The Civil War Letters of James and Ann Colwell

When the Civil War erupted in 1861, James Colwell and his wife Ann were living in Carlisle, Pa.

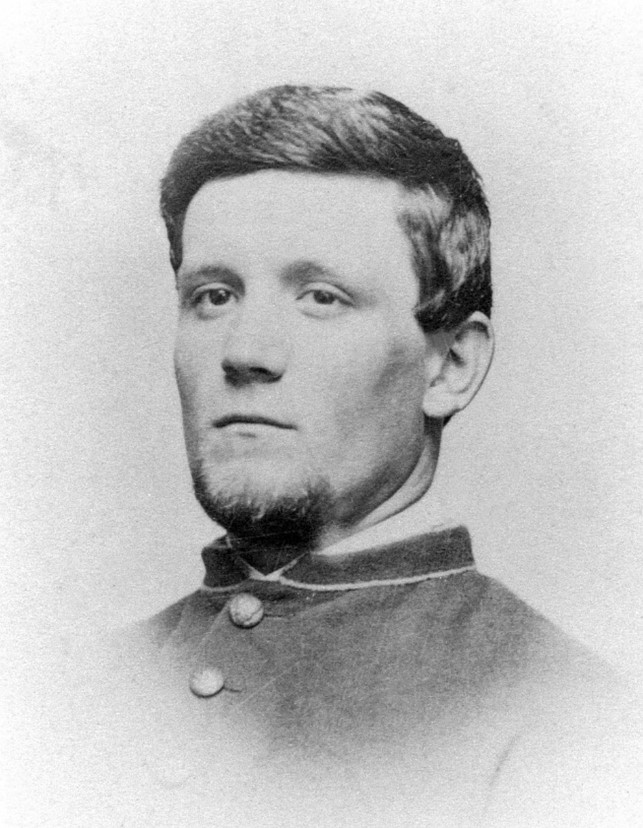

Top: John Faller

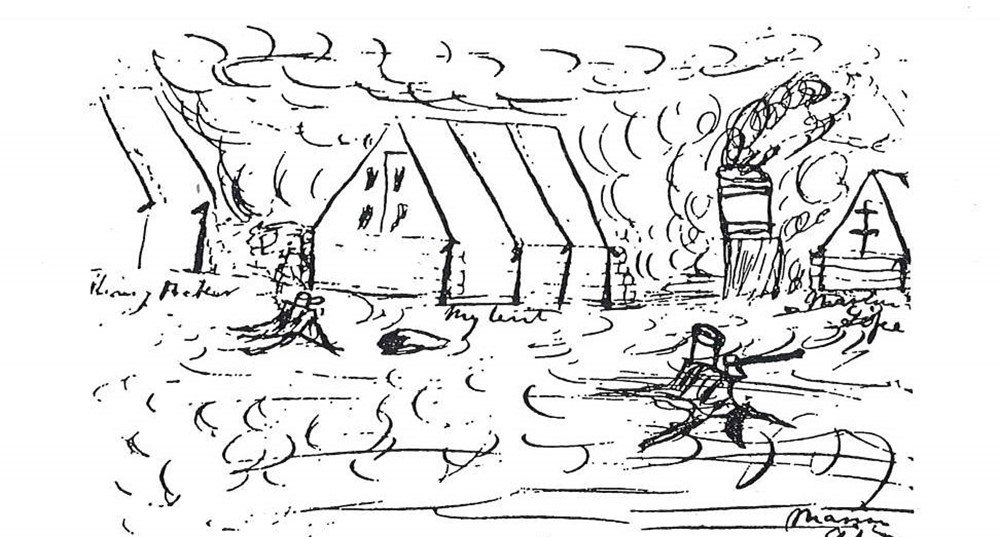

Top Middle: Leo Faller’s Sketch of Camp, Dec. 1861

Bottom Middle: The Cornfield, Antietam National Battlefield

Bottom: Providential Spring, Andersonville

John and Leo Faller were brothers from Carlisle Pa. who served in the same unit during the war. Their letters to family members provide excellent insight into the thoughts of a typical soldier. They describe their war experiences and personal observations of prominent people of the time such as President Lincoln and Gen. McClellan. As the war progressed, the tone of the letters became more serious. Tragically, one brother did not return home.

