World War II had an enormous impact on the citizens of the United States. The country was struggling for its very existence. All sections of the country felt the impact including the borough schools of Mechanicsburg.

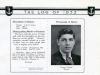

The first mention of the impact of the war on the schools came in the December 23, 1941 edition of the Mechanicsburg High School newspaper, The Torch. Stationed at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii on December 7, 1941, the day that the Japanese bombed the military base, was 1938 Mechanicsburg graduate, A. Charles Faust. The school paper reported on the incident and the fact that Faust’s parents received a telegram telling them “Everything is O. K.” Faust had survived the attack on Pearl Harbor, but war had started for the United States and students, former students and staff of Mechanicsburg schools became involved. The same issue of the school newspaper contained a picture of Faust and eight other Mechanicsburg graduates serving in an active war zone.1

The Class of 1942 was the first group of MHS current students impacted by the events of Pearl Harbor as this turn of events happened during their senior year. Interviewed at a class reunion in 2012, they could not remember how many students from the class went off to war but they were sure that all of them returned alive.2 That would not be the case with other Mechanicsburg classes.

The school administrators and teachers immediately became involved. The first way that the schools dealt with information about the conflict was by holding student assemblies. Many of the weekly assemblies of the period had a military theme. Recently returning from a campaign in Africa, Mechanicsburg native Brigadier General Ent spoke to the students on September 21, 1943 about the importance of the African campaign and the need for an allied victory. Despite the urgency, he carried a larger message to the boys in the class, “to continue with their high school studies.” 3

Periodically, alumni serving in the military would return to their alma mater to explain what life was like for a person in the military. The speaker at a 1944 weekly assembly at Mechanicsburg High was James Stoner, who joined the Navy the previous March and spoke about his experiences on active duty in the Atlantic theater.4

The following month, the weekly assembly opened with the students singing America and hearing a report of the War Bond drive that was underway at the school. The highlight of the assembly was hearing about the exploits of “Buzzy” Gehr, an aerial gunner in the U.S. Navy. Gehr explained the dangers of serving in the Navy, specifically the “narrow escapes that face the servicemen in the battles of the South Pacific.” 5

When soldiers returned on leave to Mechanicsburg, they were able to gather at the local U. S. O. hall located downtown. The facility was open to war production workers and members of their families as well as to men and women in uniform. While not a formal school activity, a number of female students served as hosts and a number of teachers served as volunteers. Superintendent of Schools Dr. Edwin B. Long was the chairperson of the U. S. O. of Mechanicsburg.6

One of the major roles of the home front during World War II was the raising of money to support the troops. The Community Chest, which existed prior to the war to support the community at large, began to raise money for the war effort. The citizens of Mechanicsburg actively supported the organization. They donated large sums of money as well as supplied a large number of volunteers. The 1944 effort saw the support of over 100 volunteers who raised money for local and national causes including the bulk of the proceeds ($8,511) for the National War Fund that directly supported the armed services. The director of the community chest that year was Superintendent Dr. Edwin B. Long. Also serving on the central committee were teachers Ernestine Hasskarl and Irva Zimmerman.7 Dr. Long was also in charge of registration for the War Ration Book distribution held at Mechanicsburg High School.8 Dr. Long was very involved on the home front and served as an inspiration to his staff.

School students participated in a number of money raising activities. As the local newspaper reported in 1941, the students of Mechanicsburg raised over $10,000 in the “Buy a Jeep” campaign. The Student Council Victory Committee under the direction of Principal James G. Haggerty administered the overall program with students participating in the drive by buying War Bonds and War Stamps. According to the article, the children of Mechanicsburg invested enough in the war effort to purchase nine jeeps, three more than the original goal of six. Samuel M. Goodyear, Cumberland County War Savings Committee Chair, recognized students of the Mechanicsburg schools for “turning in the finest record of any community in the county.” The Daily Local News also stated, “As a reward for their efforts, the students will be honored with a celebration on Friday at Memorial Park.”9 A later article explained that the celebration consisted of a parade, speeches, and music in honor of the students. Eventually the total raised was $19,391.95 or enough to purchase eighteen jeeps.10

The trend continued with the fourth War Loan Campaign which “went zooming over the top” according to an article in The Daily Local News. The children of the local public schools purchased $7,400 in War Bonds or enough to fund two Fairchild “Cornell” training planes. “Mechanicsburg High School” was inscribed on the planes.11 A one-day War Bond and War Stamp Drive held on Pearl Harbor Day 1943 resulted in the schoolchildren selling $3,832.70 worth of bonds and stamps. The funds raised were donated to the local American Legion Auxiliary to aid in their drive to purchase ambulance planes.12 According to the school newspaper, this was an improvement over the 1942 drive in which MHS pupils purchased only $1,070.70 worth of bonds and stamps.13

