Surrounded by the perfectly-aligned, white marble sentinel headstones of almost one-quarter million American war veterans, explorers, historical figures, and national leaders, Chief Warrant Officer Eugene Robert Orth's mortal remains rest in Section 35, Grave 3523 of the Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington, Virginia, encircled by the graves of an Army Master Sergeant from North Carolina and a Private First Class from Virginia, a Coast Guard Captain from Massachusetts and a Navy Lieutenant Commander from Pennsylvania. Shaded by an evergreen and two cherry trees, the gravesite lies about two hundred yards south of the Tomb of the Unknowns in gently sloping terrain. On 14 April 1966, a partly cloudy day in the nation's capital with a temperature in the low 50s, and just over one year after his U.S. Navy retirement, " ... Orth .. . of Mechanicsburg, P[ennsylvani]a, formerly of Bellows Falls, [Vermont] died ... at the Walter Reed Hospital in Washington, D. C. " Attending physician Army Dr. Gerald Smith listed the cause of death as "cancer of the lung, congestion, heart failure, [and] peneumonitis radiation type." While tourists braved the cool spring weather to gaze at the delicate pink and white blossoms on the over 3,000 Japanese-donated, mostly Yoshino cherry trees surrounding the District of Columbia's Tidal Basin in West Potomac Park, businessmen considered a proposal to broadcast television signals into homes via a satellite system, politicians read that the president of Iraq had been killed in an airplane crash in his country's city of Basra, and travelers noted that Pan American World Airways placed the airline industry's first order for twenty-five of the new Boeing 747 jumbo jetliners, Eugene Orth's family grieved. Four days later, they interred the former sailor in Arlington for his eternal rest. His wife, two children, three sisters, and his mother survived him.

Only one decade after leaving active duty, Orth's life had ended at fifty-one years, statistically about twenty years premature for a mid-twentieth-century American man. His life's story was one common to Great Depression-era young men in the United States - no opportunity for a post-secondary trade school or college education, greatly limited prospect for work, responsibility for a financially struggling family, and close, firm family ties. His success in life had come through military service.

His enlistment had provided Orth with opportunities that Navy recruiters had touted. His military career had been one of excitement, education, travel, advancement, and adventure. Unfortunately, in early 1942 during the beginnings of America's participation in the Second World War, it had also included deadly nighttime combat action aboard a doomed cruiser against superior Japanese forces in the Java Sea concluding with his capture and imprisonment as a prisoner of war (POW). To say that his almost thirteen hundred days as a POW in various Japanese internment camps in Java suffering tropical disease, surviving on inadequate rations, and performing grueling coolie labor shortened his life would be accurate.

* * *

The ten-thousand-ton heavy cruiser USS Houston (CA-30) lies on her starboard side one-hundred-thirty-odd feet under the surface of the Java Sea, her bow heading roughly east. Shell holes perforate the ship's steel superstructure in several areas, particularly the bridge and port aircraft hangar bay. Eight-inch gun Turrets Two and Three are ripped loose from the warship and lay nearby amidst various pieces of debris. Four Japanese Type 93 "Long Lance" torpedoes exploded below the great ship's waterline, holing her hull in three places on the starboard side and one on the port. The 600-foot vessel, once capable of a speed of over thirty knots, defiantly flew the Stars and Stripes as she sank, her beautiful clipper bow piercing the sea bottom during the early morning hours of 1 March 1942, the eighty-fourth day of America's forty-six month participation in the Second World War. Nicknamed by her sailors "The Galloping Ghost of the Java Coast" because of previous Japanese claims to have sunk her, Houston took with her to the depths of the Java Sea two-thirds of her crew, a total of 721 officers and men, including Capt. Albert Harold Rooks, her commanding officer of six months, who posthumously received the Medal of Honor. The Japanese later captured 366 Houston sailors and Marines from the oil-slicked sea and on various beaches on the northwest Javanese coast. They sent the majority of these prisoners of war to Burma to serve as slave labor in building the Burma-Thailand Railway, appropriately named the Death Railway, and a bridge on the Khwae Noi (or River Kwai), which was made famous in a 1957 David Lean film that won seven Academy Awards. The Japanese scattered the rest to ten different prison camps in Japan, Thailand, Java, Malaya, and the Philippines. Although seventy-six Houston survivors, slightly over 20 percent, died in captivity building the railroad, 290 others, including Pharmacist's Mate Second Class (PhM2/c) Eugene Robert Orth, survived an ordeal of filth, depravation, disease, and brutal treatment during three and one-half years in Japanese prisoner of war camps throughout Asia. These men of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet's flagship were among the first Americans to be taken prisoner by the Japanese in the Second World War.

The interwar-Navy was a small, professional, volunteer fighting force composed of officers and men of considerable experience and training. Officers were generally Naval Academy graduates, some chief petty officers had tours of a dozen years on the same ship, and enlisted men were likewise well seasoned. No new enlisted men were aboard Houston in the 1930s for two reasons; because of the Great Depression, volunteers were more abundant than the minimal available slots necessary to fully man the peacetime fleets, and conscription would not be enacted until 1940 in preparation for the Second World War. Pharmacist’s Mate Second Class Orth was a veteran of almost six years’ service when he joined the Manila-based Asiatic Fleet aboard Houston one year before the Second World War began for America.

The U.S. Asiatic Fleet had been created in the 1850s to protect American interests in the Orient, primarily in Manchu China. In the early twentieth century, U.S. Navy Asiatic Fleet Yangtze River patrol boats were frequently called upon to protect and evacuate American businessmen and missionaries and to escort U.S. merchant ships sailing the river. The mission of the Shanghai-built river gunboat USS Panay (PR-5) was engraved on a bronze plaque in her wardroom: “For the protection of American life and property in the Yangtze River Valley and its tributaries, and the furtherance of American good will in China.” While Houston and other capital ships of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet made port visits to show American power, Panay and her eleven sisters plied 1,300 miles up the coffee-colored Yangtze implementing it. As the century progressed, Japan’s shadow spread more and more over China.