John was 20 years old when the war began, had moved from Carlisle and was working as a machinist near Philadelphia. Leo was an enthusiastic 18-year-old still living with the family in Carlisle. On April 21, 1861, Leo enlisted as a private in the 7th Pa. Reserves, Co. A; known as the “Carlisle Fencibles”. John was still working and would enlist a few months later.1

In June 1861, Leo left Carlisle with the 7th Pa. Reserves and traveled to Washington D.C. His letters to family were upbeat and humorous, as though it was a grand adventure. Along the way he once left camp without permission to explore the local area. Leo admitted in a letter that he and friends were “going out on French tonight” (June 10, 1861), which was slang for absent without leave (AWOL). At another stop he saw an Irish officer giving a speech and was impressed. Leo noted the officer proclaimed, “With Ireland and America together we could whip all creation” (June 25, 1861).

On their way to D.C., the 7th Pa. Reserves went through Baltimore, which was known for its southern support. A few months before, Baltimore citizens attacked a Massachusetts regiment when it passed through the city. As the Pa. Reserves approached Baltimore, orders were issued that if attacked in the streets they should return fire and “if attacked from the houses they were instructed to set fire to the buildings”. 2 Leo described the tense experience, “It would not have been good for the Baltimoreans if they molested us for every man had his musket loaded…” (July 26, 1861). He noted that the residents “kept mighty quiet” and they passed through without incident.

After the 7th Pa. Reserves arrived in Washington they participated in several reviews for President Lincoln and Gen. McClellan, commander of the army. At a review, Leo overheard McClellan ask the President if “he would ride along the regiments.” Lincoln replied, “Certainly, I will treat them all alike” (Aug 23, 1861). Leo described the loud cheering for Lincoln and McClellan during the review, “The President seemed to enjoy the scene very well. He stood up in the carriage all the time and laughed and talked to the men as he rode along.” Leo then joked that McClellan praised the 7th Pa “because he saw me in it.” He continued, “Gen. McClellan and the President wanted me to come and take tea with them but I told them I had some business to attend to.”

At another review, Leo critiqued the riding styles of Lincoln and McClellan in a letter to his sister. He concluded that Lincoln was “not a good horseman. He had to hold the bridle with both hands and stick his feet in the horse’s sides to keep from falling off. Gen. McClellan is a splendid rider. He dashed along and sits his horse as if he was a part of him” (undated letter).

Meanwhile, John Faller had become dissatisfied with his job and enlisted as a private on August 21, 1861. He traveled to Washington to join his brother in the 7th Pa. Reserves. He was disappointed with the look of Washington and wrote that the Carlisle courthouse “looks nicer than the Capitol itself” (Aug 25, 1861). The brothers were on picket duty near the Potomac River when they came under fire for the first time. Leo wrote home that he picked up a piece of cannon shell “as a memento of my first fight” (Sept 3, 1861).

The first battle the brothers witnessed was the small battle of Dranesville in northern Va. on December 20, 1861. Their unit did not participate but they observed another Pa. unit known as the “Bucktails”. The battle scenes appeared to shock the brothers as John described in a letter, “Some of the dead had their heads blown off and some had their legs and arms shot off. One of the bucktail boys went up to a rebel and cut his chin off and a wounded rebel was asking for a drink of water and a bucktail run up and killed him. That was brutish” (Dec. 23, 1861).