The campaign of 1944, the fourth time the school participated in the drive, was a huge success with the students purchasing $45,000 worth of war bonds or stamps. One way that they reached the goal that year was the sponsorship of a basketball game with the Naval Supply Depot team. In order to gain admittance to the game, students needed to purchase a war bond or stamps. Many did.14

The Community Chest and War Fund drive continued into 1945 raising $242.54. The faculty advisor, Elizabeth Orris, announced that the faculty also contributed $413 to the effort. Even though the war was over in August 1945, the money “would be used to aid hunger, cold and nakedness” left by the war’s destruction.15

Not every donation was money to purchase bonds and stamps. Also prominent in the period were salvage campaigns. A total of 26,195 cans were collected from September to December 1943. During the 1942 -1943 school year, the MHS scrap drive established a state record for the number of cans collected.16 The Daily Local News explained that the “students of Mechanicsburg were recognized by the State Salvage Committee for their participation in the three-week scrap metal and rubber drive, collecting 75 tons of material or almost four times the goal of 20 tons.” As the local newspaper also reported, “the scrap, currently piled in the rear of the high school, would be sold to a local salvage yard and the proceeds donated to the war effort.”17

The schools did more for the war effort than just raise money. The Community Physical Fitness Council held its first meeting during April 1942 with plans to set up a community recreation program. John Frederick, MHS physical education instructor and athletic coach, organized the meeting with the assistance of fellow physical education instructor, Miss Kathryn Williams. The goal of the program was to “build up the youth of the community physically.”18

Community Victory Gardens were as popular in Mechanicsburg as they were in the rest of the country. The community garden was located at the Hasskarl plot located at 16 East Marble Street. Ernestine Hasskarl, a history teacher at the Mechanicsburg Junior High School, was the daughter of the property owner. The victory garden chair for the borough was Albert Mowery, the vocational agricultural instructor at Mechanicsburg High.19 It was not enough to grow the food, it also needed to be prepared and preserved, and the schools were involved in all steps of this educational activity. During May 1943, more than 50 women gathered in the home economics suite of the high school to witness a public canning demonstration as a feature of the local victory garden program.20 The local Red Cross sponsored a twenty-hour long nutrition class for members of the community. High school home economics teachers Miss Erma Nissley and Mrs. I. Eugenia Spangler were the instructors.21

Because so many men went to the military there was a shortage of workers on the local farms. If not harvested, the crops would rot in the fields and the season would be lost. James Haggerty, then the Senior High Dean of Students, recruited boys and girls over the age of ten to volunteer their services at the local farms and spend the day picking berries and beans.22

The Cumberland County American Legion Essay Contest always had a patriotic theme. The theme of the 1943 contest, “For This We Fight,” left no doubt how the sponsors felt. Mechanicsburg student Betsy Heagy won the contest that year.23 Even the debate team got involved with the war effort. “Resolved, that as permanent policy every able bodied male citizen in the United States should be given one year of full time military training before the present draft age” was the national debate topic for the 1941 – 1942 academic year.24

The school practiced civil defense drills during the period. During an aid raid, students living in Mechanicsburg returned to their homes while rural students went to the homes of friends. In case of an unexpected air raid, students were to stay in the school. Certain windows of the high school had hardware cloth screens installed to prevent glass falling into the hallways during an air attack. As the school paper reported “To date, the students had practiced one drill and were expecting to practice more.” The paper reported that during the initial drill, the school emptied of all students within five minutes and the streets were clear within ten minutes.25

The high school curriculum was altered to meet the needs of the war effort. There was a change in the type of physical education coursework at the high school with a greater emphasis on calisthenics, broad-jumping, rope climbing, marching, and running. The pre-industrial shop class was re-designed to teach boys the fundamentals of shop tools and machines and “enable them to obtain better positions in the armed forces.” Two girls enrolled with 47 boys in the machines class, the purpose of which was to teach the laws of machines and motion.26

In order to free more men for active military duty, one idea considered at the Pennsylvania State Education Department was the elimination of summer breaks allowing the move from a three-year to a two-year course of study for high schools. Mechanicsburg Superintendent E. B. Long did not support this move and the state did not adopt the change.27

