Forty-seven-year-old Irishman, Richard Dougherty, arrived in Carlisle in 1800 with his family.[1] He placed an advertisement in Kline’s Carlisle Gazette announcing his plan to open an English school.[2] He would run that school successfully for more than 20 years.

In the January 1, 1813 edition of Kline’s Carlisle Gazette, Dougherty thanked the citizens of Carlisle “for the very liberal encouragement given him these twelve years past” and that he has “at very considerable expense, erected and completed a commodious and comfortable school room where he continues to teach the usual Reading, Writing, Vulgar and Decimal Arithmetic, Mensuration, Book Keeping and English Grammar, classically. He proposes a monthly examination where the parents, guardians, etc. are requested to hear testimony of the different gradations of improvements made by his pupils.”

His 1814 advertisement included the cost of tuition for his school, viz: “two and a half dollars per Quarter, three dollars for those entered by the day or month, and five dollars per Quarter for instruction in English Grammar. NB. He will rent from the first day of April next, the lower part of the house he now occupies which is commodiously adapted for a store and a small family, in an agreeable and much frequented part of town.” [3]

In his reminiscences of Carlisle in the 1820s and 1830s, James Miller McKim remembered Dougherty’s school. He wrote that the school:

“…stood in a dingy house of yellowish stone, which served the purpose upstairs of a seminary of learning and downstairs of a cake shop. Master Dougherty presided above and Mistress Dougherty below. Buying our horse-cake at the counter, and passing over to the pump opposite to eat it, we could hear from the open windows, all that was going on in the school room. “Now, the reading class! Take your places. Less noise in that corner! Begin, (the master himself taking the initiative in a sonorous staccato.) “Hold—up—your head.” Then the boys, in a chorus still louder: ‘HOLD UP YOUR HEAD.” Then the boys suiting the action to the word: “Speak loud and plain.” Then the boys suiting the action, still more emphatically to the word ‘SPEAK LOUD AND PLAIN, etc., etc.” [4]

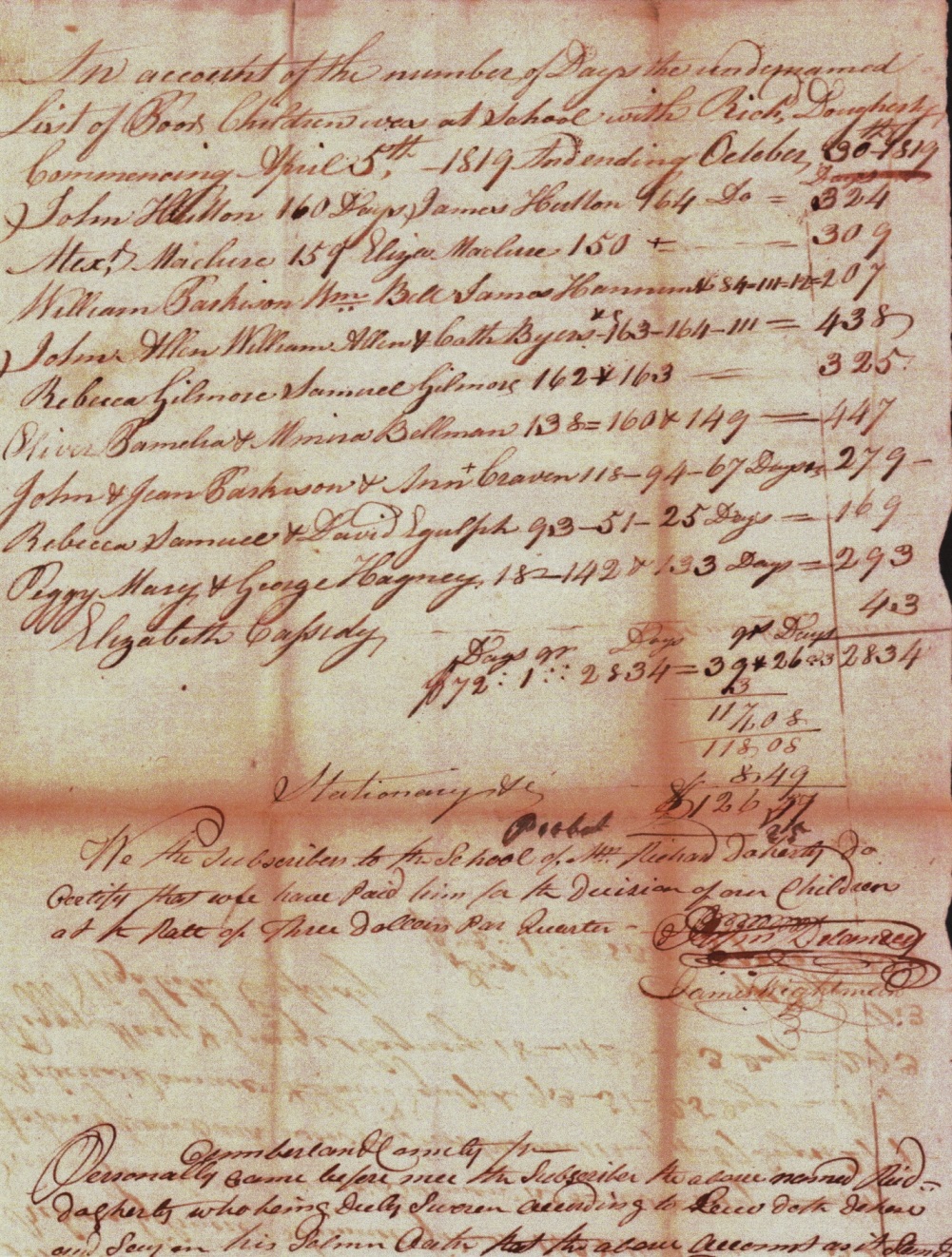

Dougherty was one of several teachers in Carlisle who taught “poor children.” Before the creation of the Common school system in 1836, education was not free. Children were schooled at home or their parents paid tuition to a schoolmaster to teach their children. In 1809, “An act to provide for the education of the poor, gratis…” was passed by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Tax assessors for each municipality were required to receive the names of children between the ages of five and twelve whose parents were unable to pay for their schooling. The parents were then at liberty to send the children to the school most convenient to them, and the expense for their schooling would be paid by the county. The schoolmaster was required to keep a day book listing each “pauper child” with the number of days he taught them, and the amount of stationery used for them. He submitted his invoice for approval to three trustees or subscribers of the school who vouched for the invoice, and then the school master submitted the invoice to the County Commissioners for payment.

Dougherty gave up teaching in 1821 and applied for a license to keep a tavern. He was licensed for at least two years. When his son, Edward, advertised his chair making business in 1823, he said that it was located in the Main Street, directly in the rear of his father’s inn called the “Sign of General Washington.”[5]

On January 28, 1828, Dougherty granted his house and lot to his sons Edward and James for one dollar, because, he said, they gave him money for his maintenance.[6] Dougherty had purchased the property (Lot #277) at a sheriff sale in 1808 for $195.[7] The log house that had previously stood there had been replaced by a two story stone house. Richard Dougherty was still living there in 1830 when he advertised that the house was available for rent. The property included three rooms and a kitchen on the first floor, a good cellar underneath, and on second floor five comfortable rooms. The property also had a large yard and an excellent garden.[8]

On October 24, 1836, while confined to his sick bed, Dougherty made his will. He left his property to his wife and sons Edward and James.[9] His obituary stated that he died on October 28, 1836, aged about 83 years. “He was a native of Ireland, but for more than 30 years a respected inhabitant of this borough.”[10]