The 7th Pa Reserves went into winter quarters near Fairfax, Va and the brothers seemed to enjoy military camp life. They were eating well and had a fireplace in their tent. John wrote, “We are living high now. We draw fresh beef every other day” (Feb 6, 1862). He even noted that they ended a nice meal “with a bottle of wine”. The brothers described a tranquil camp scene where soldiers were “playing the banjo and singing Negro melodies while the rain is beating on the canvas roofs of our houses…” (Feb 19, 1862). Leo included a sketch of their camp in a letter home.

John was promoted to corporal in March 1862. Initially, the captain could not decide which brother to promote and wanted the brothers to decide. John wrote home that “Leo was perfectly willing to let me have it” (March 6, 1862). Later that month Leo saw an accident involving Gen. McClellan. The General was riding on a pier when a plank broke, and his horse fell. Leo noted, “When the General got up he said to the soldiers around him, ‘boys, your general came very near getting hurt’, jumped on his horse and rode off with only a slight scratch above the eye” (Mar 31, 1862).

The 7th Pa Reserves moved to Falmouth Va. in April to support Gen. McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign against Richmond. The regiment was part of Gen. McDowell’s Corps and Lincoln arrived to review the troops. In a letter home Leo seemed to make a fairly accurate assessment, “I think the President came here to hurry McDowell up. That is my opinion” (May 24, 1862).

In June, the 7th Pa Reserves reinforced Gen. McClellan near Richmond. Leo wrote an innocent observation which proved to be very perceptive, “The Rebels must be reinforcing their position in front of our Division as we could see a great many regiments coming up…” (June 19, 1862). Less than a week later the Confederates launched a major offensive, known as the Seven Days Battles, against the Pa Reserves’ position.

Leo described his battle experiences in a letter on July 12, 1862, after the fighting had ended. At the Battle of Mechanicsville, June 24, Leo noted that the Rebels charged three times “and each time they were driven back with great slaughter.” The next day at the Battle of Gaines Mill Leo stated, “We fired volley after volley into them…until we had the ravines piled full of dead rebels.” Eventually, the Union army was forced to retreat.

The next battle at Glendale, June 30, the Pa Reserves again took the brunt of the Confederate attacks. The battle was described as hand-to-hand fighting that “continued with a desperation and recklessness rarely paralleled in warfare…”. 3 In the confusion, Leo lost sight of John and joined another regiment in a counterattack. He received a minor ankle wound and had his bayonet “broke in two by grapeshot.” Leo eventually rejoined his unit, and the army continued its retreat. When the fighting ended, Leo summed up the Seven Days Battles in his letter, “If anyone tells you the rebels will not fight just tell them to come down to this neck of country and try them on” (July 12, 1862).

The Union army was then recalled to northern Va. and the brothers participated in the Battle of 2nd Bull Run. Leo suffered another wound when, “… a minnie ball passed through my hat and scraped my head pretty hard…” (Aug 31, 1862). John also received a slight wound on the hip. John must have impressed his superiors because he was promoted to sergeant on Sept. 1, 1862.

The Confederate army then invaded Maryland and the armies clashed at the bloody battle of Antietam on Sept. 17, 1862. The 7th Pa Reserves fought through the famous Cornfield on the north end of the battlefield. The unit was positioned at a fence near the cornfield when it received orders to withdraw. As the regiment fell back, Gen. Sumner rode up and ordered it forward stating, “I want you to again advance to the fence in your front, on the rising ground in front of the enemy”.4 The order was obeyed at a fearful cost. During the advance, a single cannon shell exploded in their midst and five members of Company A were killed or mortally wounded.

The blast killed Capt. Colwell, leading the advance, and Leo Faller was mortally wounded. Leo was struck in the thigh, groin, and below the knee. When Leo fell, he called out to his brother and John helped him to a hospital where it was determined the wound was fatal. John wrote an emotional letter home describing Leo’s last moments, “He appeared to be in great pain and every now and then he would say ‘Lord have mercy on us’” (Sept 18, 1862). John asked Leo if there was anything he would like to tell their parents and Leo said, “Tell them I done my duty.” Leo died later that day and John buried him on the battlefield. Leo was 19 years old. His body was brought home in November and buried at St. Patrick’s Cemetery in Carlisle on Nov. 30, 1862. 5

After Antietam, Gen. McClellan was replaced by Gen. Burnside. Gen. McClellan was extremely popular with the soldiers and John was discouraged by the change. When Gen. McClellan reviewed the troops for the last time John wrote, “I could have cried when he passed us. But now he is gone and Gen Burnside is our commander. The boys don’t like him so well…” (undated letter).

