Purpose

The purpose of this narrative is to document, based on the available evidence, the approximate location of entrenchments said to have been constructed at Carlisle, Pennsylvania, during the French and Indian War.

Introduction

Colonel John Stanwix arrived in Carlisle on May 30, 1757, accompanied by a contingent of British troops. While his orders were to march to the Ohio Valley, he came to believe he was subject to a pending attack by a combined French and Indian force. As a result, he began the erection of entrenchments near the town.

In a letter written by John Armstrong on June 30, 1757, he notes, “Colonel Stanwix has begun and continues his intrenchment on the North East part of this town and just adjoining it.”1 Stanwix, writing to Pennsylvania Governor Denny on June 20, 1757, stated, “I am throwing up earthworks round our camp, and if it may have no other use, it keeps the soldiers properly employed, though I apprehend I have undertaken too much; but as it is supposed to be a camp of continuance, either now or hereafter, I could not make the line less.”2

On July 15, 1757, Stanwix wrote: “Am at work on my intrenchment, but as I send out large and frequent parties with other necessary duties, can only spare about 70 working men a day, and these have been often interrupted by frequent and violent gusts so that we make but a small figure yet, and the first month was entirely taken up in clearing the ground which was full of monstrous stumps. Have built myself a hut in camp where the Captains and I live together.3 It was during this time that Colonel John Armstrong reported he was using stones “raised out of” the works then under construction by Stanwix, to start work on a “meeting house” on the square.4

Little is known of the progress, if any, on the entrenchments, after Stanwix’s letter in late July 1757. In the Spring of 1758, Stanwix was instructed to construct a supply depot at Carlisle, capable of holding extensive supplies needed for the upcoming campaign of General Forbes. While the copy of the instructions he received is only partially readable, he was instructed to build several buildings; one 90 by 30 feet, another 30 by 40 feet, and at least one more 20 feet square. Additional soldiers were dispatched to Carlisle to provide security there. General Forbes also ordered the construction of a barracks to house the troops assigned to the town. Little is known of what was constructed, however, the site was later referred to as the “Grand Magazine at Carlisle.”5

Toussey wrote that the depot, and later the camp of General Bouquet, were located northeast of Carlisle, across the Letort Spring. He also stated that the area of the old Stanwix fort was “insufficient to contain” Bouquet’s troops. Clearly, based on this, and subsequent information, the entrenchments were not the site of the later Carlisle supply depot, although this has often been stated to be the case. The new camp at Carlisle was enlarged in 1760, and the site was used to train and deploy soldiers for several years. It was still in operation at the end of Pontiac’s Rebellion in late 1764.

It is also stated, by Toussey, that in 1769 the Colonial Government established an armory near Carlisle, to manufacture “pikes, ramrods, small ammunition, etc.” He states, in support of this statement, that recent excavations at Carlisle Barracks had uncovered several relics, including an old pike head.6 No other sources substantiate this armory.

From this information it is possible to conclude that a.) Colonel Stanwix began the construction of entrenchments just northeast of Carlisle in the Summer of 1757, b.) these works were west of the Letort Creek, and c.) the later supply depot was built east of the creek and was not on the site of the earlier entrenchments.

