Servants played an important role in the economy of colonial and post-Revolutionary War America. Some servants were native-born, some were enslaved people, and some servants were indentured men and women who paid for their journey to America in exchange for working for a master for a predetermined period of time. They were free individuals after their contracts ended.

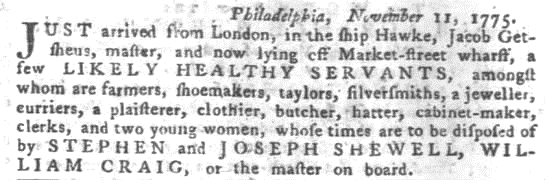

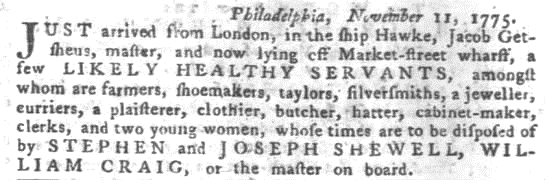

An advertisement in Philadelphia’s Pennsylvania Gazette, reported that the ship Hawke had just arrived from London and was lying off the Market Street wharf with a shipment of “a few likely healthy servants” of many different trades, “whose times are to be disposed of.” By contacting one of the men listed in the advertisement, a man could purchase the time of one or more of these servants.

The responsibilities of the master, and the restrictions put upon the indentured servant were specified in a contract which each party signed. A servant was usually forbidden to “commit fornication, nor contract matrimony,” gamble or frequent taverns during their indenture. The master was required to provide “sufficient” food, clothing, and lodging, and when the indenture was fulfilled, the servant was to receive his or her freedom clothes. Until their indentures expired, servants could be bought and sold.

Servants ran away for many reasons, and they took chances when they did. If they were caught and returned, they were punished. They had not only broken their indentures, depriving their masters of their labor, but their masters had to pay the expense of bringing the servants back from wherever they were caught. The courts added anywhere from six months to two years to their indentures in compensation to their master’s for “runaway time and expenses.”

When a runaway ended up in jail, the jail keeper advertised a description of the person and the master’s name, if known. The master was required to pay the jailer’s charges and claim the runaway within a specified length of time, or the runaway would be sold out to pay for his jail fees. In November 1776, Carlisle jailer, Samuel Postlethwaite, sent the descriptions of several runaway servants held in his jail to Philadelphia’s Pennsylvania Gazette.1 One of those was Murdock Ryley, a servant to Felix Doyle of Path Valley, Cumberland County. The jailer’s account book records that “Murtogh Riely, servant to Felix Doyle,” was admitted to jail on December 7, 1775 by John Agnew, Esq. The fees that would have to be paid by Felix Doyle, or whomever took the servant out, were a turnkey fee of five shillings, a commitment and serving fee of two shillings and six pence, and five shillings for the cost of advertising in the newspaper. Ryley spent 360 days in jail at a cost of £9. The jailer noted that Ryley was “sold out for fees” in December 1776.2

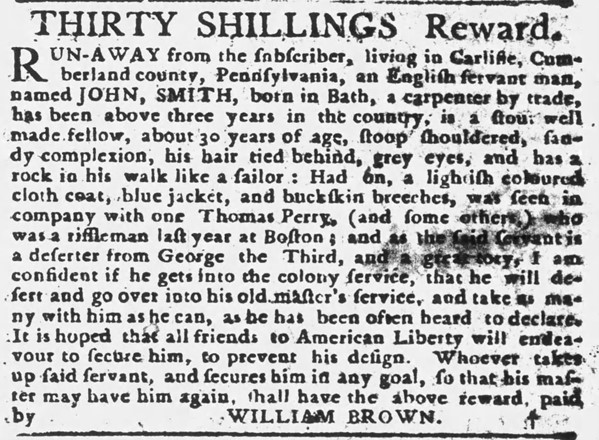

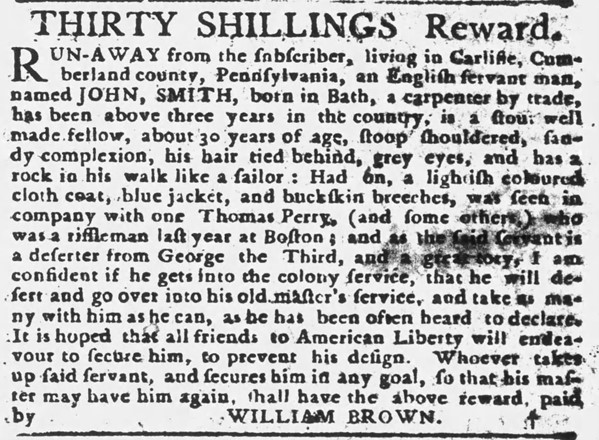

A master would provide as much information as possible to help identify a runaway when he advertised for their capture. Information about their age, height, hair color, nationality, and any distinguishing features was given. A description of their clothing was important because they were unlikely to have the means to acquire new clothes. The master also included the amount of the reward for the return of their servant.

