Born on May 9, 1801 in Carlisle, Watts was one of 12 children born to David and Juliana Miller Watts. Watts’ Cumberland County roots strech back to 1760 when his grandfather, Frederick Watts when his grandfather Frederick Watts emigrated from Wales and purchased a large tract of land on the banks of the Juniata River in present day Perry County. Watt’s father, David was a well-known lawyer in the county and a member of the first graduating class of Dickinson College in 1787.1 His mother Juliana Miller Watts was the daughter of General Henry Miller, an officer in both the American Revolution and the War of 1812.2

Watts was a member of the Dickinson Class of 1819 but was unable to graduate due to financial difficulties of the college. Instead Watts spent two years in Erie County with his uncle William Miller, a leader in agriculture, politics, and railroads.3 This period of his life is generally credited with providing Watt’s lifelong interest in the promotion of agriculture.

Upon returning to Carlisle in 1821, Watts began studying law under Andrew Carothers and was admitted to the bar in 1824. Only three years later he would argue his first case before the Pennsylvania State Supreme Court. Soon after Watts began his role as the reporter of decisions of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, a role he would keep until 1845.4 In 1849 he was appointed as a Judge of the Ninth Judicial District which covered Juniata, Perry, and Cumberland Counties. The infrastructure at the time required him to ride horseback to hear cases.5 In 1851 with the advent of judicial elections Watts was unable to hold onto his seat as a Whig in a heavily Democratic area. Watts returned to Carlisle to run a law firm with John Brown Parker, until his retirement from law in 1860.

Despite his many contributions to the legal profession in both Cumberland County and the State of Pennsylvania Watts is most known for his role as the “Father of Penn State.” Watts was a strong proponent of an education that would properly prepare farmers to fully cultivate their land as well become leaders in their community. As President of the Pennsylvania Agricultural Society he successfully petitioned the State to create the “Farmer’s High School.” The school became the Agricultural College of Pennsylvania after the passage of the Morrill Act of 1862 and eventually the Pennsylvania State University.6 The school in keeping with its founding, charged a third of the cost of other institutions setting a fee of $100 for the school year, which covered not just tuition but room and board, laundry, and books among other amenities.7

In 1871 Watts took the position of Commissioner of Agriculture in the Grant Administration. Serving until 1877, he took efforts to strengthen ties between agricultural institutions as well as expending the role of the Agricultural department.8

Locally, Watts' contributions to agriculture extended to his own farms including the property known as Creekside. The 140 acre property was bought in 1857.9 Watts built one of the largest barns in Pennsylvania and one of the first bank barns along the bank of the Condoguinet Creek. The barn was also notable for its lack of cupolas. Instead it had a number of open areas beneath the eaves to allow moist air from wet hay to escape. By displacing the air in this manner it could no longer act as a conductor during an electric storm which placed the barn at a greater risk of fire.10

Perhaps Watts’ most notable contribution to the County agricultural scene was initially dubbed by the press as “Watts’ Folly.” Watts recounted the story describing a scene of 500 to 1000 individuals.

“The wheat stood well. The team was started, the cutting was excellent; the draught was not heavy, but the general decision was that one man could not remove the wheat rapidly enough from the machine. The team could not be driven more than ten or twelve rods till it was necessary to stop and rest the raker and straighten up his sheaves. Finally a well-dressed gentleman, or ordinary side and pleasant demeanor, came up and asked whether he might be permitted to remove the wheat for a few rounds. Being answered in the affirmative, he mounted the machine, and took the raker’s stand. With perfect ease he raked off the wheat, nor did he seem to labor hard. After two or three rounds the spectators reversed their former decision and unanimously agreed that the machine was a complete success. ‘Watts’ folly’ became a favorite, and thus was introduced into the Cumberland Valley the first McCormick, the original reaping machine of the United States. The well-dressed gentleman who did the raking was Cyrus H. McCormick, the inventor of the American reaper.”11

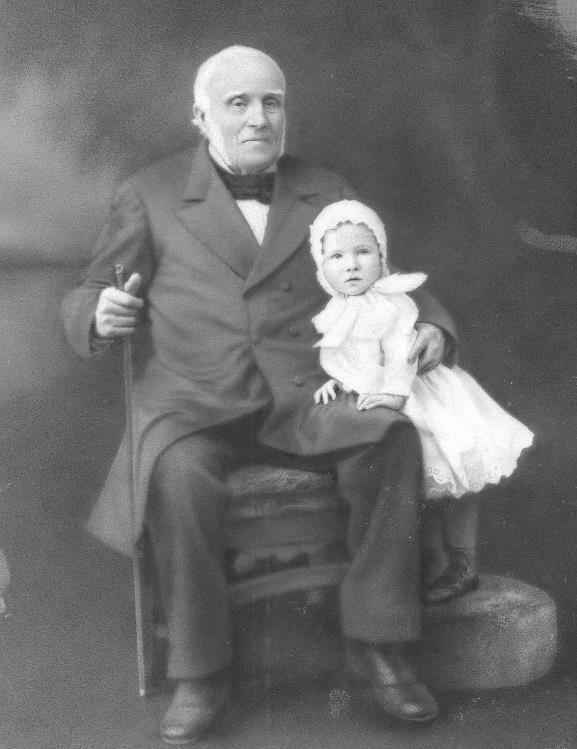

Watts lived at Creekside during the summer before wintering at 20 E. High Street in Carlisle. In addition to his many other accomplishments Watts served as the President of the Cumberland Valley Railroad, as the President of the Carlisle Gas and Water Works, and was a member of the Dickinson College Board of Trustees. The father of 14 children, he was married to Eliza Gold Cranston in 1827 and to Henrietta Ege following Cranston’s death in 1832.12 Frederick Watts died on August 17, 1889 and is buried in Carlisle’s Old Graveyard.13