Few things have stood out as more quintessential of an American small town than its barbershop, and fictional representations of those towns, whether Mayberry or Mitford, have been sure to portray the local barber, an affable and steadfast character.1 For generations of loyal customers, a barber named Harold Stone seemed to be a permanent institution in a small town that The Wall Street Journal had once called “the middle of nowhere.”2

Roy Harold Stone, universally known as Harold, often as Stoney, was a barber in Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania.3 There he worked from the late 1920s into the early 2000s, that is, from his days as an apprentice at the age of fourteen until his retirement at the age of ninety-two. Thus for nearly eighty years he was a fixture in that small town, and part of the word of mouth advertising for his barbering business came through the frequently overlapping circles in which he moved, circles that included his religious, military, political and social affiliations.

Stone was born in Hagerstown, Maryland, on 22 June 1914, to Roy B. and Mamie A. Stone, but he grew up in Mechanicsburg. According to the 1920 Census, the Stones rented a place in the borough’s first ward, a two-story frame house at 19 West Keller Street, and by then the family included three other children, two girls and another boy. Mr. Stone worked as a house carpenter, and by 1930 he had bought a two-story frame house at 203 West Maplewood Avenue, just off South High Street, near the cemetery. Since 1920 two more boys had been born to the Stones. The Census of 1930 was the first to inquire about ownership of radios, and so it duly recorded that the family owned a radio.4 A radio would feature throughout Harold’s working life.

In Mechanicsburg, young Stone attended public school, and in 1933 he graduated from Mechanicsburg High School. In those days the borough’s high school was at the corner of West Simpson and South High Streets, a large, square structure built in 1892 made of brick and granite and slate in the Romanesque Revival style, a building of massive arches and lofty turrets. Adjacent to it was an additional building, brand new in Stone’s day; begun in 1926 and completed in 1929, the new building was in a Gothic Revival style, yellow brick with brownstone trim. It had an auditorium, and it was there that high school graduation exercises took place.

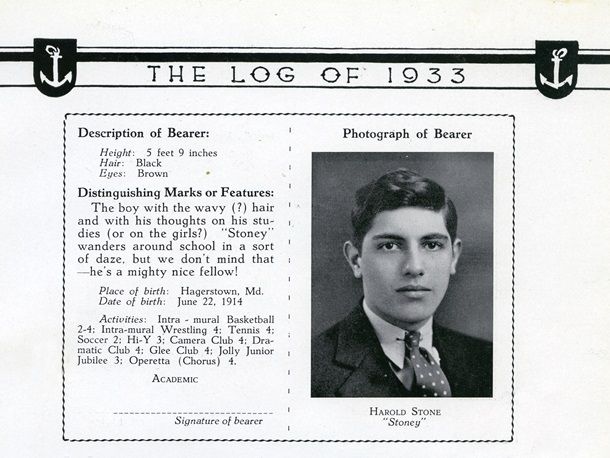

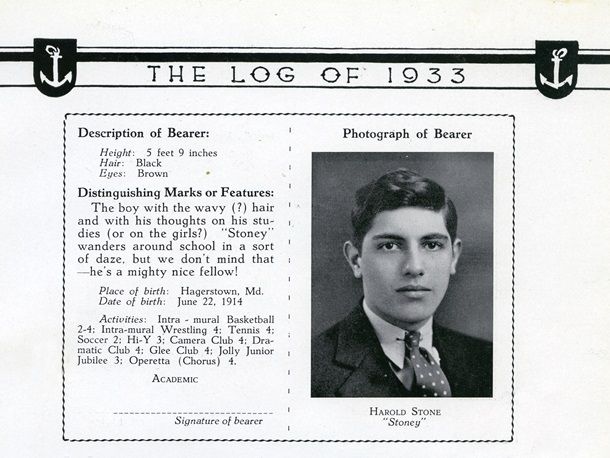

Mechanicsburg High School yearbook. CCHS yearbook Collection.

Mechanicsburg High School yearbook. CCHS yearbook Collection.

According to Stone’s senior year high school yearbook, he had been active in school, participating in wrestling and tennis, the camera club and the glee club.5 His black and white photograph in the yearbook shows a pleasant-looking young man with dark eyes and dark wavy hair parted on the left. In later years he was active in the school’s alumni association and attended class reunions, and in the 1960s he and his wife supported the school’s wrestling team.

Stone was also an active member of trinity Evangelical Lutheran Church on East Main Street in Mechanicsburg. A brick and brownstone structure on the south side of the second block from the town square; it is symmetrical in its proportions and had in Stone’s boyhood recently received extensive repairs and renovation. Among other alterations, its soaring steeple had been replaced with a domed cupola in 1908.6 In a later renovation, a steeple was place back on the tower. The shape of Stone’s growing up years was thus described by landmarks only a few blocks apart.

