Although Cormick McManus, a tailor, was one of a number of Irish Catholics who immigrated to America, settled in Carlisle, and was naturalized in the early decades of the nineteenth century, he was memorable enough to be written about in the reminiscences of several Carlisle natives.

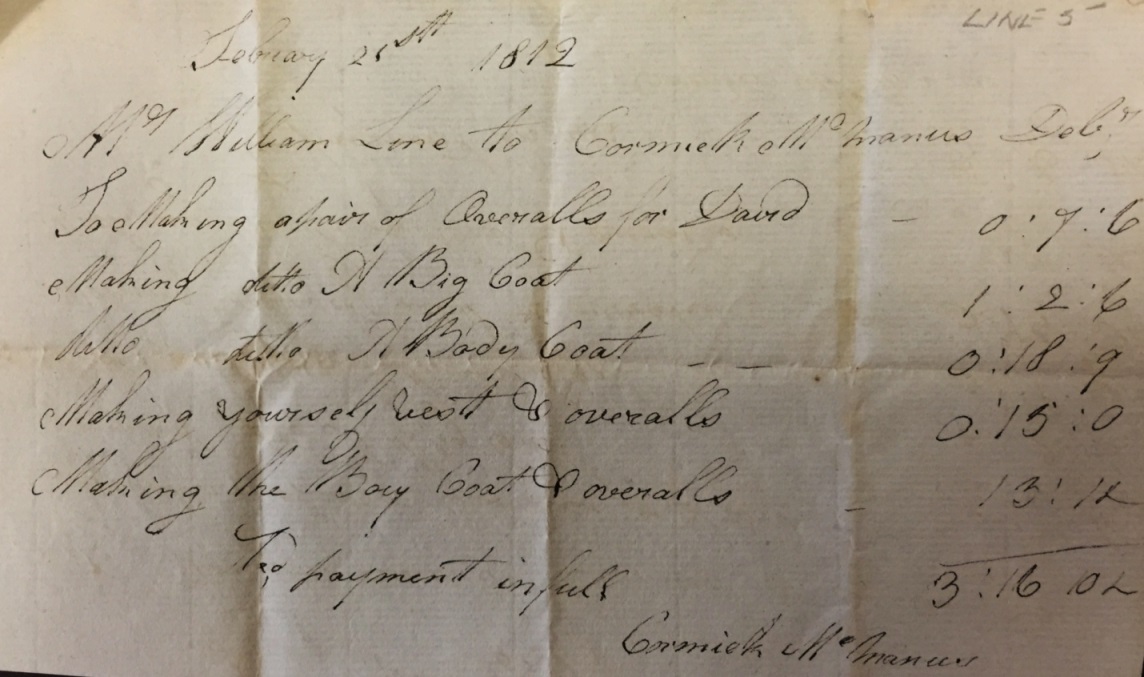

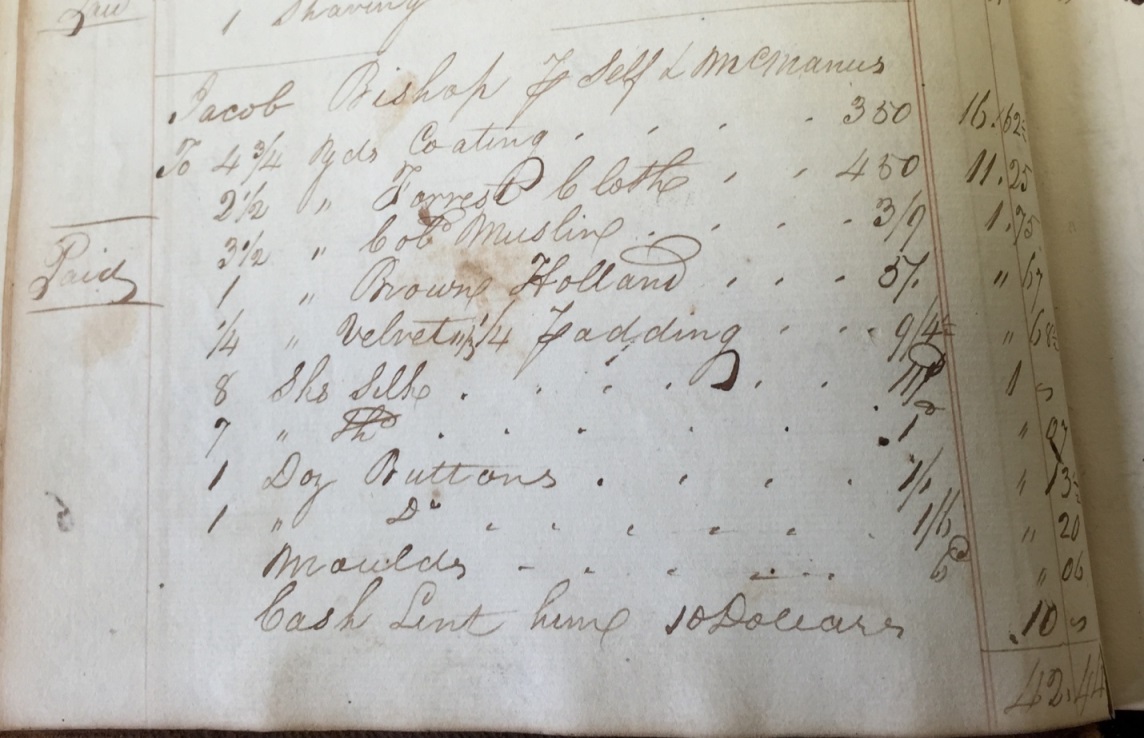

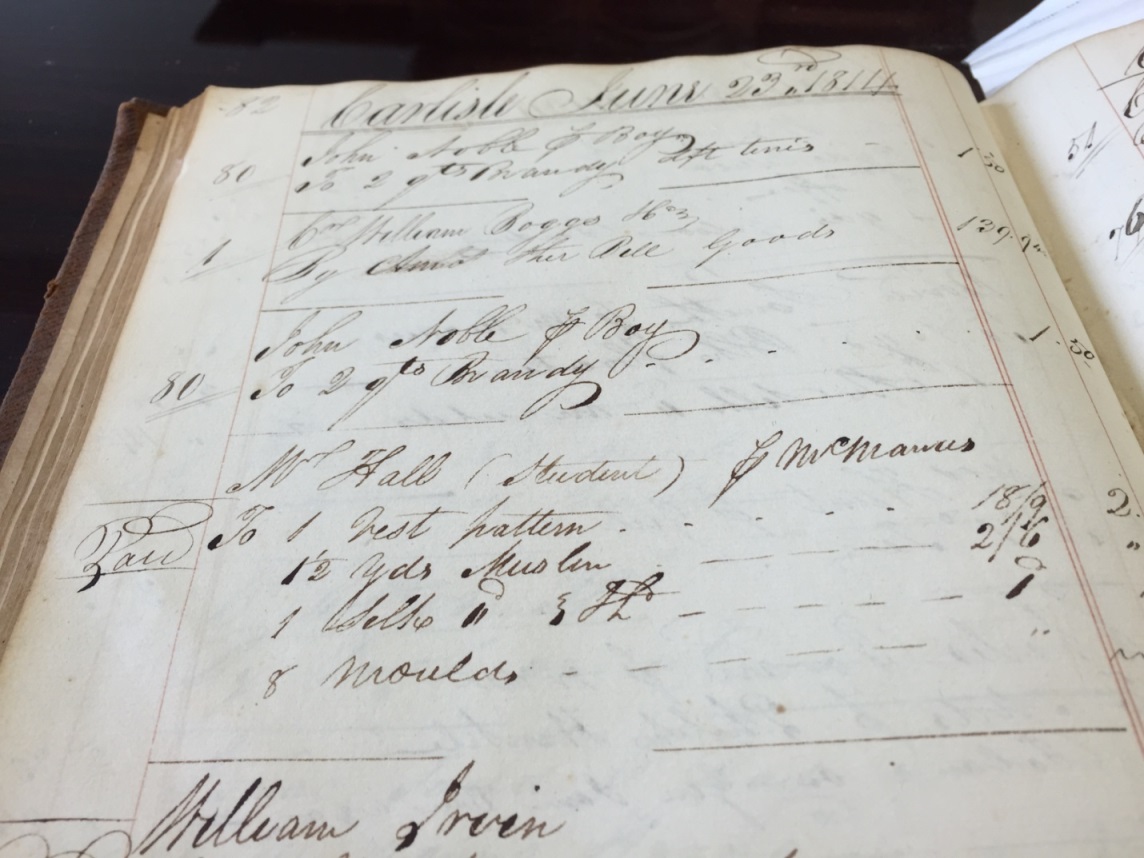

The tailor shop of Cormick McManus on West High Street, wrote James Miller McKim, was:

