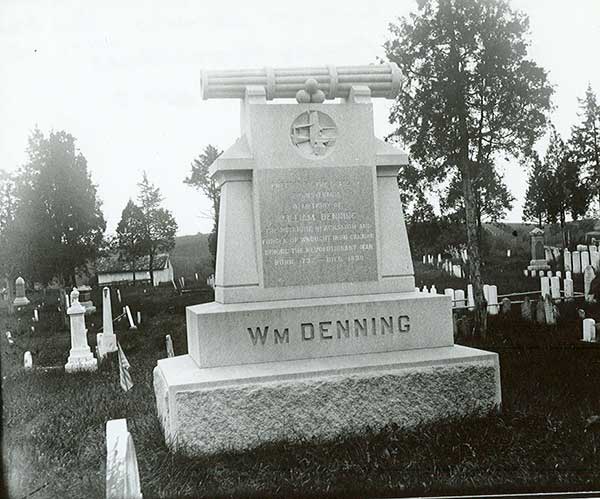

William Denning made a significant contribution to the American cause during the Revolutionary War, by creating desperately needed artillery using an unusual welding process. A blacksmith by trade, he was stationed at Washingtonburg (now Carlisle Barracks) and he welded cannons sometime between 1778 and 1780. His efforts were recognized posthumously, first in 1889 when the Pennsylvania legislature approved the sum of $1000 to create a larger, more ornate stone to mark his grave at Big Spring Presbyterian Church in Newville. And again in the early 1930s when his name was proposed for a new state recreation area being created, near Doubling Gap, that eventually became known as Colonel Denning State Park.[1]

William Denning was born in Chester County, Pennsylvania, but the year of his birth is uncertain. His obituary lists his birth date in 1736, his tombstone lists it as 1737, and a court record pertaining to his war pension puts it in 1744.[2] It was in Chester County that he learned the trade of blacksmithing, and records show he and his wife Mary owned land in Willistown Township, Chester County, prior to the war. After the Revolutionary War began he enlisted in Captain Nathaniel Irish’s company, in Colonel Benjamin Flower’s Pennsylvania line regiment of Artillery and Artificer’s. Like many other dates in William’s life, the date of his enlistment is uncertain. In a record of William’s own testimony in a court hearing concerning his pension, he says he enlisted in 1776 and served four years until 1780.[3] In his initial pension application of 1819, it is recorded he served for three years.[4] Later secondary sources have him enlisting in March of 1778 for three years.[5] His rank is also uncertain. His 1819 pension application describes him as a private, but almost all other sources describe him as a sergeant.[6] One thing is certain, he was never a colonel, that rank seems to have been assigned erroneously sometime in the 20th century.

The majority of cannons in that period were produced by pouring iron or brass into molds. Denning’s cannons were unusual because they were created with long strips of iron the length of the cannon welded together and with iron bands encircling the tube to provide added strength. Exactly where Denning worked is uncertain, but the furnaces at Washingtonburg, Boiling Springs, and Mt. Holly Springs are mentioned in several sources.[7] The cannon he produced were of a smaller size, four and six-pounders. Several sources mention his attempt to make a larger 12-pound cannon at Mt. Holly Springs, but this was unsuccessful “as he could get nobody to assist him who could stand the heat, which was so intense as to melt the lead buttons on his clothes.”[8] While Denning did not invent the process of creating welded cannons, his ingenuity and skill were a great assistance to the American cause, at a time when it was sorely needed.

After the war Denning settled in the western part of Cumberland County and resumed his trade as a blacksmith. In 1800 he was living in West Pennsboro Township in a household of eight people, a man and woman over the age of 45, presumably William and his wife Mary, and four under the age of 16, two girls and two boys.[9] It is known that he had two children who lived to adulthood, James and Mary (also known as Polly), but there is no information about any other children. James and Polly are buried with their father in the graveyard of Big Spring Presbyterian Church.10]

By 1807 William had moved to Frankford Township, and by 1820 he had settled in Dickinson Township.[11] According to his 1820 testimony in court regarding his pension, he was no longer working “owing to Rheumatic Pains,” he was living with one son and one daughter, and all his possessions were assessed at a value of $56.50.[12] It would seem that his Revolutionary War pension of $8.00 per month was much needed. He died in December of 1830, valued by his neighbors for his service during the war, but with none of the greater recognition that would come his way in the century following his death.