Ira Shuey Eberly II – Businessman, Banker

Born on October 3, 1908, to Guy and Ada Brandt Eberly in Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, Ira Shuey Eberly II grew up around the family lumber business.

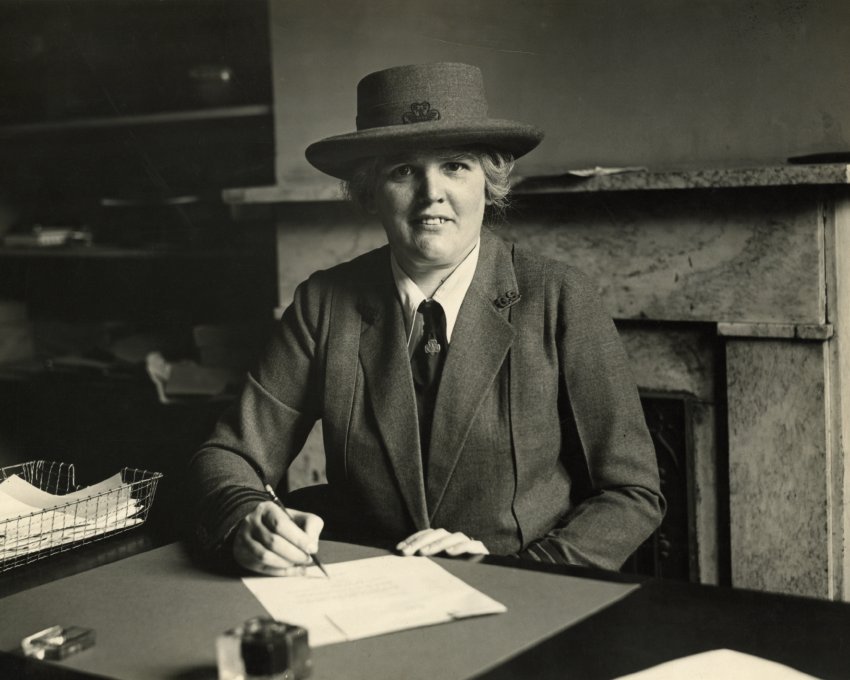

Jane Deeter Rippin in a girl scout leader uniform sitting at a desk with a fireplace behind her (CD-C-29).

Born in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, on May 30, 1882, Jane Deeter was the middle child of five and the youngest of the daughters.1 She lived in Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania with her mother while her father worked in Harrisburg, but came home on the weekends.

Later on, while her two brothers went to school, her father didn’t want to spend money on letting his daughters get an education.2 The independent woman that Jane was, she earned her B.S. from Irving College in 1902 in the town in which she lived. She became the assistant to Mechanicsburg High School’s principal after her graduation at Irving College.

Jane Deeter began her social work in 1908 at the Children’s Village in Meadowbrook, PA.3 This was a foster home and an orphanage. In Philadelphia, 1910, she was a caseworker working for the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. Jane Deeter wanted to help children so much that she instantly started to help solve problems of youth in Philadelphia. This event inspired her and five other women to systematize the Coop, her cooperative boarding house that started in 1911. Before winter, it opened to two men as auxiliary members, but their only job was to get a shovel and get the coal out of the furnace. The Coop basically turned into a crucial living facility model after some time.

Jane Deeter became Jane Deeter Rippin on October 13, 1913, when she married James Yardley Rippin.4 He was one of the first men as members of the Coop. He was a woodworker, architect, and contractor. Though surprisingly, the main income of the couple was Jane’s salary. After one year of marriage, she received an A.M. from Irving College and then landed a job as Philadelphia’s chief probation officer. Even though this job was to her pleasing, it wasn’t to her father’s. Her father definitely did not like the idea of a woman making $5,000 annually. Therefore, he forbade her from taking the job. He didn’t want to see her again, since she took the position. But, she let him in her home before he died in 1916 because of how sick he was at the time.

As part of probation work, Jane Deeter Rippin was in charge of five courts: juvenile, miscreants, domestic relations, petty criminal for unmarried mothers, as well as women’s court for sex offenders.5 Being a great politician and manager, her staff went from 3 to 365 people.

Jane had struggled with her local politicians, but in 1917, she opened a women offenders home for multipurpose municipal detention.6 It wasn’t just a basic detention home, but it included an employment agency, court, diagnostic and treatment center, and the prison had dormitories in place of cells. Being a woman, Jane knew that women and children needed specific care, so nurseries were included. Even though she also tried to add a place for women addicted to alcohol, she wasn’t allowed to do that.