Locating the Entrenchments

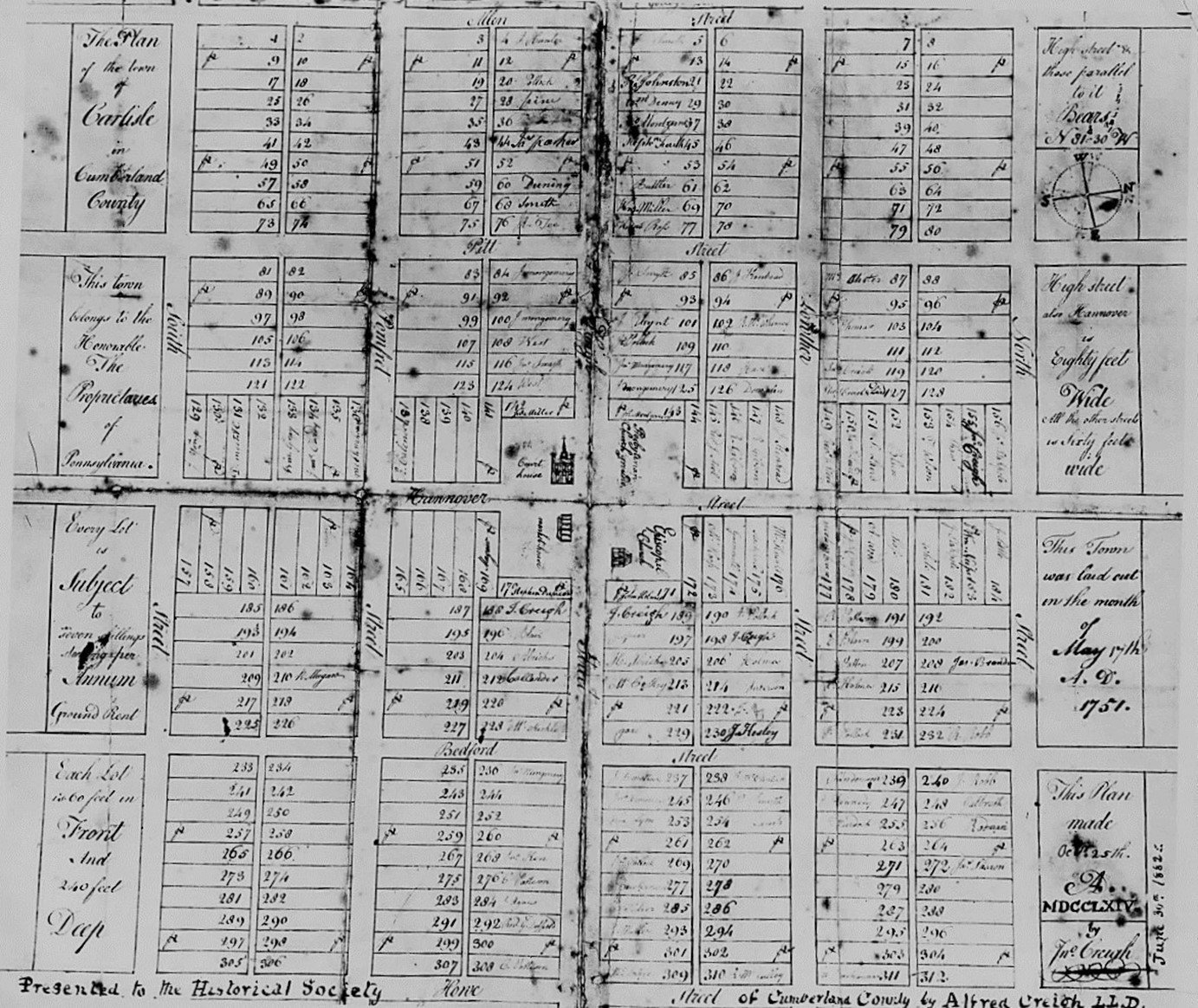

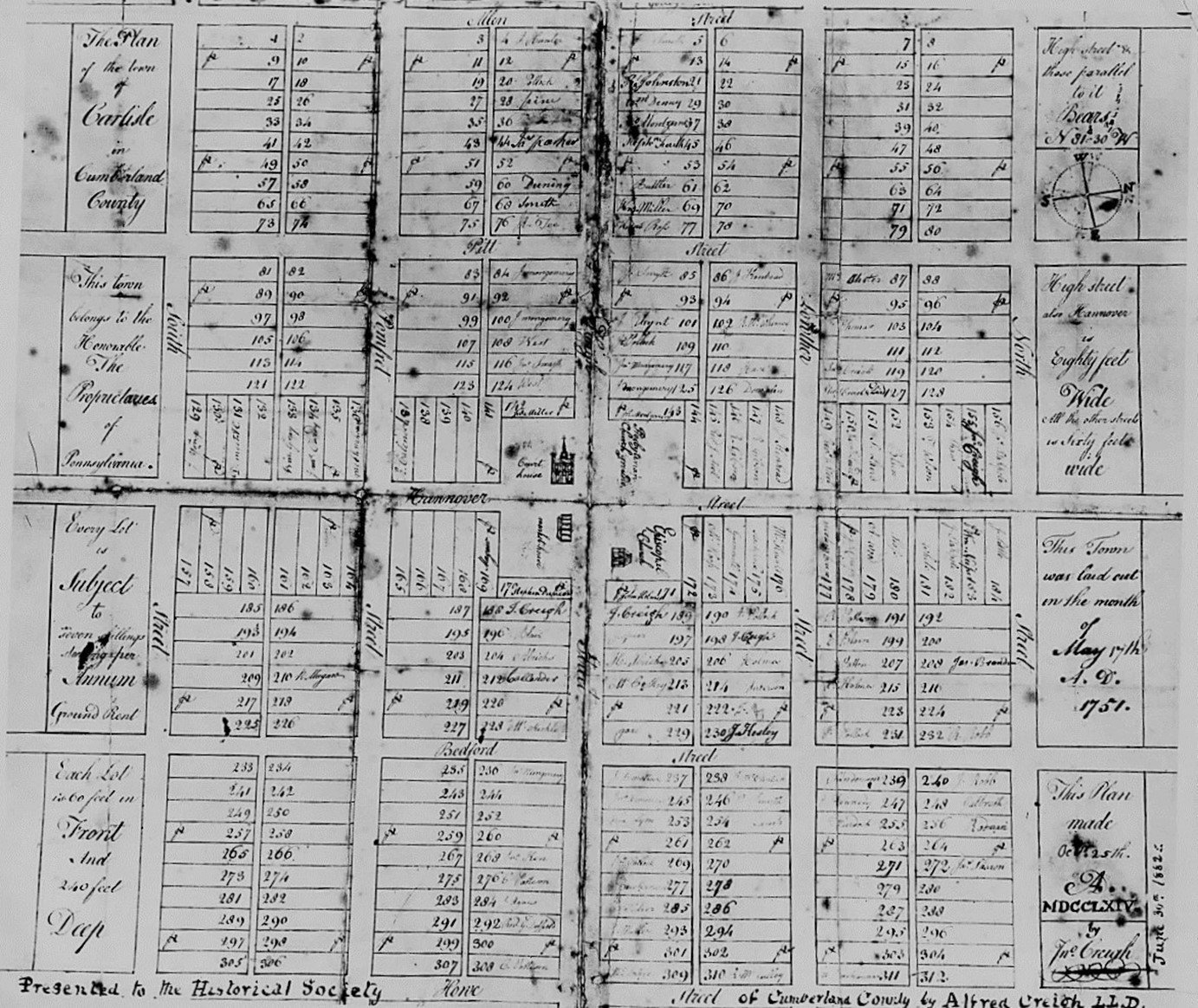

The original survey map of Carlisle, dated 1751. The “town” consisted of 16 blocks within a rectangle, 4 blocks by four blocks. The lots adjoining the town were subsequently referred to as “out lots.” As drawn, north is to the right. The Cadwalader Family Papers, Collection 1454. General Thomas Cadwalader Collection, Series 3 “Carlisle Papers” Box 1, Collection 32, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

By all accounts, both contemporary and later, the entrenchments were located “northeast” of town. Armstrong’s letter in June 1757, further states, “and just adjoining it.” If, using the compass on the draft of the town, one draws a line from the Square to the northeast, it bisects North Street almost exactly at Bedford Street. A starting assumption is that the entrenchments, by this reckoning, should be in the area of the intersection of North and Bedford Streets, or possibly adjoining the second block of North Street. It