On a manufactured incident orchestrated by her army’s officers, Japan invaded and conquered Manchuria in 1931, renaming the puppet state, Manchuko. In August 1937, continuing their violence in China, Japanese forces attacked Shanghai, and by the end of the decade, Japan had subjugated much of China. Western nations opposed Japanese aggression but took little action. Tensions between the U.S. and Japan reached a summit on 12 December 1937, almost four years to the day before the Pearl Harbor attack, when Japanese military airplanes bombed and sank Panay and three Standard Oil river tankers she was escorting on the Yangtze River, steering the two countries toward collision.

Two U.S. sailors were killed and seventy-four other military and civilian personnel wounded in the attack. Among the wounded were the gunboat’s captain, Lt. Cdr. James J. Hughes, and Far Z. Wong of Hankow, who had enlisted in the U.S. Navy as a Chinese citizen and would win the Purple Heart for wounds received on Panay. Subsequently a shipmate of Eugene Orth onboard Houston, Wong would later be declared missing in action with her loss.< Panay, her topside painted with two large American flags and a large, holiday-sized national ensign flying on her stern, had been sent to the Chinese capital of Nanking to aid Americans fleeing from the invading Japanese. This loss of an American warship to the Japanese no doubt caused naval officers to dust off plans for war with Japan.

In the two decades before the beginning of the Second World War, the U.S. developed a naval strategy for a Pacific war with Japan designated the ORANGE Plan, which provided for the Navy’s Pacific and Atlantic Fleets to rendezvous with its Asiatic Fleet in Manila in “a trans-Pacific projection of American power.” Upper echelons of the government and leadership of the armed forces agreed upon the necessity of the plan, but not upon funding its support. Congress believed that the nation’s military existed only for defense of the homeland and cut naval forces to half of what the admirals wanted. From the Navy’s viewpoint, “supporting elements . . . had always been woefully inadequate.” The ORANGE Plan called for the Asiatic Fleet to check the Japanese aggression in Asia and to strategically retreat, grudgingly trading space for time until reinforcement arrived from the Pacific Fleet putting to sea from Hawaii and the Atlantic Fleet sailing through the Panama Canal; on 7 December 1941, however, a new reality set in.

Without benefit of reinforcement from either the Atlantic or Pacific Fleets and the Pacific war clearly of secondary importance behind the European theatre, the Asiatic Fleet tried to inflict maximum damage on the enemy while husbanding its scarce assets and retreating toward the Malay Barrier (now Indonesia). With the nearest American naval base 5,000 miles away in Hawaii and the powerful Japanese fleet sailing in between from island bases granted them after the First World War, the Asiatic Fleet could expect neither reinforcement nor resupply.

The Japanese, who “had expected heavy air, submarine, and surface opposition” in the Philippines found none, invaded the nation, pounded the U.S. Army forces, destroyed the U.S. Army Air Corps units, and forced the American Navy to withdraw from Manila and disperse south. Nippon cornered American and Philippine ground forces on Corregidor Island in the entrance to Manila Bay and on the Bataan Peninsula west of the Philippine capital and north of Corregidor. After Maj. Gen. Douglas McArthur, Commander of the U.S. Army Forces – Far East, and his staff left Corregidor for Australia, vowing to return to defeat the Japanese, thousands of Americans and Pilipinos fought and died or surrendered to become prisoners of war. On 26 December 1941, Adm. Thomas C. Hart, Commander of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet, moved his headquarters out of Manila, taking with him all of the fighting ships that could possibly be used to defend the Malay Barrier and to slow the Japanese Navy’s progress toward Australia. The Americans joined the British, Dutch, and Australians in the multi-national ABDA force, “the war’s first integrated Allied supreme command,” which lasted six weeks. The strategic withdrawal south became a rout, and within three months’ time in late 1941 - early 1942, the U.S. Asiatic Fleet passed virtually unnoticed into history as young courageous, professional sailors and Marines fought desperate battles against superior numbers of well-trained and well-equipped Japanese sailors of the Nihon Kaigun. Among these Americans was Eugene Orth, a twenty-seven year old sailor who had been in the Orient since 1939.

Born on 5 January 1915 in Rhinelander, Wisconsin to Silas and Ednah Thomas Orth, baby-of-the-family Eugene Robert Orth joined three older sisters, Margaret (Peg), Theodora (Ted), and Francis. Silas moved his family from Illinois to Wisconsin to Bellows Falls, Vermont, a small town on the state’s southeastern border on the Connecticut River halfway between Rutland and Manchester, New Hampshire. Whether his moving the family was for better income, more security, wanderlust, or some other reason is not known. In Bellows Falls one evening, in Hollywood melodrama-style, Silas Orth went out for a package of cigarettes and never returned home, abandoning his wife and children and leaving his young son the figurative man of the family. In 1928 when Orth was thirteen, his estranged father died, leaving the young man nicknamed Gene, Pee Wee, or Buster the literal man of the family.

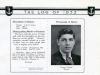

Orth enrolled in Bellows Falls High School’s Class of 1933. A popular and active student, his 1933 school yearbook noted him as the “Best Dressed Boy” in his Senior Class, Vice President of his Freshman and Senior Classes, a member of the All-State orchestra for three consecutive years, and a letter-winning varsity football player in 1931. “Gene always has the appearance of stepping out of a band box,” the yearbook remarked and then asked rhetorically, “What is your secret of making all the girls gaze upon you so wistfully, Gene?” “He was the best looking boy in his high school class,” remembered Ellen Mary Griffin, a fellow student and two years Orth’s senior at Bellows Falls High School. The yearbook also recorded his ambition to be a registered pharmacist.

On 15 June 1933, Orth graduated high school, and he began working at Shaw’s Drug Store in town. After eighteen months at Shaw’s, he applied for enlistment in the U.S. Navy. With a single, working mother and three sisters at home, he would have no opportunity to attend college in order to pursue his dream of becoming a pharmacist. Naval service would provide a way to obtain skills and experience for future civilian pharmacy employment and a means to secure an income for his mother and sisters.

