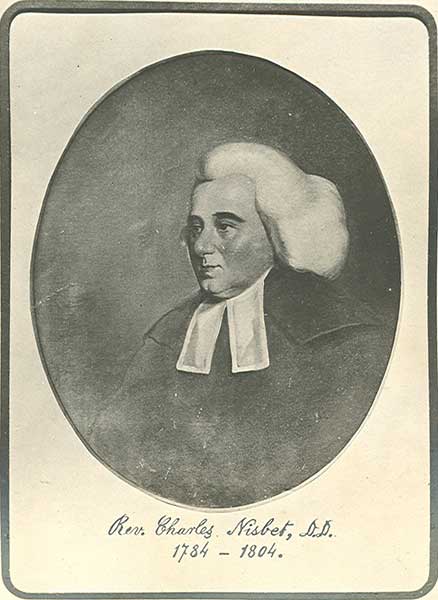

Charles Nisbet (21 January, 1736-18 January, 1804), was born near Haddington, Scotland, and died in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Educated at the University of Edinburgh, he was a Presbyterian minister and formidable scholar, known to contemporaries as a walking library. From 1785 to 1804 he served as the first principal (president) of Dickinson College.1

Nisbet’s tenure at Dickinson began at the invitation of Benjamin Rush, who had founded the college and named it for his colleague, John Dickinson. Rush had met Nisbet in Scotland when Rush was studying medicine at the University of Edinburgh. In Scotland, Nisbet had been friends with John Witherspoon, also a Presbyterian minister, and Rush had persuaded Witherspoon to come to America to serve as president of the College of New Jersey, now Princeton.

Witherspoon (1723-1794) was at first reluctant to accept the position, recommending Nisbet instead. Eventually Witherspoon relented, and once in New Jersey, he became a delegate to the Continental Congress and a signer of the Declaration of Independence. In 1783 he had his new college award Nisbet, in absentia, an honorary doctorate of divinity. Rush’s idea was to secure for the new college in Carlisle a scholar comparable to Witherspoon and with similar political sympathies.2

In Scotland, Nisbet had been an admirer of the American colonists’ paradoxical claims for independence from the Crown to protect their rights as British subjects. Once in the United States, however, Nisbet soon became disillusioned. From almost his first day ashore, Nisbet regretted having brought himself and his wife and their four children to America. Constant arrearages in his salary kept him from saving enough money to return to Scotland. Nisbet’s correspondence is full of complaints, often witty but caustic, about Carlisle, the college, and the country.

In 1794, residents of Carlisle supported the Whiskey Rebellion that had begun in western Pennsylvania. President George Washington came to Carlisle to review the troops assembling to march westward and put down the rebellion. At the Presbyterian Church on the town square, Nisbet preached a controversial sermon on 1 Thessalonians 4:11, his interpretation being that people needed to know their place in society. Informing Nisbet’s fears for the survival of a rightly ordered society was the horror he felt as he read reports of the violent upheavals caused by the French Revolution.3

Nevertheless, Nisbet slogged on at his duties at Dickinson. Year after year, in addition to lecturing on Protestant theology, he taught a course on European literature, and the substance of what he taught survives transcribed in the notebooks of his students. Nisbet’s course, “Lectures on Criticism,” has recently been made available on-line.4

All the while, Nisbet held a dim view of the intellectual capacity of most of the college’s trustees and their ability to promote culture and Christianity in frontier America.5 He held out more hope for some of his students. Still, Nisbet did not live to see one of his students, his son, Alexander, become a judge in Baltimore, and another student become prominent in national politics, Roger Brooke Taney serving the country as Attorney General and then as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court.

While deploring the backward conditions of life in a small town in the new Republic, Nisbet sought to maintain certain comforts of British domestic life, such as importing his own tea. He also ordered books and newspapers from a bookseller in Philadelphia, and one news item in particular summed up for Nisbet the barbaric anarchy of his adopted country: a young woman in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, acquitted for having laced her mother’s tea with arsenic.6

Portly for many years and irascible to the end, Nisbet died of pneumonia in the winter of 1804. He was buried in the Old Graveyard, the town cemetery, in Carlisle, his marble monument inscribed with a lengthy Latin epitaph.7