At the battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862, the 7th Pa Reserves briefly broke through the Confederate lines and captured over 100 prisoners. John’s excitement is evident as he described it in a letter, “Oh you should have seen us making them burn. I believe I killed several of them. The poor fellows wanted to surrender and they would run toward us with their arms raised crying, ‘for God’s sake don’t shoot us, we will give up’” (undated letter). During the breakthrough, the 19th Georgia’s flag was captured by Jacob Cart, a member of John’s company. Jacob Cart received the medal of honor for his action, and he is honored on a monument at the square in Carlisle, Pa.

The 7th Pa Reserves spent most of 1863 near Alexandria Va. and did not participate in the Gettysburg campaign. John was upset that more Pennsylvanians did not enlist to defend the State. He voiced his frustration in a letter to his sister, “Such men are not fit to be called Americans” (June 25, 1863). He also witnessed an incident at a church service in Alexandria, “The preacher prayed for the success of the Southern Confederacy and a captain with a squad of men went in and took him out before the whole congregation and sent him away” (Nov 8, 1863).

In Spring 1864, the 7th Pa Reserves marched south to be part of Gen. Grant’s campaign to Richmond. At the Battle of the Wilderness on May 5, John’s unit was surrounded by the enemy and most of the regiment surrendered. In one of his last letters home, John notified his parents that he was a prisoner of war but was doing fine. In fact, he included a surprising statement, “We have been treated first rate since our capture” (May 6, 1864). John’s attitude changed dramatically as he traveled to the infamous Andersonville prison camp.

John’s letters home stopped during his imprisonment, but his Andersonville experiences are known from a manuscript he wrote after the war, noted in the Sections below. Even though it recounts the horrors of the camp, he admitted “no one can describe the terrible sufferings that were inflicted on our men” (Sec II). Andersonville was notorious for overcrowding, starvation and disease. During its operation, about 45,000 prisoners were held and 13,000 died.6

John was sent to the prison on crowded trains that he described as, “packed like sardines in a box with the little feet of the fellow next to you lying gently on your face” (Sec II). John arrived at Andersonville on May 22, 1864 and he never forgot his first impression, “the general appearance of the place is wild and desolate” (Sec III). Men were “walking about starving to death, some without clothing…” (Sec IV). A small swampy stream ran through the camp and was used as the water supply. John described the swampy area as “one animated mass of maggots, from one to two feet deep, the whole swamp moving and rolling like waves of the sea” (Sec III). Twenty feet from the inside of the stockade was the “dead line”. Anyone who crossed it would be instantly shot.

Prisoners had to provide their own shelter and John was fortunate to bring his blanket from the Wilderness. He shared it with another prisoner to escape the sweltering sun and frequent rainstorms. John indicated he often went to the stream in the morning to get a drink, and “stepped over the bodies of a dozen men lying dead in the path” (Sec IV).

The dead were taken to the “dead house”, located outside the stockade, to prepare for burial. John described a humorous incident where a prisoner “played” dead, was taken to the dead house, and escaped. The prison commander Capt. Wirz, a Swiss immigrant, placed a guard on the dead house and remarked, “The ‘tam Yankees will run away after they are dead” (Sec IV).

