Brought to Carlisle from Chester County, Pennsylvania in 1772 at the age of seven,[1] Robert Darlington Guthrie would spend his adult life making silver and clocks for the residents of Cumberland County and train three of his sons to follow his profession.[2]

If Guthrie apprenticed in Carlisle, then he did so with either Samuel McMurray or William Thomson, the only silversmiths in Carlisle during the period Guthrie would have apprenticed. In 1787, Guthrie’s training was over, and he entered a partnership with George Smith.[3] Within a year they dissolved their partnership, and Guthrie advertised that he was ready for business at his location opposite Mr. Semple’s tavern on North Hanover Street.[4]

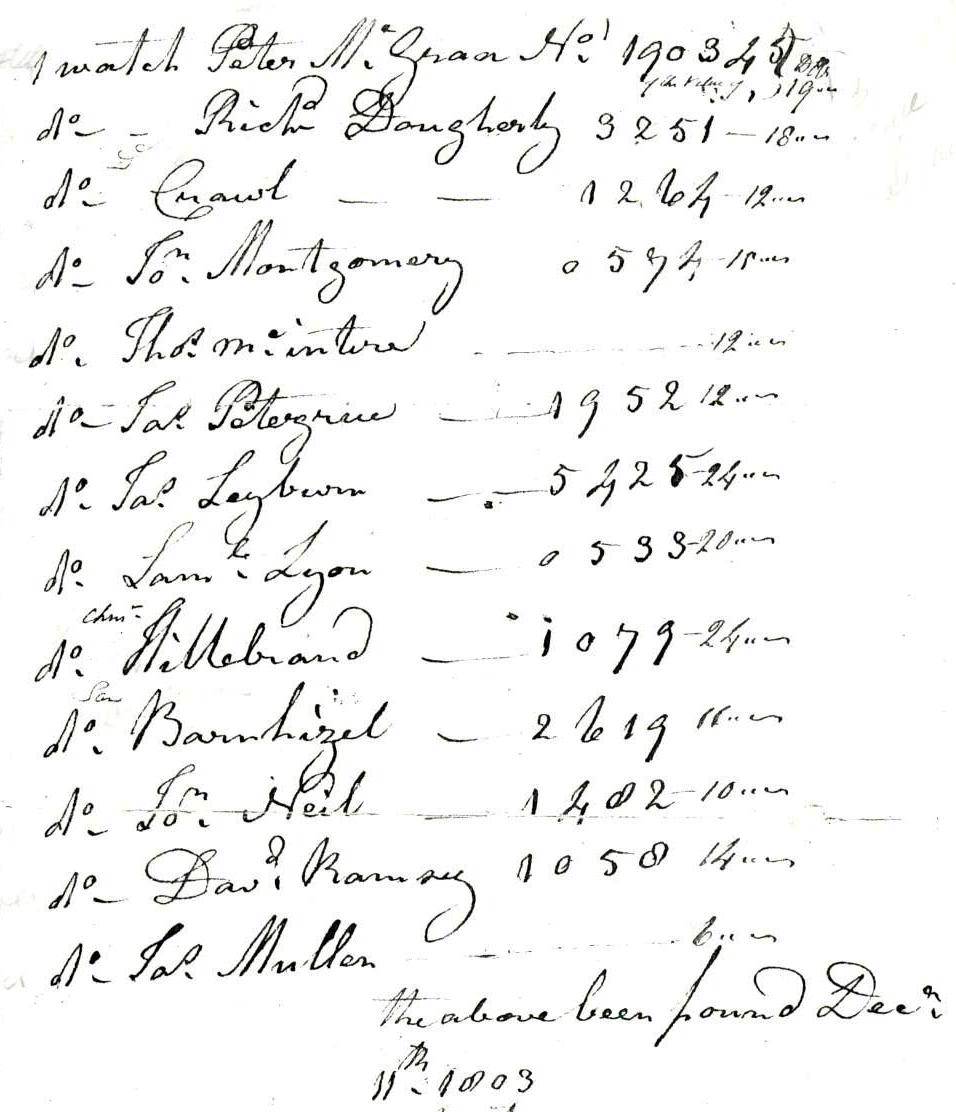

Because tall case clocks were a luxury item that only the wealthy could afford, clockmakers earned a living by making and mending silver, jewelry and other items while waiting for clock commissions. For example, Guthrie’s bill to Doctor George Stevenson in 1790 included a silver pap spoon, a set of teaspoons, repairing a spout for Mrs. Stevenson and making and engraving a pair of [shoe buckles]. [6] Guthrie was paid $7 for making a seal for the Commissioners of Cumberland County in 1800. Unfortunately, it no longer exists.[5] Silversmiths marked their items with their initials, often within an oval or a rectangle. Guthrie’s mark was R serif G in a rectangle.

