“A Klondiker’s Return. R. H. Stake, of Newburg, Brings Several Thousand Dollars Home,” headlined an item in the August 29, 1898 edition of the Carlisle Evening News.1 The newspaper reported that Mr. Stake went to the Klondike gold fields with M. Lute Arnold, former proprietor of the Mansion House Hotel in Carlisle, and another man and located paying claims about 20 miles from Dawson City. Not in the best of health, Stake returned home “with several thousand dollars worth of gold nuggets.”

In 1904, Stake moved his family to Lincoln, Nebraska. When he was 95 years old, he gave an interview to a writer from the Lincoln Star newspaper about his Klondike adventure. He would not say how much money he made, but shaking his head, he said “mighty few” got rich at it. He said that he “found a little gold, but he paid well for it.”

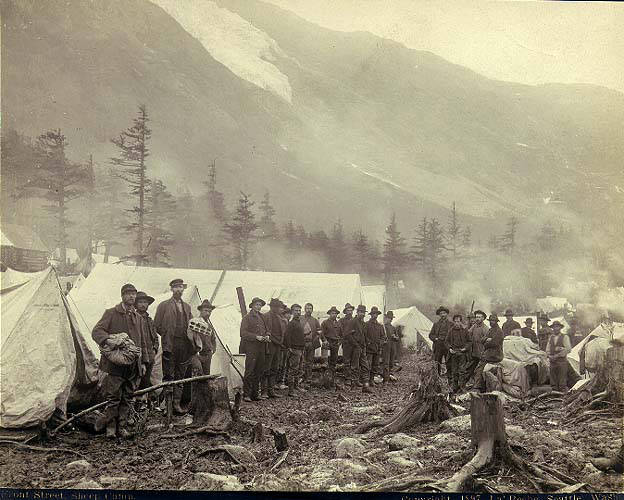

Stake was a 42-year-old storekeeper in Newburg, Cumberland County when he left his wife and children and traveled with several other men to the Klondike. They left Seattle by boat with four oxen and five tons of provisions. Quitting the boat at the infamous Chilkoot Pass, they couldn’t make the shorter but treacherous journey over the mountain with their oxen so they were forced to go around the mountain. It took several days, and the weather was cold enough “to freeze the horns off a turkey,” Stake said.

At Lake Labrage, Stake built a 30’ x 9’ boat to take them up the river to Dawson. They steered safely through the White Horse rapids and at Dawson set up housekeeping in a tent. He said he was thankful for his store of provisions so “he could make wonderful Pennsylvania pot pie” instead of paying the $1 per meal that was charged at the boarding house. Prices were so exorbitant in Dawson City that Stake once sold a 50-cent flat iron for $40.

The gold fields were a dangerous place. Men with guns ruled. Stake said that “they’d string up a man so quick he didn’t know where he was going. I’ve seen poor fellows disappear awful quick.” Stake recalled a “rough-hewn gambling place where the owner sat “high up in a corner” with two guns at hand ready to shoot anyone caught cheating or disturbing the peace.

Many men who went to the Klondike never struck it rich and never made it back home. They drowned, froze to death, were killed by outlaws or drank themselves to death. Robert H. Stake did make it home. He was annoyed that after the perils he survived in the Klondike, at the age of 95 he cut off three fingers and a thumb with an electric saw while making tulip bed stakes for his daughter-in-law. He died six months before his one-hundredth birthday and is buried in Lincoln, Nebraska.2