By this time, the prisoner exchange system had ceased, which eliminated any hope of parole and further demoralized the prisoners. John mentions several times that the prisoners felt abandoned by their government. He noted that some men “became so despondent that they soon became insane” (Sec IV). To escape their misery some deliberately stepped across the dead line. John noticed that “men lost all feeling of humanity toward each other”. He recalled a personal incident with a fellow prisoner who he described as “the worst looking creature I ever saw. He was almost naked and covered with large sores, the maggots crawling all over his body.” The man begged for some food, but John turned him away “without any assistance or help” (Sec VI).

In addition to the abysmal conditions, prisoners were also violently harassed by fellow prisoners. A prison gang robbed and murdered sick and helpless prisoners. John provided a fascinating account of the capture and punishment of the gang members. He claimed that Capt. Wirz ordered the prisoners to break up the gang or food rations would be withheld. The prisoners created their own police force and captured about 100 gang members, including Collins, their leader. Capt. Wirz allowed the prisoners to try the gang members. The trial ended with Collins and five others sentenced to death. The rest were acquitted for lack of evidence and returned to prison. John admitted that his fellow prisoners had not forgotten the gang’s brutality. Many of the acquitted “were set upon by the prisoners as they entered and beaten almost to death” (Sec V).

The execution occurred on July 11, 1864. Each prisoner was “offered an opportunity to make statements, but all refused.” During the hanging, Collins’ rope broke, and he fell to the ground. The executioner led Collins back up the scaffold, repaired the rope, and “without further ceremony, kicked Collins off the scaffold and completed the hanging” (Sec V).

During the intense heat of August, when the prisoners were suffering from lack of water, John witnessed a miraculous event. A spring of cold, clear water suddenly appeared within the stockade “which was regarded by all as a miracle.” Thousands of prisoners gathered around it daily and it was called Providential Spring. John noted that after the war “the colored people now in that locality regard it with great reverence and have built a wall around it” (Sec VI).

In September 1864, John and most of the prisoners were transferred to a prison at Florence, S.C. John claimed that the treatment at the new camp was just as bad as Andersonville. His health had deteriorated, and all the prisoners were suffering from scurvy. John indicated “Our teeth became loose and, in many cases, would drop out” (Sec X).

Prisoner exchanges officially resumed in January 18657 and John was released on March 5, 1865. He was sent to Annapolis, MD and wrote home that he arrived there “in pretty hard condition” (March 14, 1865). John was discharged on April 3, 1865.8

John Faller returned to Carlisle and worked at the Carlisle Deposit Bank. He lectured on his Andersonville experiences and his manuscript is an important surviving record of life at the prison camp. He married and had two children that survived to adulthood: a daughter and son. John named his son Leo after his brother. John became commander of the local veteran’s organization: Capt. Colwell Post, G.A.R. The Post was named for James Colwell, another Carlisle resident killed at Antietam by the same cannon shell that killed Leo Faller. The townspeople greatly respected John and gave him the honorary title of “Captain”, as he was known in the community. John Faller died July 9, 1914, at age 72. He is buried at Saint Patrick’s Cemetery, Carlisle, PA.

When the Civil War erupted in 1861, James Colwell and his wife Ann were living in Carlisle, Pa.

Dear Folks at Home, The Civil War Letters of Leo W. and John I. Faller, Cumberland County Historical Society, 21 North Pitt Street, Carlisle, PA, 2011.

1 Bates, Samuel, History of the Pennsylvania Volunteers 1861 – 1865, Vol I, pgs. 734-735, 1869.

2 Sypher, Josiah, History of the Pennsylvania Reserves: A Complete Record of the Organization, pg. 96, 1865.

3 Bates, Samuel, History of the Pennsylvania Volunteers 1861 – 1865, Vol I, pg. 725, 1869.

4 Ibid, pg. 727.

5 Carlisle American, Vol. VIII, No. 40, pg 3, Dec. 3, 1862.

6National Park Service, Andersonville National Historical Site.

7 Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, Series II, Vol 8, pg. 65, 1899.

8 Bates, Samuel, History of the Pennsylvania Volunteers 1861 – 1865, Vol I, pg. 734, 1869.