodology used by the Wisconsin Women During World War II Oral History Project)

Jennifer Elliott: Can you tell us a little about what life was like before the war began?

Phyllis Hershey: I was in high school and it was my senior year. I hadn’t even thought of leaving my hometown or anything, but as the war went on they gave us civil service tests in high school. I passed very easily and I had planned to go into nursing, going away to school. When it came closer to the time, to graduation. I had a cousin who was working in Middletown at the air depot and her husband was in the service. She said why don’t you come down with me for the summer and work. You will have enough to go away to school. It sounded like a great idea so that’s what I did, so I went down with her. Before that in school the war was going on, all the seniors had jobs. We went out during air raids and blackouts and patrolled different things. We had a day every week [when] we would make bandages. We had to go to the tallest building in town and watch for planes. We didn’t know one plane from another; it was just kind of training. But we did all that during our last year in high school. If you went to one of the schools and there was a blackout you wore a band and you went to the school, they put you on a team and you went out to certain things. They would take you in a hearse, go some place were everyone was injured, pretend, and bandaged them up and put them in the hearse and go back to the school. I mean it was very exciting and as we graduated, so many of the boys already went into the service. They went right from school into the service. One of them was dead right before we graduated; he went in early and was in an accident in the service. He was killed; it was very scary for everybody.

Anyway after I graduated I went with my cousin down to Middletown. The next day I got a job, from then on I was working. At the time it was called a clerk typist civil service job and I got fourteen hundred and forty dollars a year. It doesn’t sound like a lot of money, but it was a lot at that time. It gave me enough money to pay my cousin rent and pay the expenses and I sent money home. I even started saving; I couldn’t believe it that I could save money. But it was pretty neat.

When I got the job, it was a day after I graduated. They took me to an office where I was going to work with a woman counselor. She was so nice, I thought she was ancient but she really wasn’t that old. Probably only in her fifties at that time, she looked older than my mother to me. But she was like another mother so it was really nice. I liked working with her and she watched out for me in all kinds of ways. I was like her receptionist, it was at the time Blue Cross was just really starting and I would collect the money for the Blue Cross. People would line up and come in this office. For one person to send up for Blue Cross was seventy-five cents a month. That’s what your hospitalized cost and for a couple it was a dollar and a half for a month. For a family it was three-fifty, for the whole family so that was pretty nice. But you see what the wages were; most people paid three months at a time. I wrote a receipt and gave it to them. They were covered, as soon as anyone was getting married she would say to them you sign up as a couple because you probably will be having a baby and you want to be covered. You don’t want to be single. We did a great thriving business in Blue Cross. Can you imagine the difference? We were in this office for a long time and then they put us in the new office and it was located in the middle of the big cafeteria. I have a picture here of it [shows picture]. In that office there was a man counselor at one end and a woman counselor on the other and they took care of the draft, anything to do with the draft. All the classifications of the guys in the service. They did the gas rationing; gas and tires, and we sold war bonds. That was my main job, be connected with these war bonds. Everybody came to work was taking out bonds like when we were in high school we were buying stamps but it wasn’t anything like that. You bought a bond, $18.75 and it was taken off your pay. When the bonds were finished being paid for, you would put [points to picture]--here it says C, D, E, F those were the bonds available and as the people came into the cafeteria for lunch. They would stop over to see if they had any bonds and they would sign this great big book and we would give them their bonds. But it was really exciting; the thing about it is we had to work shifts. We worked two weeks seven to three, two weeks three to eleven, and then eleven to seven, all night long. Every two weeks you changed shifts, you never got use to sleeping or anything. But it was a really exciting place. I saw hundreds of people every day. It was exciting. At one end of this place where you came into work there were time clocks. Where you had to punch to come into work and to punch to go out. In the evening like this, they turned all the lights out. All except where we were. Now, the restroom was right here, there were always two or three of us in here. We use to take turns; we wouldn’t walk around because it was too dark. And when it was lunchtime all the lights would come on. Everyone would rush over from where they were working and eat and check on their bonds or rationing. It was very busy. The counselors were very busy, the men and the women. Anybody that just started working would come here to sign up for bonds too. If they didn’t get all the bonds given out and we were getting them accumulated, they wouldn’t send any out with them.

They would go to different buildings to give them out. There was a very great big hanger where the planes were and that was where, to me I was eighteen it was so exciting. I was pretty impressed. You would go to the offices and they would bring the people in to sign in for their bonds. There was a parachute building where you saw how they folded the parachutes. Engine repair where they did the engines, test blocks where they tested the engines. I was thinking too there was one building, it was called a “gunk” room and they took the engines and dipped them in this stuff, not paraffin but something that preserved them. They were put on planes and sent overseas. That was the way they preserved them so they wouldn’t be damaged to be shipped out. It was a very busy and exciting place, I learned a lot.