In the summer of 1928 Stone was hired as an apprentice by William C. “Bill” Harrold, a native of Dauphin County who had become a barber in Mechanicsburg.7 His obituary in The Evening Sentinel noted that in addition to barbering for fifty years, he was a Freemason and taught in the Presbyterian Sunday School. According to the 1920 Census, Harrold, age 54, was the son of German immigrants. He had been barbering for some forty years. In 1880, that year’s Census recorded that he was nineteen and living with Conrad Kaffensberger and his wife, Anna. Conrad Kaffensberger was a barber from Germany. These two Census records place his birth as either 1866 or 1861; Harrold served as Kaffensberger’s apprentice. Thus, by 1928, Stone, as Harrold’s apprentice, was part of a traditional way of learning a craft, although unlike Harrold in his apprentice days, Stone lived at home with his parents. In his turn, over the years Stone also had apprentices. These men then went on to receive their barber licenses and opened their own barbershops.

Trinity Evangelical Lutheran Church. CCHS yearbook Collection.

Being a barber was a relatively clean, safe, indoor occupation, and a trade men would always need. As an apprentice, Stone worked seventy to eighty hours a week and was initially paid two cents an hour. Male vanity being what it was and is, some customers objected to an apprentice practicing on them. Others, however, were less worried about their appearances and recognized that the boy had to learn his job somehow. Stone would recall Harrold’s strict and taciturn style, one example of which was a simple downward wave of his right hand to signal to Stone to lower the blinds against the afternoon sun. If Stone were busy sweeping the floor or doing some other chore and missed seeing that signal, Harrold would become impatient and scold the boy for his inattentiveness.

Naturally frugal, Stone saved his money, and when Bill Harrold died of cancer, Stone was able to take over the business. So it was that in late 1933 Stone opened the barbershop, opposite the Station Master’s House on Strawberry Alley, as his own. In the spring of 1941 he moved nearby, around the corner to 7 Railroad Avenue, where his illuminated red, white, and blue barber pole turned for the next sixty-six years.

From 1943 to 1945 Stone served in the United States Navy. He had been drafted8 and sent to the naval base in San Diego, California. Although he had resolved that once in uniform he would not be a barber, as soon as word got around that he was a professional barber, both there on base and then on board ship in the Pacific he was in demand to cut men’s hair. years later he recounted to a customer that one day while still on base he was summoned to appear before his commanding officer. As Stone stood before him, that officer observed that Stone had been cutting the men’s hair. “I thought I was going to be reprimanded,” Stone recalled. Instead, the commanding officer asked Stone whether he would cut his hair as well.

In September, 1945, near Okinawa, Japan, while on board the U. S. S. Repose, a hospital ship, Stone feared for his life during a typhoon with waves of 75 feet and winds up to 145 miles an hour.9 Stone’s war years were his longest absence from Mechanicsburg, but that time away proved to be a formative one. He was a charter member of the Mechanicsburg chapter of the Veterans of Foreign Wars, and he also belonged to the American Legion.

For the rest of his life, Stone, a reticent and disciplined man, maintained a military crew cut and the pencil mustache fashionable in the 1940s and 1950s. With the exception of an annual vacation, first taken in 1972, he worked Monday through Friday, as well as Saturday morning. For decades, his shop held the aromatic tobacco smoke of his plain black billiard pipe.

Beginning in April, 1952, Stone belonged to Eureka Lodge 302, of the Freemasons in Mechanicsburg.10 As a Mason, he was eligible for and long enjoyed membership in the Zembo Shrine, an imposing Arabesque edifice near Italian Lake in Harrisburg. Because of these memberships, he also belonged to the Cumberland County Shrine Club. He wore a Masonic ring, and he and his wife attended various dinners and conventions hosted by the Shriners.

Although a registered Democrat, Stone claimed to have voted for the rival political party ever since what he regarded as a big mistake, voting in 1936 for Franklin Delano Roosevelt. From that time onwards he was a reliable supporter of Republican candidates, and hourly news from a radio always playing in the shop could prompt from Stone laconic but unambiguous commentary.

The 1960s radical changes in American social trends tended to leave Stone ill at ease. Let one anecdote suffice. Like most anecdotes it may have developed in the retelling, but it conveys historical fact and much truth about the man and his character. Word spread rapidly amongst Stone’s clientele when in the late 1980s a teenager came into the shop and requested a Mohawk, a style then somewhat in vogue. Stone knew the young man’s parents and immediately telephoned them to ask whether it was all right. Accounts vary about whether he ended up giving the boy the haircut.

