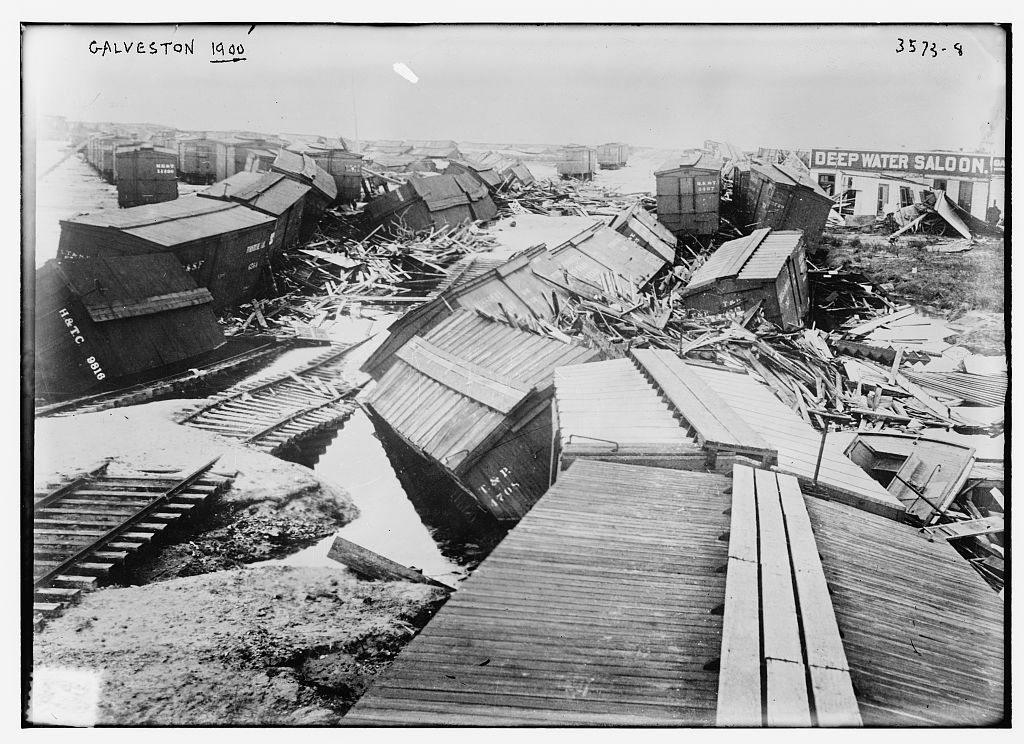

“Thousands Perish in Texas Cyclone,” “Wreck, Ruin and Death in Pathway of the Terrific Storm in Texas,” “The Greatest Catastrophe in the History of the Lone Star State,” Galveston Survivors are Totally Destitute,” were just a few of the headlines in newspapers across the United States.

On Saturday, September 8, 1900, a category four hurricane, with wind speeds calculated at 145 mph, slammed into Galveston, Texas. Galveston, situated just nine feet above sea level, was hit with a 15-foot storm surge that swept away thousands of homes, buildings and people. It was the deadliest natural disaster in the history of the United States.

A relief committee was organized in Carlisle. Its members were designated to call upon the people of Carlisle to contribute money, clothing and food for Galveston. Adam Keller, of the Carlisle Deposit Bank, was appointed the Treasurer of the Relief Fund. All cash contributions collected throughout Cumberland County were to be given to him, while contributions of food and clothing were to be taken to the 2nd floor of the Odd Fellows Building in Carlisle. The newspaper reported that the North American supply train for Galveston would be passing through Carlisle on Wednesday, September 19, and all donated goods would be loaded on the train.1

The September 19 edition of the Carlisle Evening Herald reported that “this afternoon ten barrels and a number of boxes all filled with provisions were placed aboard the North American Galveston relief car which passed through here on the 2:06 train. Burgess Vale was at the train and saw that the supplies were gotten off in good shape…Mechanicsburg gave a liberal donation.”

On September 25, Galveston issued an appeal to all Americans for aid. They reported that at least 6,000 people, about 1/6th of the town’s population, were dead. Some 2,600 houses were destroyed and 97 1/2% of the remaining houses were damaged to an estimated value of $30,000,000 (not accounting for businesses.) Approximately one million dollars would be needed to dispose of the debris along the entire length of the beach and extending three or four blocks inwards for about three miles. They reported the money that has been received has helped defray some of the cost of clearing some of the wreckage, disposing of the bodies, and seeing to the most basic sanitary needs, but when this is done, thousands will be homeless.2

The people of Carlisle and the county gave what they could. The local newspapers printed lists of the donors and the amount of cash they gave as well as clothing and food. Churches and businesses raised money. Events were also held to raise money. The Carlisle baseball team played Dickinson at their field and charged an admission fee of 15 cents, excluding the ladies.3

By October 6, a book detailing the Galveston Disaster was in J. C. Lesher’s store in Carlisle. A percentage of each book went to the Galveston Sufferers.4 As well as reading newspaper reports, townspeople heard first-hand accounts of the disaster. John D. Faller, a travelling salesman whose father Constantine lived on South Pitt street in Carlisle, had recently returned from Galveston and described the horrid conditions in a letter to his father. “Great heaps of black ashes mark the place where so many human bodies were burned,” he wrote.5

Reverend Judson B. Palmer, General Secretary of the Y. M. C. A. of Galveston, arrived in Carlisle about six weeks after the disaster to stay with his sister Mrs. J. A. Lininger. He related his ordeal to a reporter. On September 8, he had taken his wife, his child and some neighbors “to see the grandeur and fury” of the sea. They went home soon after, and Rev. Palmer went to his office. At about one o’clock his wife sent a message for him to come home. The water was rising in their house and along with some of their neighbors, they went upstairs. By seven o’clock, the front door had blown in as well as the windows. They all knelt and prayed. They thought they’d be safer in the bathroom but the roof caved in on them, and they were swept into the water. Reverend Palmer managed to grab on to a window shutter. He was then hurled onto the roof of a shed where he spent three hours while the hurricane roared around him. His wife and child disappeared and were never recovered.6