When Orth considered his future in 1933, one-quarter of Americans who wanted to work could not find a job. The Great Depression was at its worst point. When Orth applied to enlist in the Navy, the service could afford to be selective about recruits because the number of applicants far exceeded the number of available openings to the extent that only one in eighteen applicants was accepted. Prewar Navy enlisted men were long-term personnel who found the security of service life preferable to an uncertain future in civilian employment. Because it was costly for the Navy to transfer personnel, the service reduced transfers to a minimum. Some chief petty officers were known to have been assigned to the same ship for a dozen years, and during the depression reenlistment rates among enlisted men soared to about 90 percent. These high reenlistment rates and the stable size of the inter-war Navy meant fewer positions available for new recruits; consequently, few and only the best men were taken into the service.

On 26 December 1934 Orth, who was one of only two successful Navy enlistees from Vermont that year, received orders from the U.S. Navy Recruiting Sub-Station, Rutland, Vermont directing him to undergo a final physical examination two weeks later in Springfield, Massachusetts. The author of the letter, Recruiting Sub-Station Officer-in-Charge Chief Water Tender William Carroll, ordered him to limit his personal effects and further advised, “If there is [sic] any cavities in your teeth have [them] filled before reporting to this station.” Orth passed the Navy’s physical, and on 8 January 1935, three days after his twentieth birthday, he transferred for training to the U.S. Naval Training Station, Naval Operating Base, Norfolk, Virginia and began a twenty-year active duty military career. Naval Training Station Commanding Officer Capt. B. C. Allen, USN, wrote Orth’s mother stating that he was “glad to inform” her that her son “has reported on this station and is undergoing training and instruction in the duties of the Naval Service.” The command assigned Orth to Platoon No. 1 for training.

After graduating Basic Training and qualifying as an Apprentice Seaman, Orth trained as a Hospital Apprentice at the Hospital Corps School, Portsmouth, Virginia, graduating on 23 August 1935 with a 94.66 percent final average. He was subsequently ordered to the U.S. Naval Hospital at Newport, Rhode Island. This posting probably pleased him because it was close to home and allowed him to visit family and friends in Vermont, notably young Ellen Griffin, whom he knew and dated in high school. She remembered him with Easter and Christmas cards, and they addressed each other familiarly as “Pee Wee” and “Griff.” They enjoyed dates on the town; in a note to Orth, Ellen wrote, “How well we celebrate.”

Orth served a total of four, likely pleasant years at Newport, which would end with an overseas tour far from family, friends, and sweetheart. On 7 January 1939, after four years on active duty in the Navy, he extended his active duty for four more years and was promoted to Pharmacist’s Mate Third Class. In May, just over two years since the sinking of Panay on the Yangtze, the Navy transferred Orth to the Philippine Islands, and he boarded USS Henderson in Norfolk, Virginia bound for San Diego “and all points west of there.” The voyage to the American west coast would take a month during which time Henderson would visit Guantanamo Bay, Cuba and Cristobal, Canal Zone; pass through the Panama Canal to Balboa on its Pacific end; and stop at San Diego, San Pedro, Mare Island Navy Yard, and San Francisco, California. After leaving San Francisco for the Philippines on 29 May and making a port call at Pearl Harbor in early June, Henderson passed the 180th Meridian at north latitude 20° 56’ 00” at 10:52 P.M., Sunday, 11 June 1939, at which time Orth “was duly inducted into the Silent Mysteries of the Far East” and, along with the other “pollywogs” on board, was appropriately initiated into the “Imperial Domain of the Golden Dragon” by the ship’s “shellbacks.”

After his arrival in the Philippines in mid-June 1939, Orth reported for duty at the U.S. Naval Hospital at Canaçao, his first duty assignment in the Far East. While Philippine-based sailors considered the cheap prices, rousing adventure, and exotic life in Asia “good duty,” Orth’s letters do not indicate that he was thrilled about a tour in the Orient or that he found it a shopper’s paradise. In fact, in a letter written shortly after his arrival, he penned, “as far as I am concerned I’m ready to go back [to the United States]. That of course is only my first impression of the Philippines and it may change with time but I’m not sure. . . . It’s hotter than the hinges of hell here.” With the humidity level as high as the temperature, Orth and his shipmates were required to “keep an electric light bulb burning in our lockers all of the time to keep our clothes from moulding [sic]. You can judge from that just how damp it gets.” He wrote his sister Ted about his initial impression of the work life at the Canaçao Naval Hospital, “Speaking of conserving energy – the motto out here is no strain-no pain. Nobody does much apparently and likewise nobody seems to care.”

Beginning in December 1940, one year before Pearl Harbor, he transferred aboard USS Houston, which the month before had arrived from Honolulu and become Admiral Hart’s flagship. The almost twenty-six year-old sailor was a veteran of six years’ naval service when he climbed the gangplank to report to the Medical Department of the Asiatic Fleet’s flagship. In early 1941, after having been assigned to the “H” (for hospital) Division aboard Houston, he advised his mother in a letter written in port at Manila that he doubted that “we [will] get to China this spring so you all may be disappointed at not getting any souvenirs from there. . . . I doubt if you will get anything from here either. I haven’t seen anything as yet worth spending ten cents on except State-side made products.”

Ever the dutiful son, family matters concerned him, particularly his mother’s welfare and happiness. Orth wrote his sister Ted, “I’ll write [sister] Peg after I get thru here & give her the dope [Navy slang for “information”] too. . . . I never got a chance to send mother anything for Easter. I feel really ashamed of myself -- so how’s to get her something -- better late than never.” He had taken out an allotment from his Navy pay to support his mother, and, in a letter to Ted, asked her and his other two sisters not to “spend any of your husbands’ hard earned dough to support mother” because he had “increased [his] allotment specifically for her use.”

Letters from home were precious to Orth as they were to all servicemen away from home. Regular mail took five weeks to travel from the Philippines to Vermont, with postage for a first class letter at three cents and for a postcard, one penny. While airmail service was quicker, it was considerably more expensive; postage for an airmail letter from the Orient cost seventy cents.

After the U.S. entered the war, the sailors’ mail was subject to U.S. Naval Censors. To speed the mail by reducing the censors’ workload in the post-Pearl Harbor days, the Navy provided sailors and Marines with penny postcards preprinted with impersonal information that they could use to get unclassified messages home. The instructions for the message side of the card read, “NOTHING is to be written on this side except to fill in the data specified. Sentences not required should be crossed out. IF ANYTHING ELSE IS ADDED THE POSTCARD WILL BE DESTROYED [capitals appear in the original].” Sentences that a writer could select for inclusion or deletion included:

Orth sent home some of these preprinted postcards from early December 1941 through February 1942 when Houston sailed from Manila into harm’s way and mail could neither be sent nor received by her crew until she made a scheduled port call. Letters sent to him from Vermont in early December 1941 were marked “RETURN TO SENDER” by the post office. Houston’s mail never again caught up with her.