seems unlikely, based on the descriptions, that the entrenchments were east of East Street. From the early days of Carlisle, the lots east of East Street, along the Letort, were known as “Water Lots,” and were always distinguished in that manner. As no accounts of the entrenchments ever make mention of them being “water lots,” a location east of East Street can be ruled out. One account did say water was “nearby.”

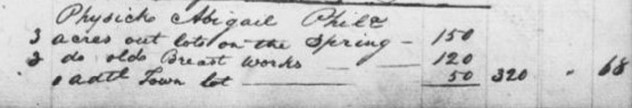

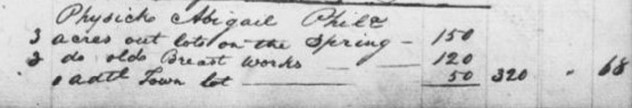

The first mention of the entrenchments, often referred to locally as “The Breastworks,” appears in the 1808 Tax Accessor’s List for Carlisle.7

This entry states that Abigail Physick (of Philadelphia) owned 3 acres of out lots on the Spring, and 2 acres (consisting of) “old breast works,” along with 1 additional town lot. The same entry appears in the 1811 Tax List.8 This further establishes that the entrenchments were not on the Letort, and that they existed and were known to the residents, or at least the assessor, of the town around 1810 – 1813.