One day we were in there and a plane, it wasn’t lunchtime but a plane crashed into the cafeteria. Into where the food was and thank goodness nobody was killed, the pilot was killed. The plane was destroyed and the pilot was killed. It would be where the airport is now, the runways and all. So there were a lot of planes coming in and going out, stuff like that.

You had said about someone on a scooter, I went home one weekend and my mother said to me, “What are you doing down there. Somebody is up here investigating you.” I said, “What do you mean?” She said, “They are going from house to house asking all about your character and everything.” I said, “Mom I didn’t do anything.” Here someone was stealing bonds and we didn’t know it. They were disappearing and they found out it was one of these girls on a scooter. When you said about this girl on a scooter, she brought the bonds down from headquarters to us; she would take a couple out. She and her boyfriend, she would take a couple from men and a couple from women, and they were cashing them. And they finally caught them, but that’s what happened.

There were a lot of scooter riders, I don’t mean just one. I couldn’t believe it that I was being investigated.

I tell you; too, in the hangers they had a lot of midgets working because they could work in the noses of the planes and stuff. There were a lot of them that worked there full time, they were so happy to have decent good jobs. They were really well paid which was a nice thing. I can’t think of what else I want to tell you right here. Do you have any questions?

JE: You answered most of them, but one question I was wondering, the people working there. Were they all from Pennsylvania, all around?

PH: They were from everywhere. There were a lot of older people that had never worked at anything. Like when I said about the gunk room where they dipped things they were all old women and men. I often wondered about the smell in there was so powerful, you wonder if they ever affected people. It was a stinky place. Well we were in there in the night, when no one was in there but us. The guards would bring in prisoners of war from Germany, German prisoners of war to clean the place. Now they had a lot of guards and these boys, they looked liked my age or younger some of them. We weren’t supposed to look at them or talk to them or have anything to do with them. And we didn’t, we couldn’t talk to them in German. They would clean all these areas, these long benches. People who didn’t eat in the cafeteria would come in and sit on those and have their lunch. That’s what they cleaned and the cafeteria and they would get them out of there. Before the shift changed and anybody came in, I never expected to see that, German prisoners of war. But like I said they looked like little kids. It was a lot of fun in one way; there was a lot of chances to date people. But you didn’t know who these people were. My counselor she showed me what to do, she said come over here and I’ll show you. If any of these wise guys want you to go out with them, look it up in here and see what their status. She said see if they are 4F, and she said or you can say what’s your name and come over here and look it up and say what about Helen and the three kids? [laughter] It was kind of neat, she taught me that. So I was very careful, I didn’t run around too much. Changing shifts, you never knew when you were going to do anything. You were sleeping a lot in the daytime, I hated that three to eleven, it seemed so confining. You got up in the morning and went to work at three and come home at eleven, you couldn’t do anything. I didn’t mind the eleven to seven and some of the girls, we would get together and go to a midnight show after the three to eleven sometimes, go to the movies in Harrisburg you could do that. Gas rationing was so bad that I hardly ever got home. I didn’t have a car and my cousin had a car but she couldn’t get gas. But if you got gas, you never had a spare tire. Because they were retreads and it was dangerous to go in these cars. It was exciting especially to be that young. I don’t know if I would have been a lot more sensible if I was older, but to me it was a big adventure. I felt it was important and I had a good opportunity.

I worked at that booth for a long time and then there were flyers that they needed help at other parts of the base. So I applied for a different job that would pay more and I got accepted and I got to be a teletype operator which was up in the headquarters building. It was in a big room in a basement of this main headquarters and along the walls were these big machines and you typed, it would be like Western Union, but it came out of a tape. The stuff came out of a tape and you had to proofread it and every hole meant a different letter or a number. You had to proofread it and you took them over and sent them in these machines to different bases in the world. It could be all over the world not only the country. Into ships at sea you sent the stuff and air bases like Wright Patterson Air Force Base and every one of these big machines represented a different place. It was really exciting and there were about five people on a shift which was one was the supervisor. If you could type you could do it but it had to be so exact. Because there was a lot to do with numbers, a lot of orders, parts of all kinds of stuff. There was an officer in a separate room there in this place and he was there to take private, secret messages, or codes. We got coded messages and gave them to him and he took care of that.