Houston entered the Second World War escorting U.S. Navy fleet units out of the Philippines enroute to Darwin, Australia as the fighting withdrawal of U.S. Naval forces commenced. In early February, with her crew disgusted with escort duty and desiring a fight, she rendezvoused east of Java with three light cruisers and seven destroyers to seek out and annihilate Japanese ships in the Flores Sea. Without protective air cover, this attacking force was itself hit by Japanese airplanes, which specifically targeted Houston, the largest ship in the force. During the battle, a five hundred pound bomb struck just forward of and disabled her after eight-inch turret and killed nearly four dozen sailors.

On 28 February 1942, Houston, along with the Australian cruiser Perth and Dutch destroyer Evertsen, lay in port at Batavia, Netherlands East Indies. The Battle of the Java Sea, the first surface engagement between the Allies and the Imperial Japanese Navy, had ended the previous day. With their loss of one heavy cruiser, two light cruisers, and five destroyers, Allied surface forces were virtually eliminated as a threat to Japan and presaged the fall of the entire Malay Barrier to Nippon. Admiral Hart ordered all fleet vessels, except for its submarines, out of waters north of Java, abandoning the area to the Japanese.

Because no major dockyard repair facility was available, Houston’s badly damaged after eight-inch turret remained out of commission and the forward mounts were nearly out of ammunition. Men loaded and hand-carried on bed sheets 260-pound eight-inch projectiles and bags of gunpowder from the after magazine to the forward magazines and handling rooms serving Turrets One and Two. Not only did the recent action seriously deplete Houston’s magazines, it also significantly shortened the tubes’ 300-salvo life and dangerously degraded their accuracy. Turret One had loosed 261 salvos since its installation, 97 alone during the afternoon of the Java Sea engagement. Turret Two had fired 264 salvos total, 100 that same afternoon.

The repeated outgoing concussions and incoming explosions took their toll. The once-elegant flag cabin where Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt had stayed during his “four cruises totaling 25,445 miles aboard Houston” “was a shambles, wrecked by repeated concussions, so that even the soundproofing was torn from the bulkheads.” The concussions had also torn loose the sailors’ personal items that had not been securely fastened down, including uniforms, pictures, radios, lockers, drawers, and mirrors. The bridge windows were blown out, fire hoses were full of shrapnel holes, and the ship was taking on water due to near misses that had loosened her hull plating. Despite the serious damage, Captain Rooks reported that -- “Houston was ready, willing, and able to fight.”<

Having been informed by Dutch intelligence officers that there were no Imperial Japanese Navy forces along their route and leaving an uninformed-on-the-plan Evertsen behind, Houston and Perth sortied at 7:30 P.M. and made for the Sunda Strait (the location of the massive, August 1883 explosion of the Krakatoa volcano) and a hoped-for successful escape into the Indian Ocean. At 11:15 P.M. under a full moon the Sunda Strait was in sight as was a force of ten Japanese destroyers led by a light cruiser. Two other Japanese heavy cruisers lurked nearby, out of sight. The battle commenced as the two Allied ships opened fire on the destroyers and light cruiser force.

Unknown to the commanding officers of Houston or Perth, these eleven observed enemy ships comprised only part of the protective force for the largest amphibious landing yet attempted by Japan. Approximately sixty transport ships screened by an additional force of an aircraft carrier, four heavy cruisers, and an unknown number of destroyers and motor torpedo boats comprised an invasion force destined for a landing in Bantam Bay, Java. The American and Australian cruisers charged the Japanese transports but were quickly mobbed by the covering force. The ensuing battle between capital ships was fierce and deadly, and the Allies were clearly outgunned.

By twenty minutes after midnight, Perth was empty of ammunition and sinking, her captain and over half of her crew going down with the ship. Houston also fired everything she had, including, at the last, phosphorous-filled illumination shells. Japanese admitted losses included three transports and a minesweeper sunk and a tanker, four destroyers, and a light cruiser damaged. Historians judge from eyewitness accounts and ships’ logs that an additional two destroyers, an aircraft transport vessel, and three motor torpedo boats were also sunk and four additional transports and a destroyer beached.

The Japanese fired eighty-seven torpedoes at the two cruisers, and an unknown number of them missed the Allied ships and struck and damaged or sank their own invasion fleet’s vessels. Out of ammunition, afire, listing to starboard severely, holed by three torpedoes on her starboard side, guns wrecked, and maneuvering severely restricted, Houston was doomed and Captain Rooks knew it. He ordered the crew to abandon ship and was then himself killed by an exploding shell. Japanese motor torpedo boats and destroyers raced in, illuminated the sinking Houston with searchlights, and raked the cruiser’s decks with gunfire. A Japanese destroyer put one last torpedo into the defenseless cruiser’s port side, and she sank at 12:45 A.M. taking two-thirds of her officers and men with her. The tragic end of a gallant ship was but a beginning of an almost unbelievable time of trial for her surviving crew.

During the clash, Pharmacist’s Mate Second Class Orth’s battle station on Houston was a compartment that was used as a triage and battle dressing station. At one point in the ship’s last battle, a Japanese shell penetrated her hull and exploded in Orth’s assigned compartment, killing twelve of the thirteen sailors inside. Orth, the sole survivor, was miraculously unscathed. When the “abandon ship” bugle call sounded, he managed to get to the main deck, jump overboard, and join hundreds of his shipmates trying to avoid the Japanese sailors’ machine-gunning Houston survivors. Cold, oil-soaked, and still dazed from the explosion in his battle station, Orth swam for six to seven hours in the currents of the Sunda Strait, which threatened to sweep him out to sea, before reaching a Javanese beach. For the 1,298 days between the sinking of Houston on 1 March 1942 and his release on 18 September 1945, Orth was a prisoner in seven different Japanese POW camps in Java, Netherlands East Indies.