In June 1857, the Carlisle Weekly Herald printed an article on Colonial Carlisle. It included a portion of Armstrong’s letter (referenced above) wherein he referred to hauling stone from Stanwix’s entrenchments to the Square. The Editor added the following paragraph which provides their location:

Col. Stanwix’s entrenchments, spoken of in the extract quoted above, were on the north side of the town, some remains of which existed until a few years ago, and just opposite the present residence of Andrew Kerr, Esq., occupying the ground between Bedford and East Streets, and were formerly well known as the “Breast Works.” They were commenced by Col. Stanwix in June 1757.9

The Editor of the Herald at the time was Erkuries Beatty. It is the opinion of this writer that his information is reliable.

|

|

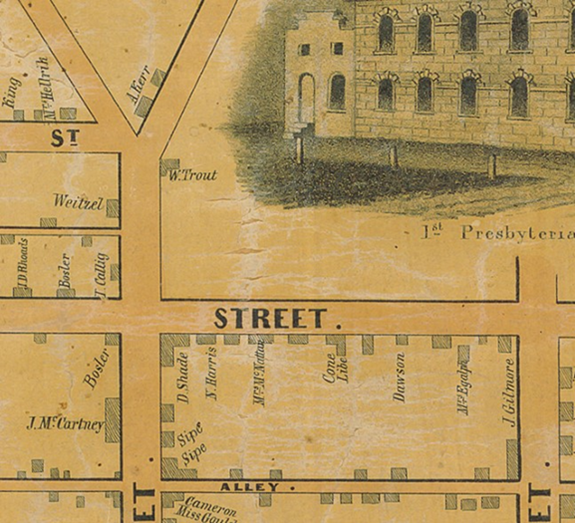

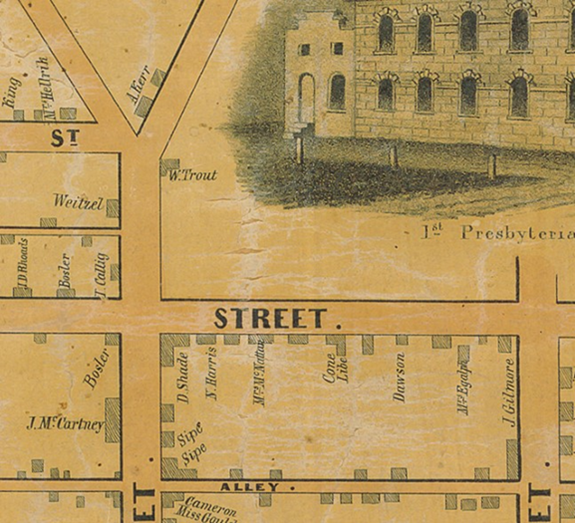

An extract from a map of Carlisle dated 1850. The residence of Andrew Kerr is circled. Bedford Street runs from the bottom to the top of the map; it curves to the right at the point formed by the intersection of Kerrs Avenue (which angles to the upper left) and Liberty (now Penn) Street, which is shown exiting to the left, perpendicular to Bedford Street. East North Street runs from left to right, a block south of the “Y.”

|

Based on Beatty’s comments the “entrenchments” were just opposite the residence of Andrew Kerr. Some additional information was provided in an August 1870 article in the American Volunteer:

The Breast Works

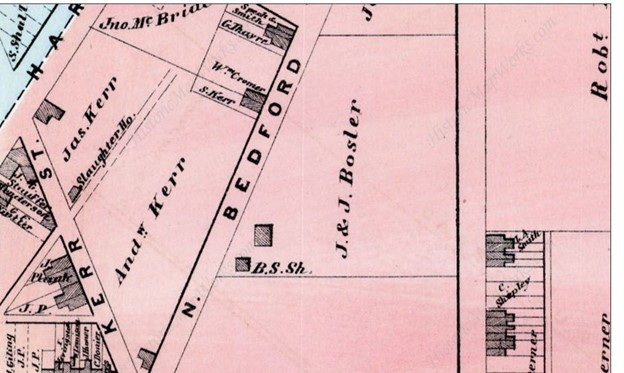

One by one the old land marks of the borough are fast disappearing, or so much altered that the “oldest inhabitant” fails to recognize them. This “Breastworks,” at the northern end of Bedford Street, thrown up in Revolutionary times as a defense against the British and Indians, has long since been leveled with the ground, and hundreds of our citizens know nothing of its site. The field whereon it was erected is now being built upon, and we see that Messrs. J. and J. Bosler have just broken ground on that historic spot, and will soon erect two brick dwelling houses, they having sometime since built upon it an extensive brick blacksmith shop. Improvements in that section of the borough are steadily on the increase, and in a short time the old breastworks lot, as well as the adjoining fields, will be dotted with dwellings, shops and business places.10

The Editor of the Volunteer at the time was John Bratton; he served in that capacity from 1848 to 1876.11 It was probably Bratton who wrote the article, and notwithstanding his errors as to when and by whom they were built, he was undoubtedly accurate in his knowledge of their location.

