Sleighing Parties: February 1911

Young people eagerly anticipated sleighing parties. Once enough snow had fallen, and a destination was established, horses and sleighs were commandeered, and chaperones found to escort the parties hither and yon.

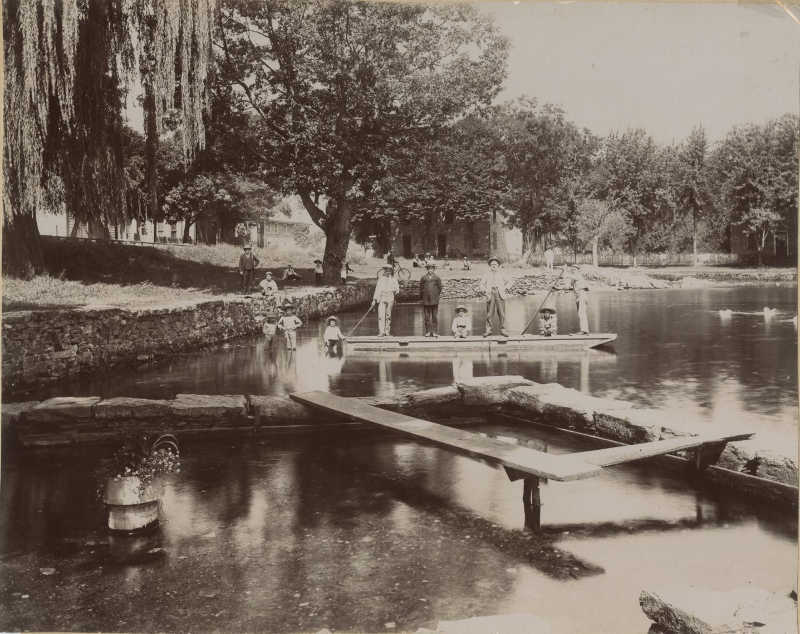

Albumen print of the lake at Boiling Springs, Pa. The background includes two homes on Front Street, the Breckbill house, and the Tavern. There is a boat on the lake and a number of men and children on the boat, in the water and on the shore (09-A-15).

Harry Strickler was in possession of a relic from the battlefield at Gettysburg. It was a six-pound bombshell charged with powder and bullets.1 It nearly cost him his life.

On Saturday morning, October 27, 1888, Harry decided to open the shell and empty its contents. He placed the shell in a wheel barrow in his machine shop and began unscrewing the cap. In the process, the shell exploded and blew the wheel barrow to bits and sent wood and shell fragments flying. Strickler was knocked down, rendered deaf from the blast, and a large piece of the shell ripped open part of his leg above the knee. The neighbors who heard the explosion found Strickler, carried him into his house and summoned the doctor who sewed up Strickler’s wound. Miraculously, Strickler did not lose consciousness nor where his hands burned.2 It was a month before Harry was seen on the streets of Boiling Springs again, and he vowed to leave old army shells alone in the future.3

Harry was a mechanic and the superintendent of the Strickler Ore Bank in South Middleton Township owned by his father Jacob. Harry never married and lived in Boiling Springs with his sister Kate. Although fourteen years older than Kate, they were inseparable.

Harry “was a great fisherman, and no sooner would he hear of a person being sick than he would catch a mess of fish and send it to them.”4 The Carlisle newspapers often reported on Strickler’s fishing exploits. “Harry Strickler, who is an expert fisherman, caught 28 fine suckers yesterday. One of them weighed 2 ¼ pounds.”5 In the spring of 1894, the newspaper reported that he caught the largest snapping turtle ever found in the Yellow Breeches Creek weighing 15 pounds 2 ounces.6

Sometimes Harry was called upon to use his fishing expertise in other ways. On Sunday, August 22, 1897, Fulmer Rife of Harrisburg lost his watch in one of the “boils” in the spring. The next morning Harry arrived on the scene with his fishing pole and made the catch. The newspaper reported that the watch was none the worse for wear after 24 hours in the “boil.”7

In March 1900, Harry caught pneumonia. He died on March 28. His obituary stated that “he was a man of the kindest disposition, ever ready to do a kindly deed, and was universally beloved. He was 63 years old.”8

Harry’s sister Kate was well educated and traveled extensively in Germany and America. In May 1886, she left on a trip to Europe with Mrs. Lewis C. Faber of Carlisle and Mrs. P. W. Morris and two of her children. Mrs. Faber was born in Bavaria, and it is undoubtedly one of the places they visited.9

Kate loved chickens, and she had the finest lot of chickens in the vicinity of Boiling Springs. With “65 peepies, 100 hens and 13 of the finest kinds of roosters…she received 15 dozen and 9 eggs in five days.”10 In 1894, she erected a hen house and went into the chicken business. With 150 laying hens, the output was large.11

Kate died on April 3, 1900. Her obituary stated that “Harry and Kate lived together and were all in all to one another. Neither married, and when it was found that Harry’s illness would terminate fatally, she too took sick with no desire whatever to get well. “She wanted,” she said, “to follow Harry.”12 Kate wrote her will three days after Harry’s death, and she died four days later. She bequeathed the large case of drawers in her room to her brother Jacob, her piano to Effie Spray and the balance of her estate to her sister Fannie Hertzler.13 Kate was 49 years old. She and her brother Harry are buried with their parents in Mt. Zion Cemetery near Churchtown, Pennsylvania.

Young people eagerly anticipated sleighing parties. Once enough snow had fallen, and a destination was established, horses and sleighs were commandeered, and chaperones found to escort the parties hither and yon.

[1] Wilkes-Barre, PA, Sunday Leader, October 28, 1888.

[2] Carlisle Weekly Herald, October 27, 1888.

[3] Sentinel, November 28, 1888.

[4] Sentinel, March 28, 1900.

[5] Carlisle Weekly Herald, March 16, 1893.

[6] Carlisle Weekly Herald, April 28, 1894.

[7] Sentinel, August 23, 1897.

[8] Sentinel, March 28, 1900.

[9] Carlisle Evening Sentinel, May 16, 1911, “25 Years Ago.”

[10] Carlisle Weekly Herald, February 16, 1893.

[11] Carlisle Weekly Herald, January 25, 1894.

[12] Sentinel, April 3, 1900.

[13] Cumberland County Register of Wills, Will Book W-183.