Sometimes when you weren’t working if they were so busy, they would call you and come and get you in the middle of the night. They would send a staff car and come and help because the shift was so busy. So it wasn’t the fun it had been down below, I felt that it was really important. I got more money for it but I never drank coffee before in my life but they lived on it there. I learned to drink coffee; I started out with sugar and cream, lots of it. [laughter] I got to black and I’m still drinking it black, that was exciting.

In the meantime, right before I went up there. I met this really nice fellow and we ended up getting married in about three months. I went with him and my woman counselor liked him and approved of him. She checked him out. We married in 1946, I graduated in 1943 and in 1946 I got married.

There weren’t any places to live, it was terrible. I couldn’t stay with my cousin anymore because her husband came home from the service. He was out of the service, this was a fellow that just came back from the service that I married. And we were looking for a place to live and we couldn’t find an apartment or anything. The government had housing, Marian was telling you about my housing in the barracks. I found this the other day; this is where we went to live. [shows picture of the barracks] These are old army barracks and it was in Highspire, its down next to Middletown. They aren’t there anymore; they’ve torn them down. This is an aerial view taken of it. We got two rooms in there, my mother and dad came to see us. My mother said if I made you live like this you’d cry your eyes out. [laughter] We didn’t have a private bath or anything. In the middle of these buildings would be a men’s restroom and a women’s. Four toilets, four showers and sinks and that was it. In the middle of the night, there was no privacy and you just had to go down there and that was the bathroom. It wasn’t much fun to be just married and living like this. But it was different, there weren’t any refrigerators. Everyone had an icebox, the old wooden kind of iceboxes that are so valuable now, that’s what you got. And it was furnished, it had a table and chairs and a stove. My husband, we lived in the end of this one. Right here in the middle would be the bathrooms and right where this door is was the large room and it had a phone. Nobody had a private phone, there was one phone in there and that was what you had. The boys, some of the men that were in there living knew how to fix the phone. They fixed it so that when you made a call, all your money came back. So we could call almost anywhere, but then the phone company would come and fix it again. They’d fix it back and the guys would fix it again. The kids were finding out, in the neighborhood, that this was happening that the money was coming back. So they were always chasing kids out of the place that didn’t belong there because they were after the money. What you did in this room was the beginning of tupperware; the ladies would have tupperware parties. There was nothing else; almost everybody had a tupperware party now and then. That was big recreation.

I didn’t tell you about these rooms; we had a kitchen and a bedroom and they were furnished. They had twin beds in the bedroom and you’re just married, you know. The two rooms might have been as big as this room. The walls were like paper; you could hear everything from one room to the next. They had these iceboxes; you had to let your door open everyday. If you wanted ice, we weren’t there because we were working, and they would just bring the ice and stick it in. You had to empty these pans underneath. These ingenious men got together and they came around and said, “Is this where you want your ice box?” and you said, “Yes.” And they took and put copper pipe and drilled a hole right through the floor of the building. So the water ran right under the floor so they never had to empty the pans. Isn’t that ingenious? The floors rotted, the buildings probably rotted. The water ran under the buildings, very ingenious people.

We had our names in for refrigerators and things like that, but there weren’t any. There weren’t any washers and dryers; there wasn’t nothing automatic like that. So we bought a washer, a washing machine. If you wanted to wash clothes, you had to get your washing machine down to the laundry room the night before and stick it in front of these tubs. Then get up before you went to work and do your laundry and put it out on the line. You might come home and all your clothes are on the ground because someone else wanted the line. They would just take out the pins and hang up their own stuff. It was a real cutthroat place I tell you.

Anyway, I worked there until 1950, we lived there. The main thing that we did do, he had taken out bonds all his time in the service; he was in four years in the Air Force. I had started taking out bonds from the minute that I got there. I had a lot of bonds and we met some very wonderful people. The three of us, we met two couples, and the three of us built these houses together. [In] 1949 we had bought this land, Middletown was closing, the war was over and the depot was closing. We all applied to Mechanicsburg to the Navy here and we were hired here. So we came over here and did teletype at the base here and my husband worked here, and three couples. So we bought this land and we started to build and if hadn’t been for all those bonds we wouldn’t have built we cashed the bonds, when the bricks came we paid for the bricks, and when the sand came we paid for the sand. We did this all the time that the house was being built. When we were finished we didn’t have a great big mortgage, just what we couldn’t afford to finish it. So that’s the way we did it.