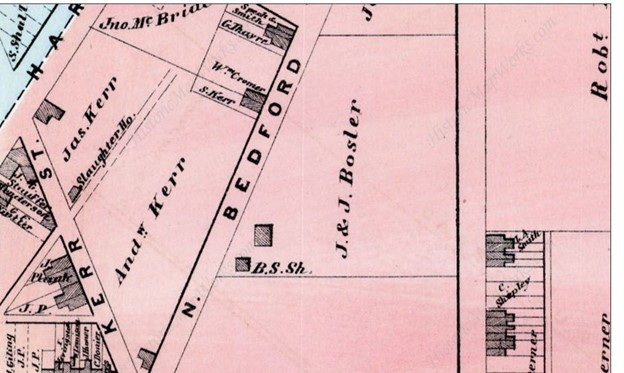

An excerpt of an 1872 map of Carlisle. The article in the Volunteer extends the possible area of the entrenchments a little further to the north. The lot to the south of the Bosler lot was owned, at the time the map was drawn, by John Moore. From what can be determined the Boslers bought the property at a Sheriff’s sale in late 1868. Present day Elm Street would pass through the square building just above the black smith shop (B. S. Sh.) and the “&” between J. & J. Bosler. The site of the entrenchments covered several acres.

For many years the subject of Stanwix’s Carlisle Camp and related entrenchments were researched by the late B. Bruce-Biggs. The following information parallels an article he wrote titled “The Camp Near Carlisle and the Carlisle Barracks; Evolution of an Error,” which appeared in Cumberland County History, Volume Thirty-three in 2016.

