Indentured servants were men and women who agreed to work for a master without pay for a specified number of years, usually in return for having their passages to America paid.

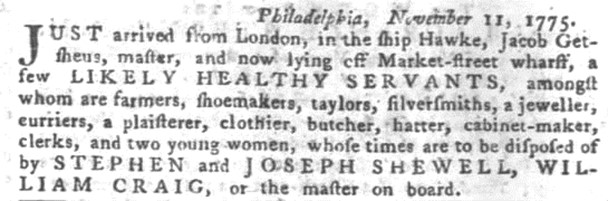

This 1775 advertisement in Philadelphia’s Pennsylvania Gazette announced that the ship Hawke had just arrived from London and was lying off the Market Street wharf with a shipment of “a few likely healthy servants” of many different trades “whose times are to be disposed of.” By contacting one of the men listed in the advertisement, a man could purchase the time of any of these servants.

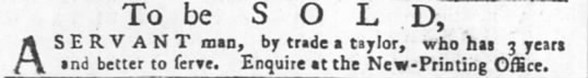

Until their indentures expired, servants could be bought and sold. As this advertisement in a Philadelphia newspaper shows, a taylor with three years left to serve was for sale.

Pennsylvania Gazette, Philadelphia, July 3, 1755

A master could sell his servant any time he wished for the value of the remaining time of the indenture. An indentured servant who only had two years left to serve was cheaper than a servant with four years to serve. It was expected that when a man bought a servant that he or she was healthy and fit for hard work. Merchant and mill owner Francis West took James Robinson of Carlisle to court in 1768 over an indentured woman whose unexpired time he had purchased in 1765. When West purchased Elizabeth Jones, he had been assured that she was a healthy servant and “free from any bodily distemper whatsoever.” West claimed that Robinson sold her to him knowing that she had distemper and convulsive fits “which wholly rendered her incapable of serving the remainder of said term, which was five years.

A record of servants and apprentices bound and assigned before Hon. John Gibson, Mayor of Philadelphia, records the names of men, women, and children who were bound out in 1772 and 1773 and to whom. The following females were recorded in April 1773 as servants to James Taylor of Shippensburg: Martha Murray, Francis More, Mary Nichols, Mary Humphreys, Sarah Frazier, Judith Conner, and Susannah Thompson.1 On May 11, 1773, William Elton assigned Mary Fitzgerald to James Taylor of Shippensburg,2 and on May 19, 1773, Mary Murphy was assigned by Alexander Cain to George Stevenson of Carlisle.3

The responsibilities of the master, and the restrictions put upon the indentured servant were specified in a contract which each party signed. A servant was usually forbidden to “commit fornication, nor contract matrimony,” gamble or frequent taverns during their indenture. The master was required to provide “sufficient” food, clothing, and lodging, and when the indenture was fulfilled, the servant was to receive his or her freedom clothes. Servants who broke the rules of their indentures were punished by the court. Rosamond Cassidy had two illegitimate children while in the service of William Miller of Carlisle. To compensate Miller for the expenses incurred, the court added one additional year to her indenture.4

Many servants ran away. In April, 1775, John Lane, an indented servant to Carlisle merchant Stephen Duncan, ran off. He was described as 5 feet 9 inches tall, about 25 years of age with a fair complexion and brown hair. He was used to driving a team, was very fond of strong liquor, and was described by Duncan as “a great rogue.” 5

Daniel M’Leane was an 18-year-old Catholic from County Down, Ireland. A butcher, indented to Abrham Loughridge of Carlisle, he ran away in November 1786. He was described as 5 feet 6 inches tall, stout-made, round-shouldered, and in-kneed.6 He must have been caught, because two weeks later Loughridge offered him for sale saying that he had about three years to serve.7 He ran away again in April 1787.8

When a runaway ended up in jail, the jail keeper advertised a description of him and his master’s name, if known. The master was required to pay the jail charges and claim the runaway within four to six weeks, or the runaway would be sold out to pay for his jail fees.

When runaway servants were caught and returned, they were punished. They had not only broken their indentures, depriving their masters of their labor, but their masters had to pay the expense of bringing the servants back from wherever they were caught. The court added anywhere from six months to two years to their indentures in compensation to their masters for “runaway time and expenses.”

Edmund Carmaddy, an indented servant belonging to William Thompson of Middleton Township, was brought before the court on April 8, 1776. He had run away on September 11, 1775, was taken up on February 3, 1776 and put in jail in Carlisle. According to the court record, his master, William Thompson, had to pay three pounds for the reward, 30 shillings to bring Carmaddy from Bladensburg, Maryland to Carlisle, 39 shillings for prison fees and food, and 12 shillings for court costs. Carmaddy’s five months of freedom cost him dearly. To compensate William Thompson, the court ordered that Carmaddy serve his master an additional two years over and above the time mentioned in his indenture.9

Although the court punished indentured servants who ran away or broke the rules of their indenture, the law protected them. They could appeal to the court for justice from masters who ill-used them or did not live up to their part of an indenture. At the October 1775 Quarter Sessions, William Clark, one of the Overseers of the Poor of West Pennsborough Township, complained to the Court on behalf of John White who had not received his freedom dues from Adam Hays. The Court ordered Hays to give John White one new coat, a new hat, and one three-year-old heifer.10

Honour Coyle took her master to court in 1775 for not upholding his obligation to her. She stated that she came to this country as a four-year servant from Ireland, and that she has served Hugh McCormick “faithfully and honestly.” She was free of her servitude since November last, but McCormick refuses to give her her freedom or what she was due by law. McCormick said that he would give her a “gown and petticoat and handkerchief,” which altogether was not worth more than 30 shillings, and only if the Court says he must. Honour said she was “friendless in the country, having none to take her part,” and prayed the court would help her.

Immigration was severely reduced during the American Revolution, and by the end of the eighteenth century, indentured servitude was dying out.