Like many men, when Guthrie could not pay his debts he was sued. When that happened, the sheriff would levy goods which he held until the debts were paid, or he sold the goods to pay the debts. In July 1790, the sheriff levied Guthrie’s “household furniture and silver smith tools.”[7] In April 1792, the sheriff levied “two beds and bed clothes, six chairs, one table and one [clock].[8] In 1796, Guthrie and fellow silversmith William Thomson were sued by John Arthur, and Guthrie’s goods were levied again.[9]

Repairing watches was a large part of Guthrie’s business. In 1803, he was robbed. Guthrie testified that on “the night of the 9th inst. (December), his shop was entered, and about twelve or thirteen watches (were) stolen and carried away.” He stated that James Hopkins[10] was in and out of his shop the whole day that the watches were taken, and he believed that Hopkins stole the watches from a drawer under the bench.

Hopkins was examined and said that he “went to Robert Guthrie’s shop on Friday and cleaned (or claimed) a watch. Next, he went to George Heikes’s tavern to cut profiles for James Leyburn. He returned to Guthrie’s and stayed there a considerable time…. He went home for supper and then back to the Black Bear tavern. He went to bed there at about midnight and slept with James Charleton. The tavernkeeper said that Hopkins had slept at the tavern several times since he was married. Charleton stated that before Hopkins went to bed, he showed the company his pockets, and that he had not much money in them." Several other witnesses said that they had seen Hopkins leave the tavern several times on the night in question.[11]

We get an image of Guthrie’s storefront from a deposition taken when his neighbor was indicted for assaulting him in 1806. On March 10, Dorothy Heigel, widow of tavernkeeper William Heigel, broke and destroyed three of the front windows of Guthrie’s shop. When she broke the windows, she also broke the glasses of three silver watches that were “suspended and hanging at the front windows.” Then, she beat Guthrie with the brush that she used to break the windows.[14] The location of his shop at that time is unknown because Guthrie rented a series of houses and shops during his lifetime. In 1798, he was renting a one-story log house and a one-story log shop on North Hanover Street from Michael Miller.[15] An 1822 newspaper advertisement stated that Guthrie occupied a small frame house and log stable belonging to Andrew Scott deceased, on North Hanover Street.[16]

Guthrie died in Carlisle in November, 1840. According to his obituary, he “died in this borough on Wednesday evening last, after a short but severe illness…aged 75 years and 11 days, a native of Chester County who came here 68 years ago to reside in Carlisle.”[17]

Guthrie’s son, James, made a list of his father’s possessions at the time of his death. They included “a sideboard, a desk and book case, an eight day clock, a 30-hour-clock and case, a clock case, a stove and pipe, three bedsteads, one settee, six chairs, two cubboards [sic], two tables—one dining, a lot of books, a small dish, a lot of lumber in the cellar, a small wash stand, and one looking glass.”[18]

Addition by the author June 7, 2025. The following item appeared in the June 14, 1878 edition of the Carlisle's Valley Sentinel newspaper. "A Curiosity. By accident we were permitted to examine a fine silver medal, the handiwork of Robert D. Guthrie, a watchmaker known to the older citizens of Carlisle. The medal was presented to our townsman, Mr. Jason W. Eby, by Bishop McCoskry, then Captain of the Carlisle Light Artillery. On the medal is engraved in large letters "Captain Samuel McCoskry to Jason W. Eby, the best marksman of Carlisle light artillery. June 12, 1830." On the same side is engraved the figure of a cannon on wheels, and on the other an eagle. Capt. McCoskry is now known as Bishop McCoskry, and his name in his old age has been connected with a scandal which compelled his retirement from the church."

![Guthrie’s bill to Doctor George Stevenson for making a silver pap spoon, a set of teaspoons, repairing a spout for Mrs. Stevenson and making and engraving a pair of [shoe buckles]. Scan of Robert Guthrie’s bill to Doctor George Stevenson for various items and repairs](https://gardnerlibrary.org/sites/default/files/entry/guthrie1.jpg)