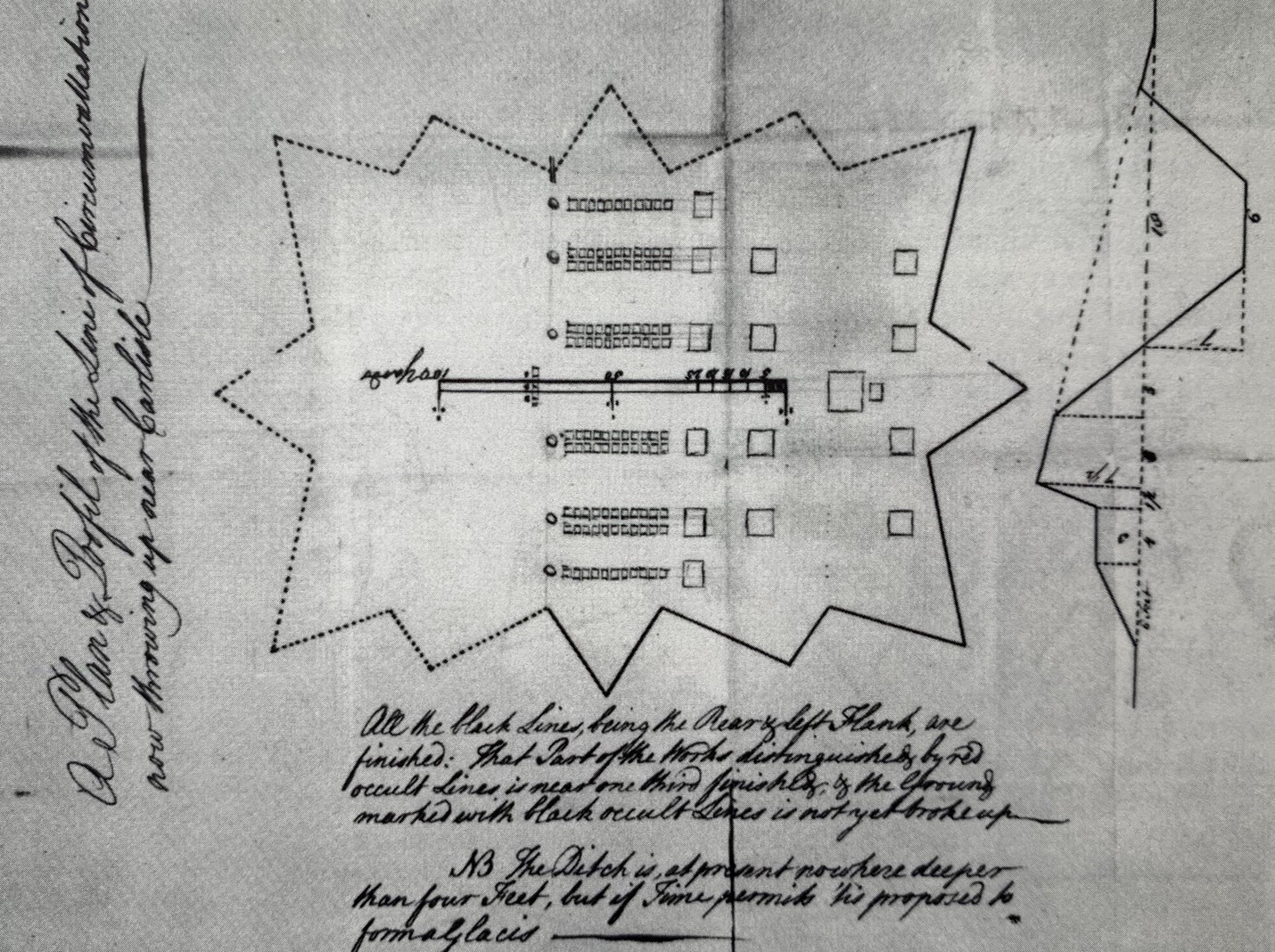

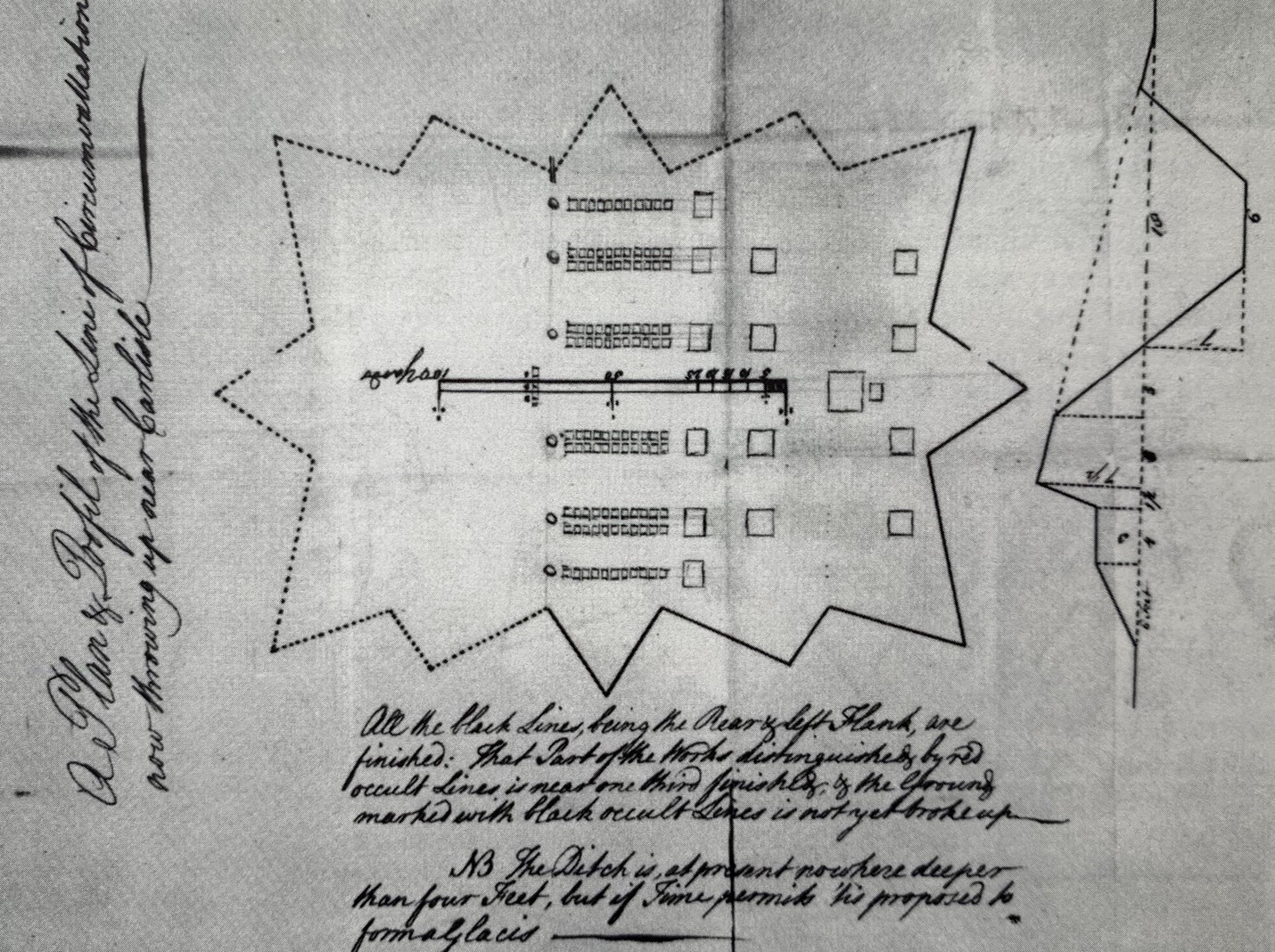

In September 1857, Stanwix wrote the following: “…in regard to our works we are throwing up here which if finished will certainly make a very useful station on the vast borders of this country, and not cost a great deal of money and will contain between a thousand and fifteen hundred men to encamp commodiously here with water very near, but what I proposed to do this campaign with the five companies was to finish what will cover the rear the right and left of our camp, which your Lordship may observe by the enclosed plan of Lt. Basset’s only penciled out.”12

