Shortly before 1840, John Cassilus Neff1 and his family settled in Carlisle where he opened his practice as a dentist.2 During the 1840s, Dr. Neff would read newspaper articles about the great wagon train migrations to the west, the annexation of Texas and the battles of the Mexican War, but his life would change when he read that gold had been discovered at Sutter’s Mill in California on January 24, 1848.

News of the gold strike reached the newspapers in the east in August 1848. Four months later, Dr. Neff bid his wife and three children farewell3 and left for California with a party of local men. They traveled to California by way of Cape Horn.4 The 15,000-mile trip took from three to six months. The trip was dangerous, especially sailing in the frigid, treacherous waters around the tip of the Cape.

An alternate trip to California by ship was cheaper and shorter, but you had to cross the jungles of Panama with its poisonous snakes, swarms of insects, malaria and cholera. The overland route could be as brutal in a different way.

In November 1849, the Carlisle Herald announced “that intelligence has been received, by the last steamer, of the safe arrival in California of Dr. J. C. Neff, who left Carlisle last winter and took passage by sea….”5

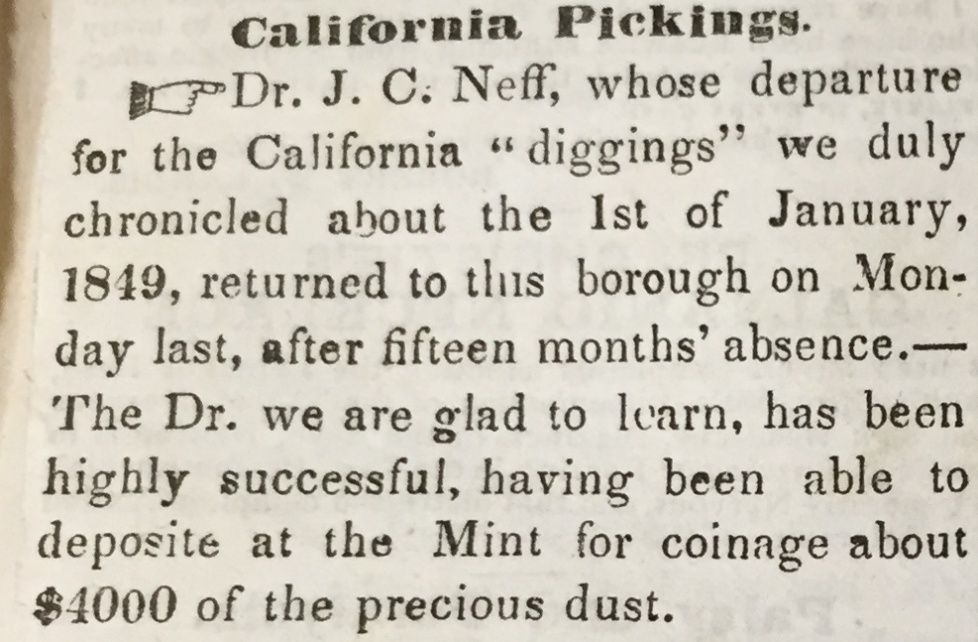

Unlike many men who went to the gold fields, not only did Dr. Neff return home, but he actually found gold. “California Pickings,” headlined an item in the April 1, 1850 edition of the Carlisle Herald. “Dr. J. C. Neff,” the newspaper reported, “whose departure for the California “diggings” we duly chronicled about the 1st of January 1849, returned to this borough on Monday last, after a fifteen months’ absence. The Dr., we are glad to learn, has been highly successful, having been able to deposit at the Mint for coinage about $4,000 of the precious dust.”

Dr. Neff “saw the elephant,” as the expression of the day went, and he had his big adventure. Once back in Carlisle, he spent the remainder of his life tending to the dental needs of the town’s residents from his house on West High Street.6 He died at his residence on Sunday, June 1, 1884. He had been in failing health for some time, and a stroke killed him almost immediately.7 He is buried in Ashland Cemetery with his wife and several children.