The United States Defense Department in conjunction with the Department of Vocational Education in Harrisburg offered training courses for boys from 3:30 to 11:30 pm five days a week. Courses included auto mechanics, pattern making, radio servicing, aviation sheet metal, oxyacetylene welding, and electric welding - all skills needed to fight the war. Trainees successfully completing the courses were able to obtain civil service certificates. The federal government paid the entire bill so there was no charge for registration, tuition, or supplies.28

On November 9, 1943, high schools across the country, including Mechanicsburg, offered tests for civilians interested in Army and Navy specialized training programs. The program was offered to civilians between the ages of 17 and 22 that were “either a high school graduate or would be a graduate by March 1, 1944.”29

During the war years the high school library contained a section devoted to War Information that would be useful to students who were planning to enter the military after graduation.30 During 1942 the United States government required the registration of all males between forty-five and sixty-five years of age. In Mechanicsburg this occurred on April 25, 1942 in the library on the second floor of the high school building on Simpson Street. Schools closed that day and registration occurred between the hours of 7 AM and 9 PM. Forty-five members of the faculty helped with registration.31

The military draft was part of life at Mechanicsburg. According to an article in the school newspaper, the high school cooperated with the Selected Service program by having the Guidance Department complete and submit the initial paperwork for students that were entering the armed forces. The same edition of the newspaper pictured eleven male students who were in the Army and Navy Enlisted Reserves.32

Like most communities during the era, Mechanicsburg schools sent their boys and girls to fight in the Allied Forces campaign. The December 23, 1943 edition of The Torch was dedicated to “Our Fighting Boys and Girls.” The issue listed the Mechanicsburg graduates who were men and women in the Armed Forces. Over 500 names were listed from the classes of 1916 to 1948 including 54 from the Class of 1942.33

Each month the school newspaper published a column listing stories regarding MHS men and women, including members of the faculty. Listed in the paper were military addresses of service men and women from Mechanicsburg High. The paper also printed letters sent to the school from men and women in the military.

The members of the high school Journalism class sent letters to teachers who were on leave while in the service. One member of the staff that replied was a history teacher, Lt. Reida Longanecker. She wrote, “If anyone joined the Army to get away from school and education they certainly joined the wrong organization. The Army is one continuous learning process.” The same issue of the newspaper listed the names and military addresses of the eight faculty members that were serving in the Army and the Navy.34

One way that the students at home helped in the war effort was to send copies of the school newspaper to Mechanicsburg service members.35 In addition, students would send MHS service men cards for special occasions such as Valentine’s Day.36 During the winter of 1943, the school cooperated with the Mechanicsburg Chamber of Commerce to address letters to service men and inserted the letters inside Christmas packages mailed to “boys in the field.”37 Dick Stephens, from the Class of 1942, wrote back stating how happy he was to receive his school newspaper “because it takes me back home for a few minutes.” He also stated that he was pleased that the folks back home still think of him.38

The school kept track of high military honors received by former students and published the accolades in the school paper. The Torch reported in November 1943 that former student Lt. William Hendrian was the first MHS alumnus to receive the Oak Leaf Cluster. He was a fighter pilot with the Army Eighth Command and he received the Army Air Medal for combat duty “somewhere in England.”39 The Torch reported that Jim Stone received a presidential citation for his work on the U. S. S. Card, an escort aircraft carrier that was part of a team that had been “sinking more submarines than any other combined in Naval History.”40 On February 10, 1944, The Distinguished Flying Cross was awarded to Mechanicsburg’s William McLaren who served as a gunner on 25 combat missions over enemy territory.41 Eleven days later, the same newspaper reported that McLaren was missing in action over occupied France.42

While many left school for the military, there was an influx of new students resulting from new families moving to the area who were working on construction of the Naval Base on the north end of town. Many of these students lived in Hampden Township and attended elementary school in the Hampden Township School District but attended high school in Mechanicsburg as tuition paying students.43

To fill the teaching ranks for teachers who entered the military, the district needed to hire substitutes. One such substitute teacher was science instructor Albert Brechbill, who taught the previous eight years at Messiah Bible College in Grantham.44 Brechbill taught at Mechanicsburg Senior High during the war and returned to Messiah in 1946.45 Two other instructors left for different reasons. Mrs. Rheva Poindexter taught commercial subjects at the high school until August 1945 when she announced her resignation so she could travel south to “join her husband who returned to the country from overseas service in the European Theater of Operation.”46 Mrs. Sivick was hired to teach in the commercial department at the start of the war.47 She remained on staff until her resignation in December 1947 because “her husband, Dr. Edward Sivick, was returning to the area after being stationed in Japan.”48