The plan of Lt. Basset referred to in Stanwix’s letter above. Stotz, who wrote Outposts in the War for Empire, had access to the original sketch of Basset. He did a three-dimensional rendering of the fort and shows Carlisle to what would be the bottom of the sketch as shown, that is to say the Letort Creek is to the right, and that this sketch faces north as printed. Stotz shows the lower left corner as largely undone, while the other areas marked by dotted lines are partially complete. The break in the line at the right is a gate – likely to reach the Letort. The break in the line on the left would have faced toward Hanover Street. The sketch at the right is a cross-section of how the entrenchments would appear when complete.

The notation on Basset’s map indicates that the solid line depicts “the rear and left flank,” noting that those portions were finished. Based on this statement, and comments on the map, the “rear” faced the Letort, the “right” faced north and the “left” faced Carlisle.

It is not known if the breast works were ever completed. In October 1757, Stanwix wrote, “…in a few days I shall finish all the works I proposed this campaign and shall leave them in such a situation that Colonel Armstrong will easily preserve them. They have been a labor of five months.”13 The breast works are mentioned briefly in a 1762 report by William Eyre, an engineer from New York, who on his return from Fort Pitt, noted, “I forgot to observe there is a breastwork thrown up at Carlisle of earth, but it is now almost in ruins.”14

Bruce-Biggs estimated the length of the works at approximately 250 yards, or 750 feet. Scaling from this dimension gives a width of around 500 feet. Douglas Cubbison, in his history of the Forbes’ Expedition, gives the dimensions as 630 by 375 feet, but provides no source information.15 The overall area enclosed by the entrenchments would therefore range between 4.2 and 5.4 acres, more or less. The orientation of the map, as discussed, places the long measurement of the entrenchment roughly parallel to North Street.