“a small frame tenement, remarkable for nothing except the man who occupied it; who was no ordinary person either, professionally or as a man and citizen. In fact, Mr. McManus was a good deal above the average of his contemporaries, both in mechanical skill and general intelligence. As a tailor, he was to Carlisle what Watson was at that time in Philadelphia; and although a few of our exquisites used to boast that they wore nothing that was not made by Watson, the great majority of the well-dressed people of this place were indebted to their presentable appearance to the artistic shears of Mr. Cormick McManus. He was a facetious man in his way, and his bon mots used to be much quoted by his customers, as for instance, “He had got down to be a lawyer” as he said when his eldest son left the bench for the bar! “She is not deadly beautiful, but she’s killing genteel,” as McManus said of a well-known lady.”[1]

Another Carlisle native, reminiscing about the people on West High Street wrote: “The lot adjoining the Commodore Elliott lot on the east had on it two frame houses. One of these was occupied by Cormick McManus, who was an excellent tailor and a man of most polished manners…He was a pious Catholic and is buried in the graveyard of the Catholic Church.”[2]

McManus was one of the Trustees of St. Patrick’s when the church was expanded in the early 1820s. A very public scandal was played out in the local newspapers by the builder, Barney Carney, and the church’s Trustees. Fortunately, through the efforts of “Father Dwen and the conciliatory action of the old Trustees, headed by the prudent Cormick McManus, a calamity which might have resulted in irreparable spiritual harm…” was averted.[3]

The congregation of St. Patrick’s were supportive of Daniel O’Connell’s fight for Catholic Emancipation in Ireland in the 1820s. The New Catholic Association was created in Ireland in 1828 to promote Irish commerce, manufacturing, agriculture, education and religion, and also to promote universal emancipation. “Carlisle was one of the first inland towns to take the initiative in joining the Catholic Association.”[4] From February to March 14, 1828, $100 was raised in Carlisle for the New Catholic Association. The money was sent, and the names of the Carlisle contributors, including that of Cormick McManus, were printed in Dublin’s Weekly Register.[5]

In April 1816, McManus had purchased the eastern half of Lot #284 on East High Street; a house his heirs lived in until the 1880s.[6] James W. Sullivan, a native of the east end of Carlisle, wrote about his old neighbors, the McManus family.

“…The McManus house is rich in suggestions for my chronicles. Of the three daughters there, Mary married in the 1830s Michael Egolf, brother of “Miss Barbara,” who so long had a famously good boarding house in Hanover Street. She told me she once started to write a history of Carlisle, had bunches of notes on the subject; she quoted to me some of them. Who has this precious mine of facts? Was this matter ever published? During the Civil War, Mrs. Michael Egolf brought to Carlisle from Brooklyn—and to this McManus home, six of her children-Margaret (several years later to become Mrs. Joseph Cornman), Minnie, Lily, Edward, Ernst (who enlisted in the Regular Army) and James. Three boys beside were then in the Army of the Potomac, in the Brooklyn Fourteenth Regiment. At Gettysburg two of them were killed; their bodies were brought to Carlisle and buried in the Old Graveyard. Their graves, marked by government headstones, are in the southern part, midway from South street. The third, Lieutenant Jack Egolf lost a leg in the same battle. He spent several months with his mother and the other survivors of the family during his convalescence--a gallant young soldier, whose high spirit braved misfortune. Nearly all this family still living returned to Brooklyn before the close of the war. They were interesting people, lively, intelligent, sociable.

Of the three McManus brothers, (sons of Cormick) John was long a Centre County teacher; James a Bellefonte lawyer who lived to become the Dean of the Centre County bar….The last of his three daughters, Margaret, is “in her nineties.” Will, a son, was a West Point man.”[7]

Cormick McManus wrote his will in 1840, two months before his death. He willed his house and half lot on East High Street to his daughters Frances and Margaret as long as they remained unmarried. (They were still living in the house in the 1870s.) He also mentioned his sons James and John and his daughter Mary, the wife of Michael Egolf.[8]

Cormick McManus died on September 17, 1840, aged 61 years. His obituary stated that he died of dropsy “and for the last 36 years [was] a highly respected citizen of this borough.”[9] He is buried next to his wife Margaret who died on July 7, 1817 at the age of 37 years. They are both buried in the grave yard at Patrick’s Church.