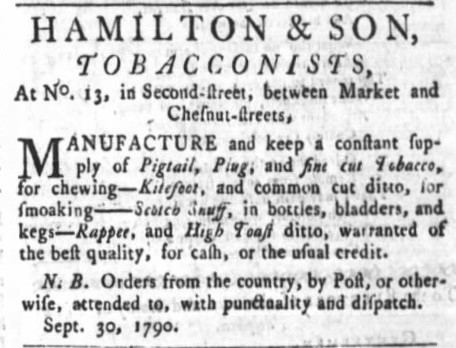

Settlers in colonial America adopted the use of tobacco after it was introduced to them by native peoples in the 1600s. Tobacco plantations proliferated as the demand for tobacco grew. After tobacco was harvested, it had to be cured. Tobacco leaves were hung in barns and fire-cured, a process that took several days to several weeks. Depending on how tobacco leaves were pressed, tobacco could be smoked in a pipe, chewed, or used as snuff. Tobacco was sold by the pigtail (twist), the plug, fine cut for chewing, common cut for smoking, and as snuff. Customers could buy their tobacco from shopkeepers or from tobacco manufacturers.

Tobacconist David Allen and his wife Sarah came to Carlisle in 1777 from Londonderry Township, Lancaster County.1 David purchased Lot #52 on West High Street2 and for the next fifteen years he carried on a tobacco manufactory. The inventory taken at the time of David’s death listed the following items related to his business: one snuff mill and stones “not set up,” one old press screw, one tobacco wheel and table, two tobacco presses “set up” and crowbar, six rolls of tobacco, leaf tobacco estimated at 4 hogsheads, valued at £50, and a large bundle of tobacco cards.

David wrote his will three months before his death on November 10, 1792. He left his wife Sarah the house and lot as well as the furniture and movables. He directed that his mother, who had been living with them in Carlisle, should be given £22 annually for her maintenance. He willed his plantation in Londonderry, Dauphin County (previously Lancaster County) to his brother Joseph Allen along with £70. He willed £5 to his brother John Allen and £25 to his brother James Allen. To James’ four children he willed the following: £25 to James, his plantation in Northumberland County near Montour’s Hill to William, to Robert, the eldest son of James, one guinea, and to David his gun and shot pouch as well as two Volumes of Askin’s Works, upon Sarah’s decease.3

After Allen’s death in 1792, his widow Sarah advertised that the tobacco business would be carried on as usual.4 She became sick two years later and died after a short illness on February 28, 1794. She was 56 years old.

Sarah wrote her will one week before her death. She stipulated that she was to be buried near her husband David and marble stones put on their graves with the dates of their death and their ages.

Because she and her husband were childless, she left her possessions to her relatives. She left her nephew, David Craig, the western half of her Carlisle lot when he arrived at age of 215 and £50 for his use during his apprenticeship. She willed the eastern half of her Carlisle lot to her nephew Allen Watson when he reached 21 years of age.6 She left her brother John Craig £30 and a third of her library. (Sarah’s executors inserted a notice in the newspaper stating that “If John Craig, brother of the late Sarah Allen of the Borough of Carlisle, who it is said lived near Pittsburgh, will apply to the executors of the said deceased, he may hear something to his advantage.”7)

To her sister Mary Sloan’s children, George, Isabella, Sarah, and Rosanna, she willed £50 each if they gave up all rights to their grandfather John Craig’s estate, now in possession of William Wilson of Hanover Township, Dauphin County (previously Lancaster County). The girls each got one third of her wearing apparel, table linen, and a third part of her library which they had to share with their brother George. She left her sister Watson the half remainder of her estate, one third of her wearing apparel, table linen and library. To her brother John’s children, by his present wife, she left the whole of the remainder of her estate to be equally divided amongst them; only that the oldest son William was to have two shares. Also, to her brother John’s wife and daughters, a third part of her wearing apparel and table linen.8

The inventory of Sarah’s estate mentioned “the red house” as well as contents in her house, and also the contents of “Miss Polly Craig’s room.” The more than two dozen books in her library were almost entirely on religious topics. She had a large wardrobe, and her wearing apparel accounted for almost one-quarter of the value of the estate.

The following items related to the tobacco business were in the cellar under the south room at the time her inventory was taken: one tobacco wheel valued at 7shillings 6 pence, one snuff mill and pair of stones £2, timber for a tobacco press 10 shillings, one lying press and box at £5, one tobacco table valued at 2 shillings, 6 pence, 67 rolls coarse and fine tobacco worth £53, 7 shillings 1 pence, and two tobacco presses in the front house cellar at £5 each. Sarah’s executors sold her furniture and three tobacco presses at an auction a month after her death.9

James Spottswood, who had been running the Allen’s tobacco business for several years before their deaths, informed their customers that he would continue the business as usual at their house.10