When we moved in here we didn’t have any furniture because we lived in a hole in the wall. So we had a card table in the kitchen and we had a bed and that was it. And all this stuff comes a little at a time, one thing at a time. Mostly our parents’ junk and we did a lot of that over. Everything in here I have redone. Every piece of furniture all this stuff, I painted a lot of it. That was painted [points to cabinet]; it was blue when I bought it. It took three years to get it that way, to back to what it was.

[break]

We moved in here in 1949. Our daughter was born in 1950 and our son in 1956. I stopped work in 1950. My husband died in 1982—he didn’t live long after being diagnosed with liver, kidney, and pancreatic cancer. He was only 62.

JE: I only have one other question, do you remember V-E and V-J Day?

PH: Yes, we went to Harrisburg that day and it was dancing in the streets. I think we were going together then we had a great time, jumping around over there. People were everywhere, it was great. We didn’t have a car when we got married either; we ended up with an old roadster that had belonged to a veterinarian. It had extra heavy springs in it and when we moved from the barracks to this house with that little car. We did have a bed before we moved here. We were coming over the Walnut Street bridge, the one that is in half now. The mattress fell off the car, in the middle of the bridge. [laughter] We were young and dumb but we had a good time. That’s about the story of my life.

JE: Going back to when you worked at the depot, how did you and your cousin deal with rationing?

PH: Well I guess we did all right, there were only the two of us. I don’t have my ration books or anything. My mother in law was a pain in the pim, I shouldn’t say that. They always went to the shore; my parents never had any money to do anything. My husband and I went down and she said to me, “Did you bring your rationing book?” And I thought, “Oh brother!” We were only there for two days. I said to her I won’t eat any sugar stuff like this. We didn’t have any problems, there were only two of us. I don’t think it was that bad. I was a dumb cook anyway.

In the barracks the windows had no blinds or anything, you couldn’t buy anything. Paper drapes were popular so I bought a pair of paper drapes. It was just like a long closet and put a rod up there and a rod in the middle. I cut the paper drapes in half and put them here and down here and you put the pots and pans and dishes and that was it and your food. There was a stove right next to the sink and one day the windows blowing with the window open and the wind blew the paper drape over to the stove. Luckily I was standing there and I picked the rod off and stuck it in the sink. But the smoke was all over and everybody was all excited, “Is there a fire?” I put my head out and said I burnt the roast. [laughter]

And that was it, we were all young and dumb, most of us. I don’t know if anyone was dumber than us. Don’t feel as you get older that you’re different than anybody else because every generation had it. When my kids go to college, I just didn’t think they had what we went through. It was a crazy time and as I said there were no luxuries. Got a refrigerator after we got here, just whatever you could get. Things were getting better by that time.

JE: During the war did you can your food, have a victory garden at all?

PH: No, there wasn’t any place to do. Where we were, in between these buildings there was this little bit of land that’s where they put the clotheslines for you. All these buildings, this building here was an old schoolhouse. The woman who ran this whole establishment she was in there. If you wanted anything or you had any complaints you went to her. And we learned after a little while that it didn’t do any of us women any good to complain because she didn’t do anything for us. So we always sent the men and they could soft-soap her and get a new chair or something. She was much nicer to the men, she was an old bitty. She said you don’t need that if you went over and complained about something. But every building was the same; in the middle was the nucleus of bathrooms. What a mess that was, I don’t know that we didn’t get athlete’s feet or something, we didn’t get anything bad. They had someone that was suppose to clean it to but we hadn’t seen them because we were usually at work.

But this building [points to picture of the building where she use to work] was so exciting because everybody came through it. The teletype was exciting in that it was important. Seeing people everyday, hundreds of people, talking to everybody, you learned to get over your shyness. I was a stupid kid from the coal region what did I know? I didn’t think I knew anything.

JE: For your two jobs you had at the depot, what kind of training did you have for that?

PH: None.

JE: Really?

PH: No, all I had was high school.

JE: Did they train for the job when you got there?

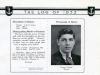

PH: There wasn’t any time. No time to train for anything, you just did it. I mean if a lot of it was common sense. When I was home I did a lot of my mother and dad’s bill paying and all that stuff. I don’t know why I was designated, I guess I was the oldest, there were only two of us. But they depended on me a great deal, I just had that kind of responsibility. I didn’t worry about not knowing and I could type very well. You know what our school did; they required everybody to take typing. Whether it was your course or not, you had to take typing. I think that was a great thing because you learned to do it. Let me show you [shows yearbook] look at these people before we graduated there’s two teachers who were in the service. These people were in the service before we got out of high school. Isn’t that something?

JE: What school did you go to?

PH: Mt. Carmel High School.

[end of interview]