While an exhausted and waterlogged Eugene Orth struggled ashore in Java only to be captured and imprisoned by the invading Japanese army, his family knew little of his fate. On 14 March 1942, two weeks after the loss of Houston, an official telegram came from Radm. Randall Jacobs, Chief of the Navy’s Bureau of Navigation informing Ednah Orth that her son was “missing following action in the performance of his duty and in the service of his country.” Rear Admiral Jacobs cautioned Mrs. Orth, “To prevent possible aid to our enemies please do not divulge the name of his ship or station.” There was no need for secrecy on the part of the family; at that same time newspapers all over the country reported Houston’s sinking. Headlines declared, “12 Allied Ships Lost; Java Battle Costly to United Nations; U.S. Cruiser Houston, Destroyer Pope, Among Victims.” Another newspaper ran a 1939 picture of Houston transiting the Panama Canal with the caption, “Flagship U.S.S. Houston—One of the American warships which went to the bottom off Java in a furious naval battle with the Japs. The Houston, battling overwhelming odds, sank with her mighty guns still barking at the enemy.” The next day, a third’s headline proclaimed, “Twelve Warships Lost by Allies in Java Sea, 5 of Them Cruisers; Japan Loses 7 Damaged or Sunk – Houston is Lost.” The disturbing news about Houston’s crew was reported erroneously, which, unknown to Ednah Orth, provided no consolation; “It appears definite . . . that the 10,000-ton heavy cruiser Houston, one of President Roosevelt’s favorite vessels for cruises, was lost with all hands.”

When Orth came ashore on the north coast of Java following his ordeal in the sea, Japanese soldiers captured him and marched him with some of his Houston shipmates for three days and two nights to a mountain location near Cheribon, a city on the Javanese north coast about 130 miles east-southeast of Batavia (now Jakarta). The captives were “forced to endure ‘bashings’ from the Japanese, who used their rifle butts to keep the men moving.” At Cheribon, Orth and twenty-nine other prisoners began their three and one-half year life of brutal treatment by living together in an eight by twelve foot hut and subsisting on coconuts given them by the Japanese. The captors gave the men fourteen coconuts every other day to be divided among the POWs, but gave them no water. Orth lost about thirty pounds of body weight during his six weeks at Cheribon.

In mid-April 1942, the Japanese trucked the entire Cheribon POW population inland to a camp (or a “native jail” as Orth later described it) in Rangkasbitung, about fifty miles southwest of Batavia. Fed a cupful of dry rice per day with little water to drink, he slept on a bunk made of boards in a nine-man cell. Orth spent only two to three weeks at this camp. It and Cheribon were but way stations to a larger, more comprehensive prison; Orth’s next prison camp was a former Dutch installation in Batavia.

Arriving in the last half of May 1942, Orth’s prison home for the next four to five months was the “Bicycle Camp,” the former home of the Dutch Tenth Battalion, a unit of bicycle soldiers of the Netherlands East Indies Army. Beside the camp’s long entrance road, POW barracks stretched over a hundred yards. Separate billeting for Dutch, Australian, British, and Americans was provided and the concrete block barracks had red tile roofs and porches. POWs subdivided the barracks into cubicles and “slept on bamboo platforms that lined either wall.” The camp had running water and sewers, relative luxuries to the five thousand POWs interned there.

Orth worked in the camp’s hospital along with the other survivors of Houston’s medical department, including its two doctors, Cdr. William A. Epstein and Lt. Clement Burroughs, and pharmacist’s mates Al Kopp, Raymond Day, Griff Douglas, and Lowell W. Swartz. There was no proper medicine or laboratory equipment and when disease came, there was no defense. Although the Bicycle Camp would offer the best prison conditions he would experience as a POW, Orth considered it the smaller Rangkasbitung prison the best camp of all those in which he was a POW. It was at the Bicycle Camp that Orth contracted jaundice and became too ill to be drafted into heavy construction work in Japan, China, or Burma.

His illness may have saved his life because all of the Houston sailors who died in captivity expired on Death Railway slave labor gangs. On 4 June 1942, the Japanese began shipping POWs from Batavia to Singapore to work on the Burma-Thailand Railway by moving 500 men there. On 1 August they relocated another 500 men to Singapore and in October 1942, the Japanese shipped over 8,200 prisoners, many of them Houston men, from Batavia to Singapore for railroad construction work.

Because he had had medical training, the Japanese sent Orth for six months to work in a “hospital” at a camp at Tandjong Priok, the seaport for Batavia. He watched his friend, Canadian Bud Everson, who had served with the British Royal Air Force, leave with a draft of over 2,000 British prisoners for Haruku Island POW camp. Two years later, only 115 men returned, Everson not among them. In about March 1943, Orth was among forty to fifty men whom the Japanese moved to Batavia and a camp called Mater Della Rosa.

Japanese captors directed that Orth and his fellow POWs set up a “hospital” for prisoners at Mater Della Rosa. The prisoners worked about four months on the facility, and when it was finished, the Japanese used it not for the POWs but for civilian women and children internees. Orth remembered that the food was better at this camp, even though the men were allowed only a few potatoes and a small amount of meat. Using the Japanese script money they occasionally earned for POW work, the prisoners managed to buy eggs at a cost of 15 to 20 cents each. It was while he was at Mater Della Rosa, one year after Houston went down, that Orth’s family discovered that he was no longer missing-in-action.

America’s first realization that Orth was alive was a short wave radio message read by an announcer at 7:15 PM, Eastern War Time on Wednesday, 24 February 1943, and broadcast over Radio Tokyo (station identifier JLG-4) on a frequency of 15.105 megacycles. The program, called the “American War Prisoners Information Hour,” opened with a rendition of “My Bonnie Lies over the Ocean” and then a Japanese announcer, in heavily accented English, read a fifteen-second message composed by the imprisoned Orth:

This message is from Orth, Eugene Orth, Orth spelled O-R-T-H, Eugene Orth, age twenty-seven; his rank, Pharmacist’s Mate Second Class of the U.S. Navy. His home address is 9 Atkinson Street, Bellows Falls, Vermont [address repeated] 9 Atkinson Street, Bellows Falls, Vermont; and this is his message. ‘Dear Mother, Best wishes to you and the kids for the holiday season. I am in good health and spirits. Hope to be home sometime next year. Love, Buster.’