By their nature, fads come and go, however much they may fail to charm a barber who saw and looked askance at shaggy or spiky styles brought about by the likes of the Beatles and punk rockers. Other changes came with less obvious reaction. For example, from time to time the potted plants in the shop were probably pruned or replaced. More noticeable, by the 1990s the shop had become smoke-free, and, more ominous, in the wake of concerns about hepatitis and AIDS, there appeared in the shop a handmade sign saying simply, “No Shaves.”

Barbers have long had a reputation for garrulity, and Plutarch recorded in Book VI of his Moralia that as far back as the fifth century B. C., when a barber asked King Archelaus of Macedon how he would like his hair cut, the king replied, “In silence.” Still, Stone was not of that type. With the murmur of the radio blurring into the background, it was possible to receive a haircut from Stone with little or no attempt at conversation or even monologue, such as fills a short story by Ring Lardner, “Haircut.” on one occasion, Stone’s sustained silence allowed a customer to drift far away into thoughts about one thing and another. The haircut done and the customer’s hand reaching for the door of the shop, there came a voice up to that point never heard, such was its sharp note of authority: “Hey! you forgot to pay me!”

Stone's Barber Shop at 7 Railroad St. CCHS yearbook Collection.

Stone’s barbershop occupied much of the ground floor of a white, three-story house on the west side of Railroad Avenue.11 up two sets of two curved concrete steps one approached two wooden doors painted red. Between the doors was a window. The door on the left opened on to a hallway that led to the upper floors and Stone’s residence. The door on the right took one into the barbershop.

His shop was decorated in the Art Deco style, and three red and black barber chairs stood opposite three large mirrors. The metal National Cash Register was from the 1930s, the Coca-Cola machine from 1950. Under the window beside the front door was always a box of toys to entertain small children. Children and adults enjoyed watching the tropical fish swimming about in two fish tanks set at right angles in a back corner of the shop. Farther back in the shop, in a small waiting room, there was a wooden table with some Masonic and hunting magazines, and on a metal stand in the back corner there was a small black and white television.

Stone married on 8 June 1935, the former Jean Cranford (1915-2008) of Camp Hill, and they remained together until his death.12 They had a daughter, Rickie Jean. Stone’s wife, one of the first women in Pennsylvania to receive a barber license, assisted him in the shop. For the most part, she prepared customers for their haircuts, attaching towels and aprons to the customers and shaving their necks. She also took her turn sweeping hair from the floor and doing the shop’s laundry. Customers were sometimes treated to the banter of this long-married couple. Much of a barber’s life is spent in public, and these conversations about shopping or dinner or the grandchildren gave patrons of the shop a sense of being part of an extended family.

Stone traveled widely with his wife. In addition to having a weekend getaway cabin in Perry County, each year the Stones took vacations either across the country or around the world. Their first vacation was when they were in their late fifties. One day Stone surprised his wife with tickets for a Caribbean cruise, a surprise leaving her in a flood of tears: she could not understand why he was sending her away on her own, the thought that he would close up the shop and go with her never occurring to her.

From that time until their eighties the Stones were intrepid travelers. A large map of the world hung on the wall of the shop opposite the mirrors and near the cash register. Some fifty red push pins marked places visited by the Stones, from Bermuda to Australia, Russia to Egypt. Near the map were displayed color snapshots of the couple in front of the Taj Mahal and other sights.

The longevity of barbers gets the attention of journalists.13 Stone was no exception, and in his eighties, Stone became the subject of features in the local newspapers. His wife also appeared in those articles, and the Stones shared with reporters some of the stories they had often told to their customers. In August of 2006 he was the subject of a poem on the back cover of DreamSeeker Magazine.14 The poem reflected Stone’s declining years and his wife’s awareness that even though he was slowing down, he still needed something to do. For these writers and others as well, Stone came to represent a link with the past, a living reminder of an America popularly associated with the paintings of Norman Rockwell, a world and a way of life that appeared to be fading away.15

As with any long-running business, customers could become complacent and assume that Stone’s barbershop would always be there. Nevertheless, at the end of December, 2006, Stone did the unthinkable and retired. One Sunday almost a year later, on 18 November 2007, he died at home, and, as he had requested, there was a Masonic funeral at Myers Funeral Home in Mechanicsburg. Instead of flowers, contributions were to go either to his Church or to his high school’s alumni association. The following year, after his wife died, his ashes and hers were scattered on the grounds of their cabin.

Mechanicsburg High School yearbook. CCHS yearbook Collection.

Mechanicsburg High School yearbook. CCHS yearbook Collection.