Mary Myley and Mary Murphy, two servants who ran away from their masters in Carlisle, may have been headed for Philadelphia, but they were apprehended in April 1776 and taken to jail in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, about 60 miles from Carlisle. Mary Myley said that she was a servant of George Wright, a Carlisle tailor. “Mary Murphy, alias Judy Fegan” who had lived with tavernkeeper Christopher Vanlear and James Ramsey, both of Carlisle, was reported to be “subject to fits of falling sickness.” The Lancaster jailer, George Eberly, required the masters of the women to come and get them in the next three weeks, pay their fees, and take them away or they would be discharged by anyone paying their fees.3 Research did not uncover what happened to the women.

Harry Butler, an 18-year-old Irish servant belonging to William Kelso who operated the ferry in East Pennsborough Township, ran away in May 1776. Harry was described as “about 18 years of age, about 5 feet 5 inches high, well made to his height, has short black curled hair, a mark of a cut between his eyebrow, and two small marks on his right elbow….He is supposed to have followed his mother, who is thought to be in Captain Wilson’s company that has gone to Quebec; she advised him to run away some time before. His master offered a twenty-dollar reward for his return. As a post script, Kelso noted that the same night that his servant ran away a chest was broke open at John Harris’s [now Harrisburg]. Items of clothing were stolen, supposedly by the said servant.4

In August 1776, three servants ran away from their masters in Carlisle. Was it a coincidence that the Declaration of Independence was signed in July? One was an Englishman, and the other two were Irish.

John Smith, a carpenter by trade who was indentured to cabinetmaker William Brown of Carlisle, ran away in the second week in August. Brown offered a reward of thirty shillings to anyone who secured Smith in jail so he could be returned to his master. Brown described his servant as about thirty years of age, born in Bath, England and who came to America about three years previously. He was stoop shouldered, had a sandy complexion, wore his hair tied behind, had grey eyes and “had a rock in his walk like a sailor.” He had on a light coloured cloth coat, blue jacket, and buckskin breeches; was seen in company with Thomas Perry and others. Perry was a rifleman in 1775 at Boston. He said that his servant “was a deserter from George the Third and a great Tory,” and he was confident that if his servant “gets into the colony service that he will desert and go over to his old master’s service and take as many with him as he can, as he has been often heard to declare.” Brown hoped ‘that all friends to American liberty will endeavor to secure him to prevent his design.”5

Two servants ran away from Carlisle on Sunday morning, August 18, 1776, one a servant of George Stevenson and the other a servant of shoemaker Edmund Kean. Both men offered a reward of four dollars if the servants were taken within forty miles of Carlisle, and eight dollars if taken at a greater distance. James Hutton, George Stevenson’s servant, “was born in Ireland, but came to Philadelphia from England about two years ago.” Stevenson described him as “aged about 20 years, 5 feet 7 or 8 inches high, a slender healthy-looking lad, one eye squints, rocks as he walks, short dark brown hair which he commonly wears tied, cut short on the top of the head.” After describing the clothing he had on, Stevenson said “he can write well, and will probably forge a pass, as well for himself as for a certain William Hawthorn,” a servant of Edmund Kean who he was supposed to have run away with.6

Edmund Kean’s servant, William Hawthorn, was an Irish-born shoemaker. He was described as “full six foot high, stoop shouldered, a down look when spoken to…very talkative, and a great lover of strong drink.” He was about 25 years old “…with long black hair tied behind and the fore part of his hair turned up high…and says he formerly deserted from the Inniskillen dragoons; he also stole three pounds in cash, can write well and will probably forge a pass.”7

Catharine Lindon, an Irish servant girl ran away from Robert Darlington’s in West Pennsborough Township, in August 1776. Thought to have “been with child,” she was described as “much pock marked, a thick chunky girl, with her hair tied and almost black… She took with her one petticoat with red, white, and black stripes, one fine shift, one bed sheet, one white linen bed gown, one striped linen bed gown, half-worn shoes, and perhaps other clothes that are not yet missed.” A twenty-shilling reward, and reasonable charges were offered for anyone who secured her.8

Many runaways from Carlisle and Cumberland County were young, Irish, and never caught. Their fates are unknown, and it leaves us to wonder how their lives turned out.