Orth apparently wrote the message during the Christmas holiday season of 1942 and the Japanese broadcast it the following February. On signing off, the station once again played “My Bonnie Lies over the Ocean.”

On this program, Radio Tokyo broadcast messages from one to four American prisoners of war on multiple frequencies at the same time. The messages about Orth had slight, but important differences. Listeners heard on one frequency that he was imprisoned in Batavia, Java, that he wanted his family to send candy, bullion cubes, and shaving soap, and that he needed his mail sent through the International Red Cross in Geneva, Switzerland, details missing from other broadcasts. The nightly program, a powerful propaganda tool for the Japanese, was heard on both U.S. Government listening stations and private radio sets all over North America.

Ednah Orth also got dozens of postcards, letters, and telegrams from well-wishers who heard the broadcast and who lived all over the United States and Canada. Mail came postmarked from friends and strangers alike; people who felt it their duty to help others needed to share this joyous information with sorrowful and hopeful family members. The good news came from a Dodge automobile dealer, an Internal Revenue Service agent, a Catholic priest, a doctor, a greeting card salesman, a Navy flyer, a chiropractor, a Michigan county clerk, an Iowa mayor, and several mothers with sons in the armed forces. Some who wrote also had sons who were missing or captured and could understand the powerful effect on families that this good news had. Parents of Houston sailors wrote to inquire if Orth had been assigned to the ship. Written messages came from New York, Rhode Island, California, the District of Columbia, Connecticut, North Carolina, Illinois, Texas, Pennsylvania, Louisiana, Nevada, Colorado, New Mexico, Iowa, Massachusetts, Arizona, Maine, Michigan, New Jersey, Ohio, Utah, New Hampshire, Minnesota, and Montreal and Winnipeg, Canada. Even if it was from strangers, the contact was wonderful and left the family with a feeling of relief. Ednah Orth answered every piece of correspondence she received.

Shortly after North Americans heard the live broadcast of the message written by Orth, three phonograph disc recordings of the broadcast arrived at Ednah Orth’s Bellows Falls home. Ham radio operator R. P. Read of Hopkins, Minnesota made the first of these records from his private short wave radio set. At his own expense, Read produced and sent his records to relatives of the POWs he heard mentioned in the Radio Tokyo short wave broadcasts. The second record was made by another ham, Gordon Gurney of Los Angeles, California, on a disc donated to him by the American Safety Razor Corporation, Gem Division. This record had on one side a photographic mural of “Authentic scenes of Gem reporters making thousands of free Voice-O-Graphs throughout the nation.” While this free-to-the-recipient record was “one of Gem’s contributions to the morale of America’s armed forces and the folks back home,” it clearly produced significant advertising value for the American Safety Razor Corporation. The third record was from the War Prisoners Monitoring Station, Long Beach, California, an arm of the U.S. Government’s foreign radio monitoring network. This record was of sturdier material, appearing to be of similar quality as 1940s phonograph records, and was apparently intended for repeated playing on a phonograph. It was simply labeled, “Orth, 2-24-43.”

On 10 March 1943, two weeks after the Radio Tokyo broadcast, Rear Admiral Jacobs, now the Chief of Naval Personnel, again wrote Ednah Orth that “more than a year has elapsed since your son . . . was placed in the status of missing.” Since Public Law 490, 77th Congress, as amended, authorized the Secretary of the Navy to continue a sailor in the status of missing-in-action until an acceptable proof of death was found, Rear Admiral Jacobs informed Mrs. Orth that the Navy would continue to list her son as missing since no evidence had been received by the Navy about Orth from the International Red Cross, the official medium of information exchange. This had financial significance for Mrs. Orth whom Orth had allotted a portion of his pay as his dependant. It meant that Orth’s pay would “be credited to his account and any allotments registered in his behalf of his dependents” would continue.

Rear Admiral Jacobs wrote Mrs. Orth again on 7 June and the news was good to read. “An official cablegram from the International Red Cross has been received from Tokyo, via Geneva, stating that your son . . . is being held as a prisoner of war at a Java Prison Camp.” Two weeks later a second Radio Tokyo broadcast gave additional good news of Orth.

Dear Mother, Another short note to let you know I am still in good health. Don’t do any unnecessary worrying and take good care of yourself. I hope to be home in the near future but, until such time, will write at every available opportunity. Buster.

The Army intercepted this 30 March broadcast and on 18 June, Col. Howard F. Bresee of the Office of the Provost Marshal General wrote Ednah Orth, “The War Department is unable to verify this message and it is not to be construed as an official notification.” In bleak contrast to the positive messages clearly orchestrated by his captors, Orth struggled to survive in Java.

In the summer of 1943, the Japanese sent Orth to a camp called St. Vincentins where he was captive for almost two years. The Japanese paid POWs a “daily rate of pay [of] fifteen cents per Diem (Japanese inflation script) if a prisoner was able to work.” At one Christmas, about one thousand prisoners pooled their resources and bought a 130-pound pig from a local Javanese man. The POWs made the pig into a stew and all men got one ladle of broth and a cup of rice for Christmas dinner. When rice became scarce and the Japanese stopped its distribution to the prisoners, the POWs made flour from coconut shells and baked dark, heavy, greasy bread. The Japanese weighed each man monthly, and if a prisoner looked too healthy, the captors cut his rations.

Japanese treatment for infractions involving food was severe, often fatal for the POWs. Attempts to buy or barter for food with the natives without captor permission was treated harshly. Orth remembered one particularly cruel and brutal Japanese sergeant nicknamed “Bamboo Marai” who was a guard at St. Vincentins. When Marai discovered that a POW had stolen a piece of fish, the guard chopped off the prisoner’s head with a samurai sword.

Orth received two packages while at St. Vincentins, one from his sister Peg Butler and one from the Red Cross. Shown his sister’s package’s contents, he had to write an acceptable “thank you” note before he could receive the package. The Japanese rejected his first note as too short. His second attempt was accepted and eventually received by his sister.