The fall of 1917 was when Jane Deeter Rippin started to work with younger girls.7 The War Department’s Commission on Training Camp Activities wanted her to supervise work with girls and other women in southwest military camps. She worked to end liquor and prostitution near them. With the help of communities around her, she was able to create centers for women and girls that replaced tough delinquency methods. She was so good at what she did that she became the director in 1918 for the women and girls’ commission’s section. During her job as director, Jane Deeter Rippin worked with over 38,000 delinquent women and raised over half of a million dollars for them. To add on, she proudly sponsored the causes of delinquency study. (This even helped spark the idea and establishment of the United Service Organization USO, which was established in 1941.) In the study, she looked at girls’ organizations all over America, which started to interest her in Girl Scouts and start girls with better pursuits. Rippin was even given the role of national director for the incorporation (even while leading her own troop) until 1930. Jane made the organization started by Juliette Gordon Low into something more modern. Girl Scouts then grew from 50,000 members to 250,000 members. Everything was starting to fall into place. There were councils, training schools/camps (two that Jane’s husband designed), and more. The active promoting from her made the organization international, starting the World Association of Girl Guides and Girl Scouts (1928). The most famous part of Girl Scouts was even initiated by her, the annual Girl Scout cookie sale. Though, she only initiated it and volunteers and staff ran it.

An important achievement under her great leadership in 1926 was an International Conference at Camp Andree Clark.8 Thirty-two countries as well as fifty-six observers/delegates came from Austria, Belgium, China, Czechoslovakia, France, Luxembourg, Norway, Puerto Rico, Scotland, Sweden, Turkey, Yugoslavia, Switzerland, Canada, Costa Rica, Denmark, Egypt, Finland, England, Ireland, Japan, Hungary, Italy, Germany, the Netherlands, Latvia, Poland, Palestine, South Africa, Portugal, and Uruguay. To add on, people from almost every state in the U.S. attended. Each country brought something that resembled them to the conference. In the camp, there was a school that is still up today, which was called back then, “‘Camp Edith Macy--the University of the Woods.’”

The 1926 conference was important.9 Speakers that attended included Jane Deeter Rippin, the Baden-Powells (Sir Robert Baden-Powell being the founder of Boy Scouts), Mrs. Herbert Hoover, Juliette Gordon Low, and Dame Katherine Furse from England, who would later be the very first Director of the World Association of Girl Guides and Girl Scouts. The World Association was also proposed at the event (even though it formed two years later), and “Guide and Scout Day”/“Thinking Day” was established to bring Girl Guides and Girl Scouts into a common view. It was chosen to be on February 22, because Sir Robert Baden-Powell as well as Lady Baden-Powell shared the same date of birth, but not the year.

Even though Jane Deeter Rippin loved her work in Girl Scouts, it couldn’t last forever.10 Her health was declining and she couldn’t be the national director anymore (1930).11 But, she did stay active in the National Advisory Council for the remainder of her life. Rippin then became the women’s news director of research for Westchester County Publishers in 1931. Being a journalist, she was very good. She liked to address issues affecting women, traditional women’s affairs, women’s clubs, and garden news.

In 1936, Jane Deeter Rippin’s health really started to take a turn.12 She had her very first serious stroke and became partly paralyzed, as well as symptoms of aphasia (trouble understanding your language as far as saying it and it being on paper). But, she tried to cure her aphasia, no matter how much work it took. She successfully came over it and she wasn’t paralyzed anymore. She still continued her journalism job and being in community events until her last stroke on March 13, 1953, three months before she died in her home in Tarrytown, N.Y. Many people only think about Juliette Gordon Low when they think about Girl Scouts, but it wasn’t just her. Even though Juliette Gordon Low did start the Girl Scouts in America, Jane Deeter Rippin, native to central Pennsylvania, helped her so much through the journey and she should be remembered more today. Without her, Girl Scouts would not be as successful.

Born on October 3, 1908, to Guy and Ada Brandt Eberly in Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, Ira Shuey Eberly II grew up around the family lumber business.

[1] Sicherman, Barbara (1980). Notable American Women: The Modern Period : a Biographical Dictionary. Google Books: Harvard University Press. pp. 579–580.

[2] Sicherman, pp. 579-580.

[3] Sicherman, pp. 579-580.

[4] Sicherman, pp. 579-580.

[5] Sicherman, pp. 579-580.

[6] Sicherman, pp. 579-580.

[7] Sicherman, pp. 579-580.

[8] The Macy Story: Girl Scouts of the U.S.A. 1966, pp. 8-11.

[9] The Macy Story: Girl Scouts of the U.S.A., pp. 8-11.

[10] Sicherman, pp. 579-580.

[11] The Daily Plainsman: “National Girl Scout Executive Will Write History Organization,” July 26, 1930, pp. 7.

[12] Sicherman, pp. 579-580.