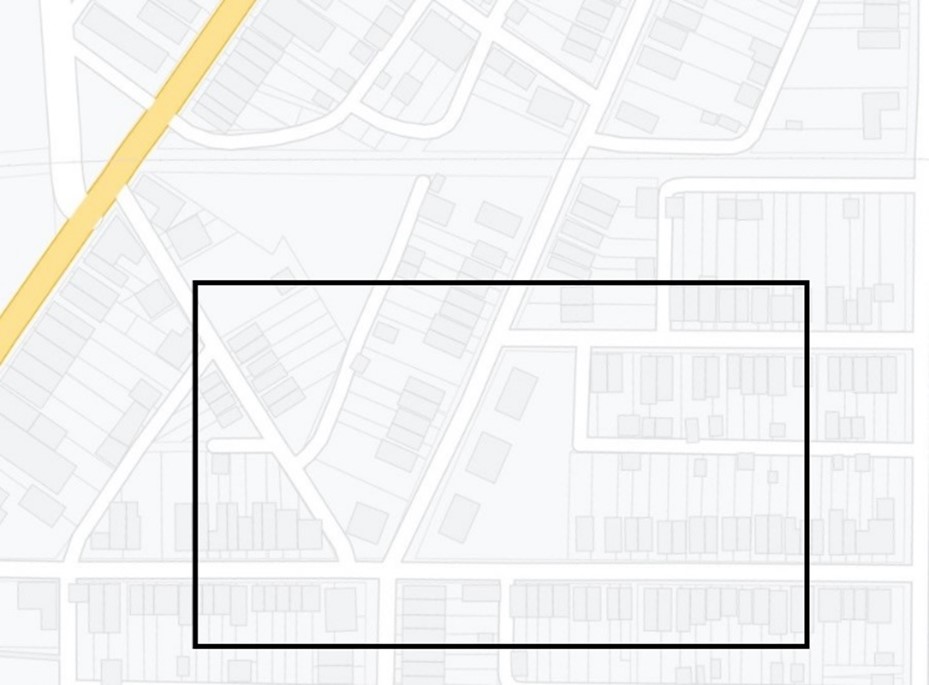

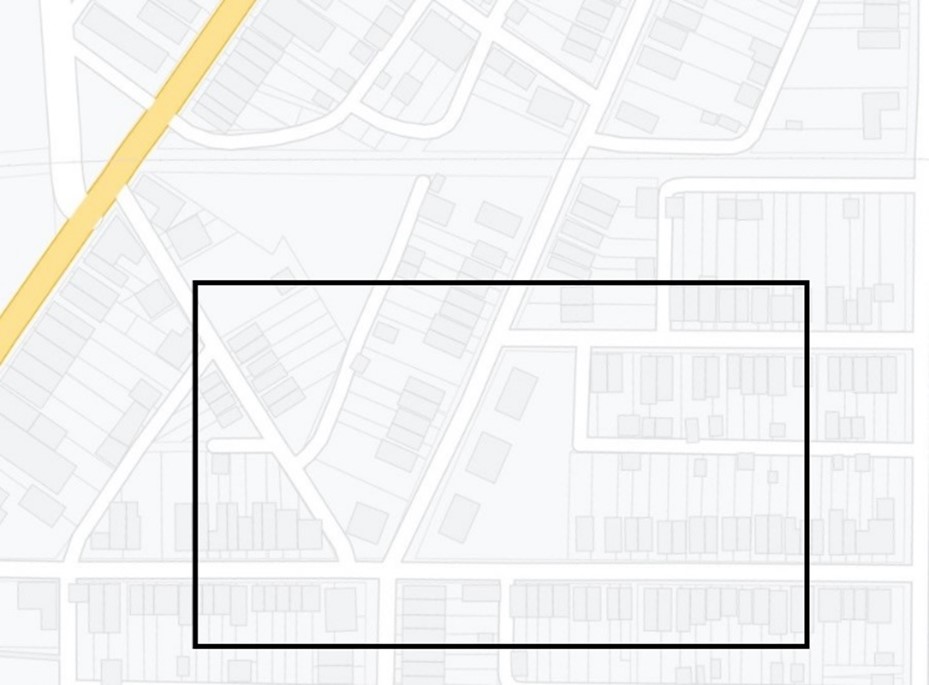

The arrow points to the area of the entrenchments along Penn Street (not all streets are shown on this map). The entrenchments were located on an elevated spur, an important consideration in their location. The elevation is still easily visible in today’s urbanized environment, it would have been very apparent in 1757. A facility along the Letort, or in the area of where the roads to Harrisburg and Croghan’s (Sterretts) Gap entered town, would have been commanded by the hill. The natural grade would have helped facilitate the construction of the entrenchments as well.

|

|

While speculative, using the stated dimensions and the descriptions from the accounts of Beatty and Bratton, matched to the topography, the approximated area of the entrenchments is shown. It seems highly probable that they fell within the marked area. The box shows the approximated size, positioned to maintain the advantage offered by elevation. Penn Street runs from left to right at the bottom; Hanover Street is shown in yellow. Bedford Street angles from the bottom center to upper right center.

|

A view of the area where the entrenchments were most likely located. This photograph shows the site of the former Carlisle Shoe factory. Penn Street leads off the right, and Bedford Street, looking north, is on the left. Note the elevation of this location. Randy Watts photo.

This view looks northwest on Kerrs Avenue. Note how the street slopes down toward North Hanover Street. Randy Watts photo.

Looking up, or west on Penn Street from North East Street. The level of Bedford Street is visible at the end of the street. The Letort Creek is 500 feet east of, and lower than this point. Descriptions of the entrenchments stated that water was “very near.” Randy Watts photo.

This view looks south from the railroad crossing on North Bedford Street. The grade ends at the intersection of Penn Street and Kerrs Avenue, where the street turns to the left. The entrenchments were most likely centered on the elevated area. Randy Watts photo.

The Andrew Kerr residence shown on the 1872 map. Tax records for Cumberland County state the house was constructed in 1841. Randy Watts photo.

Conclusion

The entrenchments constructed, or at least started, by Col. John Stanwix in 1757, were located between modern day Bedford and East Streets, with one flank, the left, approximately on the line of present-day Penn Street. By 1857, if not before, all traces of the entrenchments had been obliterated by time and human activity. Much of the surface since then has been impacted by construction. It seems doubtful more will ever be known of the entrenchments.

.

A 2017 Lidar image – the arrow points to North Bedford and Penn Streets. The Letort Creek runs from top to bottom at an angle on the right. The fill for the railroad tracks is clearly visible at the center right. There were no visible traces of the entrenchments by 1857, and the area has been heavily modified by construction since that time.

The Carlisle Shoe Company at Bedford and Penn Streets. This view looks northeast. While subtle, one can see that both Penn Street (to the right) and Bedford Street, slope down in the distance. This building was torn down in the late 1970s, and replaced with housing.