In 1943 the Japanese allowed Orth to write postcards home. Examined by censors of both Japan and the United States, the sentences on these cards did not have the easy flow and style of Orth’s earlier letters home indicating that the writing was contrived by his captors for maximum propaganda value. In one card he wrote, “I am always wishing that this miserable war would be over and that I should return home again. The Japanese treat us well, so don’t worry about me, and never feel uneasy.” In a second card, Orth penned, “It will be wonderful when we meet again. Good bye. God bless you. I am waiting for your reply earnestly.” Both cards were signed uncharacteristically, “Eugene.” In a third note, Orth signed his usual “Buster” but numbered each sentence in a nonconsecutive manner as if copying them from examples provided him by his captors. He wrote glowingly of his conditions,

By 1945, the cards’ tone had changed to read much more like Orth’s normal phrasing. In a final card written just before his release he wrote, “Another card just to let you know that everything is alright and still in good health. . . . Looking forward to being with you. In the meanwhile all the best and all my love. Buster”

Because of their medical training, Orth and Australian Reg Withers were assigned as the camp’s undertakers at St. Vincentins. This duty gave them access to the dead men’s clothes and possessions, which they distributed to the living. Orth remembered in 1952, “With the exception of the few medical supplies the Dutch Army managed to retain, medical supplies and equipment were inadequate to nonexistent. Medical facilities were from nonexistent to poor depending on camps.”

Orth’s next prison camp was Bandung, located in the inland mountains, southeast of Batavia and almost directly south of Cheribon. This was the worst camp of all, according to Orth. In 1952 he observed, “Living conditions were poor to appalling, while facilities at best were always overcrowded. At no time was bedding ever furnished.” About 2,500 POWs were interned in a place big enough to hold two hundred. Men had no beds and slept on the stone floor when there was room to lie down. Sanitary conditions were terrible, and dysentery was rampant. Orth became extremely thin and nearly died in Bandung.

Orth was at Bandung from December 1944 until the war ended in August 1945. On 17 September 1945, U.S. authorities moved him from Bandung to Batavia and on to Singapore, arriving at 3:30 P.M. local time. Vadm. Louis Denfield, the Chief of Naval Personnel wired Ednah Orth, “I am pleased to inform you of the liberation from Japanese custody of your son Eugene Orth Pharmacist’s Mate Second Class USN. His condition is reported as good. You are invited to send him free via this bureau a twenty-five-word message. . . . I rejoice with you in this good news.”

After a two-thousand-mile flight from Singapore to Calcutta, Eugene Orth returned to the “jurisdiction of the U.S. Navy following [his] prisoner of war status” at 2:00 A.M. on 18 September 1945. On 1 October, Colonel Rugheimer, Commander of Replacement Depot Number 3, ordered him to proceed by air transportation to any U.S. airport for further assignment. Orth was allowed sixty-five pounds of baggage for the journey, all of which must have been newly purchased or issued after his losing all of his possessions with Houston and enduring forty-five months as a POW. The North African Division of the U.S. Army Air Corps’ Air Transport Command, under the command of Brig. Gen. James S. Stowell, provided Orth C-54-D aircraft transportation on its “Rocket Run” service between India and northwest Africa and on to the United States. The homeward journey from Calcutta began 2 October at 3:15 P.M. Stops along the way included Agra, Karachi, Abadan, Cairo, Tripoli, Casablanca, the Azores, and Newfoundland. The over sixty-eight-hour, thirteen-thousand-eight-hundred-mile trip ended at 11:45 A.M. on 6 October when Orth’s airplane landed at New York’s LaGuardia Airport. He had completed a six-and-one-half-year, around-the-world odyssey begun in May 1939 in Norfolk aboard USS Henderson.

The newspapers made no mention Orth’s return to the United States. Little wonder, since his arrival in New York was hardly news of importance to anyone but loved ones waiting for him in Vermont. Thousands of veterans returned each day aboard heavily laden ships whose arrival times in New York, Boston, San Francisco, and other ports were duly reported by the press in announcement columns set apart from the day’s news. New York especially welcomed servicemen with complimentary stage play and movie seats, no-cover-charge nightclub opportunities, and free museum passes. What returning veterans sought, however, was contact with home.

Orth telephoned Vermont to announce his return just as soon as he could find an available and working telephone. In early October 1945, the Long Lines Department of the telephone company was the victim of a labor strike, which had disrupted regular long distance service; however, preference was given to returning servicemen at St. Albans Naval Hospital, Halloran Hospital, Camp Shanks, and Pier 92 where the men disembarked. Since the Navy assigned Orth as a patient to Ward 113 in St. Albans Naval Hospital on Long Island, he got a call through to family with relative ease.

At St. Albans he received a complete physical checkup and he rested and recuperated before heading home to Vermont for convalescence leave. There he received congratulatory mail from friends, relatives, a long-time sweetheart, and an official letter from Pres. Harry S. Truman. “You have fought valiantly and have suffered greatly,” wrote the President. He noted with pride Orth’s “past achievements and express[ed] the thanks of a grateful Nation for [his] services in combat and [his] steadfastness while a prisoner of war.”

His future also occupied him during his time in the hospital. While he visited his sister Peg in Lowell, Massachusetts on a furlough from St. Albans, Orth took a side trip to Bellows Falls to become reacquainted with his high school sweetheart, Ellen Griffin, still living there. In mid-October he proposed marriage to her and she accepted. On 23 October, Orth wrote Ellen from his sister’s house in Massachusetts, “You can sue me now for putting it in writing, but I still do love you. . . . I was so dammed lonesome the first nite [sic] here that I almost decided to return.” She wrote him back the next day after receiving his letter, “Will have time only to tell you how much I love you, and miss you too.” The local newspaper published their engagement announcement on 25 October, and Eugene Orth married his sweetheart on 6 January 1946, eleven years after he had left her and Bellows Falls for U.S. Navy duty. In February, after a honeymoon in New York City and Washington, DC and his convalescence leave completed, Orth was discharged from St. Albans Naval Hospital, and he reported for duty as the Property and Accounting Officer at the Naval Dispensary, U.S. Naval Shipyard, Portsmouth, New Hampshire to continue his Navy career.