Teachers serving in the military came from both the classroom and the coaching ranks. Football coaches John Fredericks and Carl Hamsher were on military duty during the war as was head baseball coach, Boyd Fortney.49

A large number of students dropped out of high school to enter the military. Some soldiers thought about returning for their diplomas after the war. One soldier did more than think about high school while in the military. Pvt. David Franklin Messinger, who would have been in the class of 1944 but left during his junior year to join the military, earned enough credits while in the Army to receive his high school diploma. Messinger graduated from Mechanicsburg High School in absentia with the class of 1945.50 Five members of the Class of 1948 completed their G. E. D.s and received diplomas on graduation night of that year. Listed in the newspaper were Leslie I. Anderson, Charles A. Myers, George Z. Hamilton, Robert Dale, and William Himes.51 Some waited a bit longer to receive their diplomas. On June 3, 2002 five individuals, Donald Beistline, Elmer Brice, James Neff, Harry Yohn, and Richard Merris, were recognized by the school board and administration as Mechanicsburg High School graduates. According to then Principal Richard Bollinger, “these individuals cut short their high school career to join the armed forces after Pearl Harbor and were part of the force that stemmed the tide of Japanese and German aggression in the world.”52

The war ended in 1945 with the German surrender in May 1945 and the formal surrender of Japan in September of the same year but Mechanicsburg High School continued to report about the men and women who fought in the war. An article in the March 27,1945 edition of The Torch listed sixteen former students of Mechanicsburg High that were killed in action as well as four that were prisoners of war and one listed as missing in action. Later confirmed among the soldiers killed in action was MIA soldier, Thorley Hollinger.53 A May 1945 supplement to the Mechanicsburg High School newspaper, The Torch pictured eighteen “sons of MHS who paid the supreme sacrifice.” The supplement included a military biography of each service member.54

On November 14, 1947, the renovated Mechanicsburg High School football field was officially renamed “Soldier and Sailors Memorial Park” prior to the varsity game with Chambersburg “in honor of all World War II Veterans.” As the program for the evening stated, “We especially dedicate these improvements to the memory of our brave sons who unselfishly gave their lives to preserve our free institutions and make possible the building of a better America.” The coach for the game was John H. Frederick, who had returned to the Mechanicsburg sidelines after serving in the United States Navy during the 1942 and 1943 football seasons.55

During 1948, the Superintendent of Schools, Dr. E. B. Long, appealed to the citizens of Mechanicsburg to forward to him the names of any Mechanicsburg service man who paid the supreme sacrifice in World War II. The plaque containing the names of the service men was placed at the entrance to Mechanicsburg Athletic Field at Memorial Park.56

By the end of the war, the list grew to include the 22 named below57:

IN MEMORIAM

Samuel C. Anglin, Jr.

Ernest Martin

William A. Beck

Robert Martin

F. Lester Derrick

Joseph Myers

Miles F. Goodman

Paul Myers

Robert M. Gribble

Harold Peterman

William Guyer

Paul Runk

Thorley Hollinger

Donald Rutherford

David Lee Kistler

John Westfall

David C. Kurtz

Paul Westhafer

Paul R. Lowery

Joseph Whitman

William McLaren

Edgar Wickard

In 2004, John W. Ent, Lieutenant Colonel in the United States Army Reserve (retired) published Heroes Among Us. In this self-published work, Ent recounted the military achievements of World War II veterans who attended Ent’s alma mater, Mechanicsburg High School. Working with the Mechanicsburg High School Alumni Association and reviewing the newspapers and yearbooks of the period, Ent compiled a list of those who served in the military during World War II and contacted as many as possible. The book serves as a testimony to those from Mechanicsburg who served during the war.58

Recently, a group from the Mechanicsburg Middle School recognized the service of men and women who participated in the war by sponsoring the Central Pennsylvania Honor Bus, operating from 2008 to 2015. The veterans of World War II and the Korean Conflict had breakfast at the Mechanicsburg Middle School followed by a bus ride to Washington DC to visit memorials honoring their commitment to the wars. The trip included a stop in Arlington Cemetery to view the Changing of the Guard at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. On the way home, the group stopped for a final dinner at the Dillsburg American Legion. The idea for the Honor Bus came from middle school students and their advisor, Mrs. Rebecca Lacey.59

Often, high school annuals of the 1940s dedicated an edition to a person or a school related activity. The 1944 Mechanicsburg High School yearbook, the Artisan, stated, “To those in our class who have forsaken the halls of MHS to follow the road to victory, we humbly dedicate this book.”60 The students and staff of Mechanicsburg can be very proud of the efforts and sacrifices they made to support the war effort.