Orth’s Navy rate was changed 20 May and again on 10 July to account for the period of time he was in a POW status. While he was promoted to Chief Pharmacist’s Mate (effective 2 September 1943), Pharmacist (effective 1 October 1943), and Chief Pharmacist, W-1 (temporary Warrant Officer rank effective 1 January 1945) retroactively, no retroactive increases in pay and allowances were allowed by the government. Furthermore, his temporary Chief Pharmacist, W-1 rank could be voided by the Navy at any time.

In August, desiring to solidify his future in the Navy, Orth applied for augmentation into its Regular component as a permanent, commissioned Warrant Officer. The post-war Navy was reducing its force structure significantly and opportunities for Navy Reservists to transfer into the Regular Navy were rare. Still, Orth’s service record was spotless and contained perfect ratings for proficiency and conduct; he had been officially written to by the President; and he had proven himself a courageous warrior by spending over one quarter of his active duty service time as a prisoner of war, enduring for years horrible conditions on behalf of the Nation.

The Navy denied his application for augmentation into its Regular forces. On 22 November 1946, Vadm. Louis Denfield, Chief of Naval Personnel, wrote to a disappointed Orth,

“The number of applications from officers who desire to transfer to the regular Navy as commissioned warrant or warrant officers has been far in excess of the numbers required to meet the needs of the Navy. . . . I regret to inform you that your name was not included in the recommendations of the Selection Board for appointment. The decision in your case . . . was made only after a careful review of your record . . . as compared to other officers who requested transfer to the regular Navy. The interest you have shown in pursuing a naval career represents an exemplary attitude of service and patriotism.”

His planned Navy career was beginning to unravel.

About Thanksgiving of 1947, Orth, now stationed at the Naval Hospital, Portsmouth, New Hampshire received a letter from Radm. C. A. Swanson, Chief of the Navy’s Bureau of Medicine and Surgery that brought more bad news to his career plans. “Recently enacted budgetary limitations impose a personnel reduction on the Navy Department,” wrote Rear Admiral Swanson, “and precludes the possibility of your retention on active duty in your temporary officer status.” In twenty-first-century-speak, the Navy had downsized the former POW. Orth received orders from the Secretary of the Navy in early December 1947 terminating his “temporary appointment as a Chief Pharmacist for temporary service” shortly after his attending the 10 December Semi-formal Portsmouth Naval Base Christmas Party Dance.>

On 17 August 1949, the Navy transferred Orth (accompanied by his wife and two-year-old son) to the U.S. Naval Air Station, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. Three months later, he moved to the U.S. Naval Hospital on the base. Orth’s son, Tom, writing an essay for a St. Josephs’ Catholic School (on East Simpson Street, Mechanicsburg) assignment when he was a young teenager remembered his and his mother’s trip to Cuba, “I recall very little of this trip only that we were both air sick for most of the journey. . . I was very hot there and I do remember having Christmas dinner out doors.” On the trip back to the United States when Orth’s tour of duty was completed, young Tom wrote for his teacher, “We came back by ship on the U. S. S. Gothels. It was a big ocean liner and I recall the good food we had on board. Our destination was Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania to the Naval Supply DepotTom’s writing effort received a grade of B+.

In 1948 Congress passed the War Claims Act (Public Law 80-896), which created a War Claims Commission (WCC), later called the Foreign Claims Settlement Commission, to adjudicate claims and pay out small lump-sum compensation payments to military POWs from a War Claims Fund. The fund consisted of Axis assets seized and liquidated under the Trading with the Enemy Act of 6 October 1917. Under Section 6 (b) of the War Claims Act, payments to prisoners of all theaters of the war that were deprived adequate food rations in violation of the Geneva Convention of 27 July 1929 were to be at a rate of $1.00 per day of imprisonment. In 1952 the act was amended with a new Section 6 (d) that included an additional payment of $1.50 per day if a POW could prove that he was subjected to inhumane treatment or forced to perform hard labor in violation of the Geneva Convention. Therefore, the maximum a POW could receive was $2.50 per day of captivity.

On 5 April 1950, the WCC acknowledged Orth’s application for the $1.00 inadequate food compensation payment for his 1,298 days’ imprisonment and assigned him claim number 025149, and on 7 September 1952, the WCC acknowledged his updated application requesting an additional $1.50 per day of captivity for his being subjected to inhumane treatment and forced to perform hard labor. He noted on his application, “most labor performed . . . was carried out in swampy, malarial mosquito infested areas. No protection whatsoever was provided against this constant menace.” The WCC subsequently approved both of Orth’s requests and awarded him $3,245, the maximum allowed $2.50 per day for his three and one-half years of torture, abuse, deprivation, and disease. In 2005 dollars, this amount represented over $23,000.

Orth commanded the Medical Clinic at the U.S. Naval Supply Depot, Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania before retiring to the private life and civilian employment. He left active duty and transferred to the Navy’s Fleet Reserve on 20 August 1954, and was ordered to “keep yourself in readiness to respond to orders to active duty in time of war or national emergency.” In preparing for a civilian career, he obtained real estate sales and life insurance salesman licenses for Pennsylvania. He joined the Mechanicsburg Memorial, Post Number 6704 of the Veterans of Foreign Wars, the Enola American Legion, and Fleet Reserve Association of Washington, DC. After over thirty years’ faithful service, Orth retired from the Navy as a Chief Warrant Officer, W-2 on 26 March 1965, a sailor in the armed forces of his country for well over half his life. He died thirteen months later.

****************************************************************************************************

Scuba divers sanctioned by the Republic of Indonesia found the battered hulk of Houston in July 1973, almost thirty-one and one-half years after she went to the bottom of the Sunda Straight. They recovered several items from the wreck, including a telescope, a ring, a Lewis machine gun, a USS Houston book, and laundry identification stamps of Donald G. Stower and Edward T. Carlyle, both men lost with the ship in 1942. In a solemn ceremony, the Indonesian government presented the raised five-hundred pound ship’s bell to U.S. Amb. Francis J. Galbraith, who sent it as an honor to her crew’s service and sacrifice to be exhibited on the retired battleship USS Texas, berthed at the San Jacinto Battleground at Houston, Texas. Halfway around the world from “The Ghost of the Java Coast,” which is still manned by over seven hundred of his shipmates, Eugene Orth could no longer enjoy the recognition: Fair winds and a following sea, sailor.